PACE trial

This article needs cleanup to meet MEpedia's guidelines. The reason given is: Too long. Please consider splitting content into other articles, or condensing it (2022) |

The PACE Trial study (short for "Pacing, graded Activity, and Cognitive behaviour therapy; a randomised Evaluation") was a large and controversial trial of treatments for people with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS), also known as Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME).[1]

The PACE trial compared standardised specialist medical care (SMC) alone to SMC plus Adaptive Pacing Therapy (APT), Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), or Graded Exercise Therapy (GET). The researchers that conducted the trial expected that the CBT and GET groups would see the greatest improvement,[1] and this finding was reported in subsequent articles published by them.[2][3][4] This claim has been controversial, however, due to patient groups finding that exercise made patients deteriorate and CBT lacked benefit, and concerns regarding the methodology and refusal to release the full data.[5][6][7] Some patients campaigned for the full release of the PACE study's results, and after a five year battle, the PACE trial data was released for others to analyse.[8] The full PACE data led to over 40 scientists writing an open letter to the Lancet to raise serious concerns about the study, and asking for a new, independent analysis of results.[7]

The PACE trial has been highly influential in clinical guidelines in the UK, and other countries, in both government funded health care and private medical insurance, and had a significant influence on the Cochrane reviews for ME/CFS treatments.[9][10][11] By the time the main PACE trial results were published, the UK had included CBT and GET in clinical guidance for four years - the PACE trial was expected to confirm that they were effective.[9]

Background

The PACE trial[2] was funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Department of Health and Social Care (UK) for England, Scottish Chief Scientist Office, and - apparently uniquely for a clinical trial - the Department for Work and Pensions - the government department for sickness, disability and pension benefits. The PACE trial cost £5 million[12] and is the most expensive piece of research into ME/CFS ever conducted.

Recruitment of patients began in March 2005 and data collection was completed in January 2010.[2] The study protocol was published in BMC Neurology in 2007.[13] The main study outcomes were published in The Lancet in 2011[2] and the experimenters continued to publish papers on the PACE trial for a number of years.

The principal investigators were Professors Peter White, Trudie Chalder, and Michael Sharpe. Although not an author, Professor Simon Wessely provided feedback on their report.[2] He stated in November 2015 that "there are also more trials in the pipeline".[14]

Study design

641 patients were randomised into four groups in the study.[2] All received specialist medical care (SMC), which consisted of medication for symptoms such as insomnia and pain, and general advice to avoid extremes of rest and inactivity.[15] One group received SMC alone. Patients in another group additionally received adaptive pacing therapy (APT), and were advised to stay within the limits of activity imposed by the disease to give their bodies the best chance of recovery.[16] The other two groups were both told that they were not ill but deconditioned, and that if they gradually increased their activity, there was nothing to prevent their recovery.[17][18] The cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) group focused on addressing their presumed fear of activity while the graded exercise therapy (GET) group focused on increasing their activity in a structured manner, with regular aerobic exercise as the eventual goal.

Patients in the APT, CBT and GET groups were offered up to 14 sessions with a therapist over a six-month period, to support them in following their therapy programmes, with a top-up session at 36 weeks. They also received a lengthy manual[16][17][18] explaining their therapy. All participants were offered at least three sessions of SMC.

Patients were assessed at baseline, 12 weeks, 24 weeks and 52 weeks. The main outcome measures were self-rated fatigue and physical function. Secondary measures included the study's objective variables such as a six-minute walking test, a fitness test and economic measures including the number of days of work lost due to fatigue, and the receipt of sickness benefits.[13]

Patients were also followed up (using subjective ratings only) at least two years after randomisation.[4]

As of May 7, 2018, the PACE manuals were not retrievable from the QMUL website, but they were retrievable as of 16 July 2022.[19]

All documents pertaining to the PACE trial can be found following the link PACE trial documents.

Findings

The trial's results showed that patients in the CBT and GET groups improved more in self-rated fatigue and physical function than the APT or SMC-only groups.[2] Apart from the GET group improving slightly more than the others on the six-minute walking test,[2] all of the study's objective measures[20][21] and the long-term follow-up data[4] (self-ratings of fatigue and physical function) showed no difference between groups.

The authors reported, in a 2013 paper specifically about recovery, that 22% of patients in the CBT and GET groups had recovered following these therapies, compared to 8% in the APT group and 7% in the SMC-only group.

Impact

The PACE trial and other studies that use the Oxford criteria for diagnosis of ME/CFS have had a major international impact on popular perceptions of the disease and on public policies on treating and researching it.

Media

On February 27, 2011, when the first PACE trial paper was published, researchers Michael Sharpe and Trudie Chalder held a press conference[22][23][24] to discuss their findings. Chalder stated, "twice as many people on graded exercise therapy and cognitive behaviour therapy got back to normal."[25] That assertion has been criticized for grossly overstating the study's actual findings.[26][27][28]

The claims made about the study were covered in the UK and international press.[29][30][31][32][33] For example, The Daily Mail stated, "Fatigued patients who go out and exercise have best hope of recovery",[34] while The New York Times declared "Psychotherapy Eases Chronic Fatigue Syndrome".[35] According to the British Medical Journal's report on the trial, some participants were "cured."[26]

Many other PACE papers followed, although with relatively little media attention until October 2015, when long-term follow-up results were published in The Lancet Psychiatry.[4][36][37][38][39][40][41] The Daily Telegraph ran a front-page story with the headline, "Exercise and positivity can overcome ME."[42][43] The piece stated, "Chronic Fatigue Syndrome is not actually a chronic illness and sufferers can overcome symptoms by increasing exercise and thinking positively, Oxford University has found". The article quoted Professor Sharpe describing ME as a "self-fulfilling prophesy" that happens when patients live within their limits. The article was altered following public pressure but no formal retraction was made. Science Magazine also published an article in October 2015 along with comments from Sharpe about the growing criticism outwith the patient community from the broader science community.[44]

In the UK the Science Media Centre is a government-funded body that describes its purpose as being to improve science journalism. Its reporting on ME/CFS has been criticized for bias towards a psychological etiology for the disease.[45]

Influence on treatment

The large size of the PACE trial has meant that it has had a substantial impact on the evidence base in ME/CFS. Together with other studies of CBT and GET, it is highly influential in UK clinical policy and that of many other countries, both in terms of healthcare provided by government[9] and by private medical insurance.[10][11] The influential Cochrane exercise therapy review relied significantly on the PACE trial.[46]

In the UK, the NICE guidelines for National Health Service (NHS) provided care[9] recommend CBT and GET for ME/CFS. They were published in 2007, before the PACE trial was conducted, but the evidence was based on a few small trials and was considered "somewhat limited".[47] The ME Association has asked for the guidelines to be updated to take into account new treatment evidence, noting, "we assume that the guideline surveillance review that took place in March 2011, and which followed publication of the PACE trial in February 2011, simply ‘rubber stamped’ the 2007 NICE guideline recommendations on the basis that the PACE trial had supported the recommendations relating to CBT and GET."[48] NICE responded, "we still do not feel that the evidence base is substantially evolving in this area at this time".[49] After considerable objections, this decision was reversed and the NICE guidelines clinical review began in 2017.[50]

In the US, the Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, Kaiser Permanente, and numerous key secondary medical education providers, such as UpToDate and WebMD, recommend CBT and GET, using PACE as a reference. CBT and GET were included in the Center for Disease Control's clinical guidelines for CFS, based on the PACE trial evidence.[51]

Criticisms of the study

Selection of patients

The PACE trial used the Oxford criteria for diagnosis. Many patients and specialist clinicians consider them overly broad,[52][53] and the National Institutes of Health 2015 P2P report[54] on ME/CFS recommended that the Oxford definition be retired for this reason.

Changes in criteria for effectiveness and recovery

Image: Senseaboutscienceusa.org

The authors abandoned their protocol-specified main outcome and recovery analyses partway through the trial and replaced them with others.[2][3] They have defended the changes, noting, "All these changes were made before any outcome data were analyzed (i.e. they were pre-specified), and were all approved by the independent PACE Trial Steering Committee and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee."[55] However, 42 scientists, in an open letter to the Lancet, stated that the changes were of "of particular concern in an unblinded trial like PACE, in which outcome trends are often apparent long before outcome data are seen. The investigators provided no sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of the changes and have refused requests to provide the results per the methods outlined in their protocol."[56]

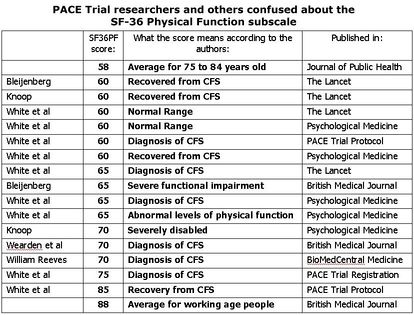

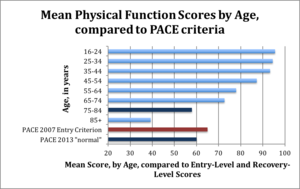

Most notably, the authors introduced post-hoc "normal ranges" for fatigue and physical function.[2] These ranges have been heavily criticised for having thresholds so low that patients could worsen from trial entry and yet be within these normal ranges. The "normal range" for physical function (measured on the SF-36 100-point scale) was 60 and above, even though patients had to score 65 or lower to enter the trial. A score of 60 is close to the mean physical function score (57) of patients with Class II coronary heart failure.[57]

"The average age of participants in the PACE trial is about 39 years old; normative data suggest that people in this age group should have SF-36 scores of about 93. Yet the new 2013 “normal” is a score of 60."[58]

The PACE authors used the "normal ranges", in conjunction with other thresholds, to define clinical effectiveness in the Lancet[59] paper and recovery rates in a later paper in the Journal of Psychological Medicine.[60]

All Freedom of Information requests to the authors for the main outcome and recovery results according to the protocol-specified analyses, or for the underlying data so that others could conduct the analyses, have been refused.[61][62][63][64]

Use of subjective main outcome measures

The study has been criticised for having subjective primary analyses in an unblinded trial.[65] Subjective measures are known to be susceptible to bias, as can arise from expectations and social pressure. The CBT and GET groups, but not the others, were told that there was nothing to stop them from recovering if they gradually increased their activity, and critics have argued that these differential expectations could have inflated their self-assessments.[7][66]

Conflicts of interest and lack of informed consent

The forty-two scientists and clinicians who wrote an open letter to the Lancet complaining about the PACE trial criticized the study authors' failure to disclose a potential conflict of interest to trial participants.[56] They wrote:

"The investigators violated their promise in the PACE protocol to adhere to the Declaration of Helsinki, which mandates that prospective participants be 'adequately informed' about researchers’ “possible conflicts of interest.” The main investigators have had financial and consulting relationships with disability insurance companies, advising them that rehabilitative therapies like those tested in PACE could help ME/CFS claimants get off benefits and back to work. They disclosed these insurance industry links in The Lancet but did not inform trial participants, contrary to their protocol commitment. This serious ethical breach raises concerns about whether the consent obtained from the 641 trial participants is legitimate."

Newsletter to participants

The investigators published newsletters for participants[67][68][69][70] while the trial was still underway. Critics have said that the material in the third newsletter[69] could have influenced patients' self-reported outcomes. It included a number of positive testimonials from patients in the trial, but without naming their therapies. The PACE authors have argued that this meant that there would be no bias in favour of CBT and GET[55] but Professor James Coyne has dismissed the idea that bias would be expected to affect all four groups equally.[71]

The newsletter did, however, announce that the new NICE guidelines, "based on the best available evidence... recommended therapies [that] include Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, Graded Exercise Therapy and Activity Management." There was no explanation of what "Activity Management" was: no group had that title in the PACE trial. Dr. Bruce Levin, a professor of biostatistics at Columbia University and an expert in clinical trial design, said, "To let participants know that interventions have been selected by a government committee 'based on the best available evidence' strikes me as the height of clinical trial amateurism".[26] The newsletter also contained a less than positive assessment of research on the possibility of an infectious component of ME/CFS, including research by Jose Montoya on herpesviruses and by John Chia on enteroviruses. The newsletter said of Dr Chia's work, for example, "The laboratory work looked convincing, but many patients had significant gastro-intestinal symptoms and even signs, casting some doubt on the diagnoses of CFS being the correct or sole diagnosis in these patients." It is possible that this negative view of evidence of an ongoing infection would have made the rationale for APT appear less plausible and that for CBT and GET more plausible, thus biasing the participants.

An account of another study, in contrast, gave a positive assessment of CBT, saying "cognitive behaviour therapy was associated with an increase in grey matter of the brain and this increase was associated with improved cognitive function".

Risks and side effects

A survey[6] conducted by the ME Association in 2012 showed that 74% of patients had their symptoms worsen after a course of GET. In contrast, the PACE trial found no apparently meaningful difference in rates of adverse events between the four trial groups,[72] suggesting that APT, CBT and GET added no risk to SMC alone (since all four groups received SMC). However, critics have questioned whether patients actually increased their activity sufficiently in the CBT and GET groups to trigger many serious adverse events:[73][74] the lack of improvement in the step-fitness test in all groups indicates that this is distinctly possible.[21]

Analysis by "citizen-scientists" - ME Sufferers and Charities

Numerous ME sufferers and other interested parties have produced critiques of the PACE trial including statistical analyses and trial methodology.

Mr Courtney has written a number of published letters in the medical journals, criticising PACE.

"Chalder and colleagues acknowledge that the trial outcomes do not support the hypothetical deconditioning model of GET for chronic fatigue syndrome".[75]

Peter Kemp has written a detailed thirty page critique of the study split into ten sections called the = h.d4e0wlbznjk1 'PACE Trial Analysis'.[76]

Angela Kennedy has made specific critiques of PACE regarding the following areas:[77]

- Serious risks to clinical patient safety caused by unsound claims made about the efficacy of CBT and GET following the PACE trial;

- Gross discrepancies between research and clinical cohorts, and how clinical patients (and the physiological dysfunction associated with them) appear to have been actively excluded from PACE and other research by the research group involved in PACE, which has, ironically, caused serious resulting risks to clinical patient safety in the UK in particular;

- Related to the above, gross discrepancies in how various sets of patient criteria were used (and/or rejected), including but not limited to a changing of the London criteria by PACE authors from its original state, a set of criteria which was already controversial and problematic to start with for a number of reasons;

- Failure of the PACE trial authors to acknowledge the range and depth of scientific literature documenting serious physiological dysfunction in patients given diagnoses of ME or CFS, and how CBT and GET approaches may endanger patients in this context;

- The inclusion of major mental illnesses in the research cohort;

- The distortion by PACE trial researchers of 'pacing' from an autonomous flexible management strategy for patients into a therapist led Graded Activity approach;

- The post hoc dismissal of adverse outcomes as irrelevant to the trial, in direct contradiction to what is scientifically known about the physiological dysfunctions of people given diagnoses of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome;

- The instability of 'specialist medical care' as a treatment category, and the lack of any sound category of 'control' group.

Dutch patient Frank Twisk of the ME-de-patiënten Foundation has also published criticism of the PACE trial.[78]

"The PACE trial investigated the effects of CBT and GET in chronic fatigue, as defined by the Oxford criteria, not in chronic fatigue syndrome, let alone myalgic encephalomyelitis".

"[T]he positive effect of CBT and GET in subjective measures, fatigue and physical functioning, cannot be qualified as sufficient. Mean short form-36 physical functioning scores in the CBT group (62·2) and the GET group (59·8) at follow-up were below the inclusion cutoff score for the PACE trial (≤65)3 and far below the objective for recovery as defined in the PACE protocol (≥85)."

"The vast majority of patients improved subjectively by specialist medical care and APT to the same level as by CBT and GET, without any additional therapies, including CBT and GET, or by other therapies."

"[L]ooking at subjective outcomes at follow-up and objective outcomes in earlier studies, such as physical fitness, return to employment, social welfare benefits, and health-care usage, CBT and GET, like specialist medical care and APT, cannot be qualified as effective".

Tom Kindlon a patient and Vice-Chairman of the Irish ME/CFS Association. He has published extensive criticism of the PACE trial. In 2011 he published a paper on harms associated with Graded exercise therapy.[73]

Mr Kindlon has also written a large number of letters and comments that have been published in medical journals in response to the published papers.

Among many other published letters that have been critical of the trial, many are from people who have identified themselves as patients. For example, most of the letters published by The Lancet criticising the 2011 PACE paper were from patients or representatives of patients' groups.[79][80][81]

ME Analysis: Evaluating the results of the PACE Trial study

Janelle Wiley and Graham McPhee also collaborated with others from Phoenix Rising to create 'ME Analysis: Evaluating the results of the PACE Trial' website summarising their critique of the trial.

It examined the flaws with the PACE trial and came up with 10 conclusions. The 'ME Analysis: Evaluating the results of the PACE Trial' is presented in the form of 10 conclusions. Clicking on each conclusion will lead to a short summary, and clicking on the links underneath each summary will, if you wish, lead you ever deeper into our analysis.

ME Analysis videos by Phoenix Rising

Members of Phoenix Rising including Graham McPhee and Tom Kindlon have collaborated on a set of explanatory videos about flaws in PACE's statistical analyses on YouTube:

- Video 1: The PACE Race

- Video 2: 60 - The new 75

- Video 3: Not so bad

- Video 4: The force of LOGic

- Video 6: ME Recovery Song

- Video 7: How's That Recovery?

ME Charities criticism and complaints

Charities have criticised it including Invest in ME Research.[82] Jane Colby of Tymes Trust wrote a letter to the Guardian.[83] The ME Association have also criticised the PACE trial.

MEAction

MEAction submitted a petition to retract the PACE trial that received over 12,000 signatures.[84] In addition, #MEAction published a 'PACE Trial overview' of the PACE trial and its flaws, produced by patients.[85] MEAction have also produced a factsheet of 'Why ME patients are critical of the PACE trial' which addresses three major myths which have been created by the PACE trial investigators and the harms that these myths have caused. The myths busted included:

MYTH: 1 'The controversy is fueled by a vocal minority of "vociferous" ME militants on the internet,

MYTH 2: M E sufferers oppose GET because they are afraid of exercise.

MYTH 3: ME sufferers oppose CBT because they are afraid of the stigma of mental illness.[86]

Briefing document from a Science for ME working group

Consisting of patients including Tom Kindlon, Sean Kirby and Graham McPhee, this working group has produced a document to concisely explain the flaws in the PACE trial.

ME Analysis videos (2018)

Graham McPhee has created a set of three videos looking again at the PACE trial.

Others including Jessica Kellgren-Fozard, a vlogger and TV producer with a large social media following, created a video in May 2018 called 'Have you been misled...? // What is PACE? // Medical Scandal' which had been viewed over 35,000 times.[87]

Controversy

The PACE Trial has been heavily criticised by patient groups and some researchers and science journalists for a number of methodological problems since its publication. [26][27][28][55][88][89][90][91][92]

Prof Malcolm Hooper's complaints

Prof Malcolm Hooper and Margaret Williams have followed the PACE trial from its inception in 2004 and provided salutary warnings about the possible issues and problems with the conduct of the trial due to their previous knowledge of the principal investigators research.[93][94]

They then published a 400 page critique of the PACE trial in February 2010 'Magical Medicine: How to make a disease disappear'.[95] In February 2011 upon publication of the PACE trial findings, Prof Hooper submitted a comprehensive complaint to the editor of the Lancet[96] and a further detailed response.[97]

Prof Hooper et al in 2011 published further concerns about the PACE trial[98] and have also examined the role of the Science Media Centre and the insurance industry with the PACE trial.[99] The Key Concerns about the PACE trial were also published in 2013 by MEActionUK.[100] Prof Hooper has published a summary of the key dates and chronology of the trial since 2004.[101]

Investigation by public health journalist and academic, Dr. David Tuller

Renewed interest in the trial came in October 2015 with public health expert and investigative journalist Dr. David Tuller's investigative "Trial by Error: The Troubling Case of the PACE Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study" publication on Virology Blog which gave a detailed analysis of PACE's methodological problems. Dr. Tuller continues to publish articles criticizing different aspects of the trial.[102] Some of the main articles for the "Trial by Error" series on the PACE trial are listed below:

- Oct 21, 2015 "Trial by Error: The Troubling Case of the PACE Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study"

- Oct 22, 2015 "Trial by Error: The Troubling Case of the PACE Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study (second instalment)"

- Oct 23, 2015 "Trial by Error: The Troubling Case of the PACE Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study (final installment)"

- Nov 13, 2015 "An open letter to Dr. Richard Horton and The Lancet"

- Jan 7, 2016 Trial By Error, Continued: Did the PACE Trial Really Prove that Graded Exercise Is Safe? (with Julie Rehmeyer)

For a longer list of the main articles on the PACE trial see:

The PACE trial authors, with the exception of their response to Virology on October 30, 2015, have refused to respond to or engage with David Tuller about these concerns; Tuller made requests for comment in 2015 and 2016. Similarly, Richard Horton, editor of the Lancet has refused to respond to Tuller about these concerns or about the retraction of the PACE trial publication. Sir Simon Wessely on behalf of the PACE trial principal investigators did publish an article in November 2015 The PACE trial for chronic fatigue syndrome: choppy seas but a prosperous voyage referring to the growing concerns over the PACE trial. This was published in a blog website called National Elf Service run by the Mental Elf, in which he used an analogy of the clinical trial as an ocean liner crossing the Atlantic.[14]

Further criticism from scientific community

Dr James Coyne, Professor of Health Psychology, at the University Medical Centre Gronigen]] (UMCG), published on PLoS One Blog on 29 October 2015 "Uninterpretable: Fatal flaws in PACE Chronic Fatigue Syndrome follow-up study".[71] He gave a talk at Edinburgh University in November 2015 criticising the PACE trial.[103][104][105][106] He spoke again about the PACE study in Belfast in February 2016 where he described it as "a wasteful trainwreck of a study".[107][108] Professor Coyne has also questioned whether the PACE trial paper could ever have been properly peer-reviewed, given the large number of study authors and the small world of British science.[109] He has continued to critique the PACE trial.[110]

Dr Keith Laws, Professor of Neuropsychology at the University of Hertfordshire has also criticised the PACE trial in a number of blogs on his website in November 2015.[111][112] He also co-authored a letter in the Lancet Psychiatry in 2016 with Dr. Coyne "Results of the PACE follow-up study are uninterpretable".[113]

Science journalist Julie Rehmeyer published an article in Slate magazine in November 2015 called "Hope for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: The debate over this mysterious disease is suddenly shifting" and contrasted the hope that sufferers had with research being conducted in the US and the UK researchers involved with PACE trial.[114] Julie Rehmeyer has continued to criticise the PACE trial with further publications and in conferences.[115][116][115]

Lucy Bailey, a former editor of the Lancet, analysed the PACE trial and provided her comments on the controversy, concluding, "Psychiatrists need to understand that their presence anywhere near this condition is now toxic, and maybe they need to take a step back".[117] Bailey also wrote a letter to the Lancet Infectious Disease called "A case for Retraction?" and has questioned the reasons why actigraphy was dropped late in the trial.[118][119]

Dr Mark Vink, a family physician in the Netherlands, published in the Journal of Neurology and Neurobiology in March 2016 that "[t]he PACE Trial Invalidates the Use of Cognitive Behavioral and Graded Exercise Therapy in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome".[120]

Prof Jonathan Edwards has declared that "PACE is valueless for one reason: the combination of lack of blinding of treatments and choice of subjective primary endpoint. Neither of these alone need be a fatal design flaw but the combination is". He also stated "the authors have not been meticulous in trying to avoid bias that might arise. On the contrary they appear to have acted in ways more or less guaranteed to maximise bias."[66]

In early 2016, Leonid Schneider, a science journalist, criticised the lack of data sharing by the PACE trial authors and the Lancet and its editor Richard Horton's role in the scandal and compared it to other recent Lancet scandals.[121][122][123]

Prof Andrew Gelman, Professor of Statistics and Political Science at Columbia University, NY, examined the Lancet's role in how the PACE trial got taken so seriously and stayed afloat for so long.[124][125][126][127]

Dr Sten Helmfrid published an article in the journal Socialmedicinsk tidskrift in September 2016 called "Studies on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Graded Exercise Therapy for ME/CFS are misleading" that criticized not only the PACE trial, but the entire CBT/GET paradigm for ME/CFS. "The underlying model has no theoretical foundation and is at odds with physiological findings. Surveys suggest that the efficacy of CBT is no better than placebo and that GET is harmful. Therefore, cognitive behavioral therapy and graded exercise therapy for ME/CFS are not evidence based."[128]

Dr Sonia Lee, a clinical epidemiologist, published 30 slides critically appraising the PACE trial in February 2017 and concluding the PACE trial authors should "rectify or retract".[129][130] Dr Lee self-published Research Waste In ME/CFS which compared psychosocial trials using the PACE trial as an example psychosocial trial. Lee found that psychosocial trials were more likely to engage in selective reporting than biomedical trials, that PACE in particular had significant design, evidence and justification weaknesses or omissions, and concluded "it confirms the concerns raised by ME/CFS groups that psychosocial interventions are harmful, and present questionable therapeutic benefits no different to a placebo".[131]

Professor Leonard Jason in the Journal of Health Psychology wrote in February 2017 'The PACE trial missteps on pacing and patient selection' which criticised the issue of patient selection in the trial with the use of the Oxford criteria included those without the disease and the PACE trial investigators did not design and implement a valid pacing intervention in the trial.[132]

Dr Sarah Myhill in her August 2017 video on Medical Abuse in ME Sufferers (MAIMES) called the PACE trial "fraudulent" and "a criminal act" and is an "abuse" of "vulnerable people" and "defrauds them of benefits".[133]

In April 2018, ME/CFS researcher Dr Neil McGregor sent his analysis of the harms in the PACE studies, to Australia's Chief Medical Officer. In it, McGregor stated that "The conclusions within the PACE studies is consistent with a highly biased study which under-estimates, and does not assess, the adverse outcomes in relationship to the disease process. The use of therapies of this type cannot be recommended based upon the data within the PACE study and must exclude the worst affected patients as they were not included in the study assessments."[134][135]

Scientists' open letter to The Lancet and Psychological Medicine

In November 2015, scientists Ronald Davis, David Tuller, Vincent Racaniello, Jonathan Edwards, Leonard Jason, Bruce Levin and Arthur Reingold wrote an open letter to The Lancet citing "major flaws" in the original trial publication and asking for an independent re-analysis of the individual-level trial data.[7] The journal failed to respond.

In February 2016 the open letter was re-published with 36 additional signatures from doctors and researchers including: Dharam Ablashi, Lisa Barcellos, James Baraniuk, Lucinda Bateman, David Bell, Alison Bested, Gordon Broderick, John Chia, Lily Chu, Derek Enlander, Mary Ann Fletcher, Kenneth Friedman, David Kaufman, Nancy Klimas, Charles Lapp, Susan Levine, Alan Light, Sonya Marshall-Gradisnik, Peter Medveczky, Zaher Nahle, James Oleske, Richard Podell, Charles Shepherd, Christopher Snell, Nigel Speight, Donald Staines, Philip Stark, John Swartzberg, Ronald Tompkins, Rosemary Underhill, Rosamund Vallings, Michael VanElzakker, William Weir, Marcie Zinn and Mark Zinn.[56]

Richard Horton, the editor of the Lancet, requested it to be submitted as an official letter but after 6 months of chasing he rejected it and refused to publish the letter.[136][137]

On March 13, 2017 David Tuller and the original signatories to the open letter to the Lancet in 2016 and an additional 37 signatories signed an open letter to the Journal of Psychological Medicine. In total 102 signatories signed this open letter regarding the recovery paper of 2013 to the Journal of Psychological Medicine.

These included scientists and medical professionals including Molly Brown, Todd E. Davenport, Simon Duffy, Meredyth Evans, Robert F. Garry, Keith Geraghty, Ian Gibson, Rebecca Goldin, Ellen Goudsmit, Maureen Hanson, Malcolm Hooper, Betsy Keller, Andreas M. Kogelnik, Eliana M. Lacerda, Vincent C. Lombardi, Alex Lubet, Steven Lubet, Patrick E. McKnight, Jose G. Montoya, Henrik Nielsen, Elisa Oltra, Nicole Porter, Anders Rosén, Peter C. Rowe, William Satariano, Ola Didrik Saugstad, Eleanor Stein, Staci Stevens, Julian Stewart, Leonie Sugarman, Mark VanNess, Mark Vink, Frans Visser, Tony Ward, John Whiting, Carolyn Wilshire and Michael Zeineh.[138][139] Twenty-seven ME charities from seventeen countries also co-signed the open letter including European ME Alliance, 25 Percent ME Group (UK group for severe ME patients), Emerge Australia, Irish ME Trust, ME Association (UK), and International Solve ME/CFS Initiative (US).[140]

On March 23, 2017, David Tuller reported that one of the editors of the Journal of Psychological Medicine, Sir Robin Murray, responded with "an unacceptable response." Tuller restated that "That the editors of Psychological Medicine do not grasp that it is impossible to be “disabled” and “recovered” simultaneously on an outcome measure is astonishing and deeply troubling." The open letter was reposted with signatures from an additional 17 clinicians, scientists or advocates and 23 more charities including Norman E. Booth, Joan Crawford, Valerie Eliot Smith, Susan Levine, and Sarah Myhill.

An additional 25 patient charities to sign included Associated New Zealand ME Society, Deutsche Gesellschaft für ME/CFS and Lost Voices Stiftung (Germany), ME Research UK, ME/CFS (Australia) Ltd, The MEAction Network, Millions Missing Canada, National CFIDS Foundation, Inc. (US), and Open Medicine Foundation (US). No response from the Lancet was received - campaigning in 2018 continued.

Petitions and Protests

On October 28, 2015, The MEAction Network launched a petition addressed to The Lancet, Psychological Medicine and the PACE trial authors, calling for an independent analysis of the data and the retraction of some of the PACE trial's "misleading claims" based on "absurd 'normal ranges' for fatigue and physical function". The petition was closed in February 2016, having gathered 11,897 signatures from people in sixty-four countries.[5][141]

A US petition to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Centers for Disease Control was also launched in late 2015, asking government agencies to remove guidelines and recommendations based on PACE and other studies using the Oxford definition of ME/CFS.[142]

On International ME Awareness Day (May 12th) in 2017 due to the intransigence of the PACE researchers for years, a Millions Missing protest in London resulted in hundreds of patients protesting against the PACE trial.[143]

Breaches of patient's data security by study investigators

In 2006 confidential PACE trial patient data was stolen from an unlocked drawer at King's College London.[144]

Malcolm Hooper documents in Magical Medicine how in 2005 confidential patient data was erroneously released by PACE author Professor Michael Sharpe in relation to another study.[95]

The Centre for Welfare Reform - 'In the Expectation of Recovery'

The Centre for Welfare Reform published a 64 page report in April 2016 examining the PACE trial and relating the study to the biopsychosocial model and its links and influence from the insurance industry and government welfare reforms. The report titled 'In the Expectation of Recovery' by George Faulkner heavily criticised the PACE trial and stated "The way in which the biopsychosocial model has been used and promoted, without good supporting evidence for many of the claims being made, is unethical.” and “Had homeopaths or a pharmaceutical company conducted a trial and presented results in the manner of the PACE trial the British research community would have been unlikely to overlook its problems."[145] Dr Simon Duffy writing in the Huffington Post questioned the motive of the research in 'The Misleading Research at the Heart of Disability Cuts'.[146]

Sense About Science USA

Sense about Science USA (SAS USA) published a major statistical examination of the PACE trial in March 2016. The Executive Director of SAS USA, Trevor Butterworth wrote an accompanying editorial on PACE.[147] Prof Rebecca Goldin of Mathematical Sciences at George Mason University and Director of STATS (a collaboration between SAS USA and the American Statistical Association) wrote the 7000 word statistical critique PACE: The research that sparked a patient rebellion and challenged medicine.[58]

Other major investigations and reports

In August 2016 Julie Rehmeyer presented a critique of the PACE trial at the largest gathering of statisticians in North America, the Joint Statistical Meeting 2016, in Chicago titled Bad Statistics, Bad Reporting, Bad Impact on Patients: The Story of the PACE Trial. Rehmeyer said "When I went through the slides showing the changes to the physical function criterion for recovery, I saw jaws drop."[148]

PACE Trial in UK Parliament

The PACE Trial has been the subject of a number of parliamentary enquiries by parliamentarians mainly the Countess of Mar. The Countess of Mar asked questions of the government via a short debate in the House of Lords on the assessment of the PACE trial on 6 February 2013. A video and transcript is available on YouTube and Hansard.[149][150] Comments and analysis on the PACE trial and its establishment defenders has also been made by advocates.[151]

During the court case in 2015 by Matthees and the Information Commissioners Office v QMUL it was stated by Peter White that he regarded parliamentary debates as "harassment" and had to brief those taking part in the debate.

In November 2016, Kelvin Hopkins MP asked seven written questions relating to the PACE Trial including "request that the Medical Research Council conducts an inquiry into the management of the PACE trial to ascertain whether any fraudulent activity has occurred." and "prevent the PACE trial researchers from being given further public research funding until an inquiry into possible fraudulent activity into the PACE trial has been conducted."[152]

The Countess of Mar has also asked in February 2017 the UK parliament's Committee of Public Accounts to investigate the use of public funds on the PACE Trial and the PACE authors use of public funds to resist requests to release anonymised clinical trial data. Her letter included a report which stated the trial was "professional misconduct and/or fraud" and "Professor White obtained ethical approval for the study under false pretences".[153]

Response to criticism

Response

The trial investigators have replied to some criticism of the trial but have been much criticised as being evasive and not responding to the issues raised.

Some of their response to letters to The Lancet concerning their main analyses,[154] Psychological Medicine concerning their recovery analyses,[138] and Lancet Psychiatry concerning their secondary mediation analyses [155] and long-term follow-up paper.[156] A letter to the BMJ by Tom Kindlon[157] drew a reply from the authors[158] that in turn received 31 responses of its own.[159]

Since the controversy with criticism from the scientific community they have largely not responded to the key concerns and have repeated their earlier arguments.

The investigators have also responded to a 14,000-word critique by public health expert and journalist Dr David Tuller.[55] Dr Tuller wrote a rebuttal to their response.[88] He has said, “The PACE authors have long demonstrated great facility in evading questions they don’t want to answer”.

Professor James Coyne reported that he agreed to debate the authors on health website National Elf about the trial but that they declined.[160] Professor Simon Wessely was given the vacated National Elf spot and wrote a lengthy article praising the trial, noting that he once described it as "a thing of beauty" and saying, "We can accept that PACE was a good trial and we can have some confidence in its findings".[14]

Allegations of harassment, death threats and smear campaign

During the criticism of the PACE trial by patient groups the PACE trial psychiatrists publicised that they were receiving death threats and harassment.

The PACE trial investigators and Professor Simon Wessely have publicly claimed they have been harassed and subjected to death threats.[161][162][163][164][165][166][167][168] A feature article in the BMJ (read by most UK doctors) was published in June 2011 called 'Dangers of research into chronic fatigue syndrome'.[169] The Times article was titled 'Doctor’s hate mail is sent by the people he tried to cure'.[170] An article was also published in the Sunday Times magazine with Simon Wessely repeating the death threats narrative.[171] One article was even called ‘It’s safer to insult the Prophet Mohammed than to contradict the armed wing of the ME brigade’.[172]

However, the PACE authors and their supporters have been accused of blurring the line between harassment and legitimate criticism of the study. Documentation obtained under the Freedom of Information Act from meetings in 2013 that were attended by some of PACE’s principal investigators include a statement that “harassment is most damaging in the form of vexatious FOIs [Freedom of Information requests].”[173] This framing of FOIA requests as harassment is widely taken to be a reference to the PACE authors, who have complained about the number of FOI requests that they have received for data[174] and who have dismissed several as "vexatious":[175][176][177] the Information Commissioner's Office was told that Professor Peter White "believes that the requests are clearly part of a campaign to discredit the trial” and that “the effect of these requests has been that the team involved in the PACE trial, and in particular the professor involved, now feel harassed and believe that the requests are vexatious in nature."[174]

The criticisms of the trial's methodology and analyses by patients and others has been referred to by the investigators - and The Lancet - as part of a campaign to undermine the the study. In an editorial comment that accompanied letters criticising the trial, The Lancet described the trial as “rigorously conducted” and questioned whether the “coordination of the response... has been born... from an active campaign to discredit the research”.[178] In an interview on Australian national radio shortly after publication, Dr Richard Horton, The Lancet’s editor, described patients who criticised the trial as “a fairly small, but highly organised, very vocal and very damaging group of individuals”.[179]

But some accuse the investigators of a campaign against patients, labelling them as harassers to undermine their criticisms of the trial, including Angela Kennedy.[180]

The PACE trial authors refused to provide anonymised data to many individuals and also refused to accept the Information Commissioners Office decision for QMUL to release the data in 2015 (see Release of Data/Information Tribunal below). During the PACE trial authors appeal to the Tribunal an article was published during this period by their associates in Nature in which they bizarrely appeared to use projection in describing disabled ME sufferers as “hard-line opponents” of research into chronic fatigue syndrome and compared them with industry lobbyists such as tobacco and climate change denialists.[181][182] Public health expert and journalist David Tuller, who has said, "Wrapping themselves in victimhood, the [PACE authors] have even managed to extend their definition of harassment to include any questioning of their science and the filing of requests for data — a tactic that has shielded their work from legitimate and much-needed scrutiny."[183][184]

The Science Media Centre (SMC) was found to have orchestrated and publicised the false narrative in 2011 in the UK media about extremists harassing researchers.[185][186] An article in the Establishment in May 2016, The Hidden Battle For The Rights Of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Sufferers summarised the campaign to smear ME sufferers and how these psychiatrists after categorising ME as a psychological over two decades then were able to use institutional gaslighting when patients were question the scientific validity of the trial and to stop access to data requests from the PACE trial by framing them as harassment and abuse. Catherine Hale has written about the 'Politics of Stigma' created for ME sufferers by the PACE trial authors.[187] Peter Tatchell, a human rights advocate has supported ME sufferers for their human rights against the psychotherapies and the PACE trial and defended them from the smear campaigns by the psychiatrists similar to what he faced in his advocacy in the 1970s.[188][189][190] Ethics experts Charlotte Blease and Diane O'Leary have investigated ethics and injustice in the behavior of some researchers in the ME/CFS field and the effects of government and institutional actions on patients.

No evidence of anyone with ME/CFS in relation to these matters being charged by the police/law enforcement or convicted in the Courts with harassment and death threats has come to light, despite a number of ME advocates attempting to find evidence, including filing Freedom of Information Act requests to public bodies.[191][191][192][192][193]

Calls to release data

Open data commitments

The study authors have been criticised for failing to follow the requirements of the Medical Research Council (who provided significant funding for the trial) to release anonymised trial data.[194]

The 2012 PACE cost-effectiveness paper[20] was published in the journal PLoS One. That journal requires authors, as a condition of submitting their papers, to agree to release the anonymized trial data underlying the paper's analyses upon request. In November 2015 Professor James Coyne made a request to the PACE authors on that basis, but the authors treated his request as a Freedom of Information request and refused it.[195][196] However in March 2016 the PLoS One journal confirmed they had requested the investigators to release the trial data, as they committed to do prior to publication.[197][198]

In 2015 Peter White lobbied the UK government through his university QMUL and the Science Media Centre to restrict the Freedom of Information Act 2000 for universities especially for controversial research and cited the PACE trial and compared ME patients requesting data with "climate change science, and research into the health effects of tobacco".[199][200]

Freedom of Information requests

The PACE trial investigators have been asked for 160 pieces of separate information in 35 Freedom of Information requests since 2011.[174] They have dismissed at least three of these claims as "vexatious".[175][176][177][64][201]

A ruling by a UK government body, the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO), on October 27, 2015 ordered Queen Mary University of London (QMUL, the institutional base of the PACE trial's lead investigator Peter White) to release the trial data to a patient who had requested it, subject to appeal within 28 days.[202] Three Freedom of Information requests from 2012 and 2013 were included in the ICO's decision.[203][204][61] An appeal by QMUL was heard by the First-Tier Tribunal on 20-22 April 2016. QMUL responded to a freedom of information request confirming the cost of its legal fees for the tribunal totalled £245,745.27 (around USD 350,000).[205][206][207] The First-Tier Tribunal judgement was published on August 16, 2016, roundly dismissing the appeal by QMUL, and deciding that the PACE trial data should be released.[208][209] The university has not yet stated whether it will appeal the judgement.[210] The PACE patient consent form was also the released through a Freedom of Information request.[211]

Dr Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet, stated on April 18, 2011 in a national Australian radio interview: "The Freedom of Information requests and the legal fees that have been racked up over the years because of these vexatious claims has added another £750,000 of taxpayers’ money to the conduct of this study".[97]

Data requests from scientists

Professor James Coyne has publicly called for the trial data to be released. He has repeatedly criticized the PACE investigators for failing to abide by modern expectations concerning "open data".[212][213][214][215][216][217][218][219][220]

Professor Coyne's own request for the data was dismissed under the Freedom of Information Act by the study authors as "vexatious" and as having an "improper motive".[175]

Scientists Ronald Davis, David Tuller, Bruce Levin, and Vincent Racaniello requested the PACE trial data in December 2015.[221] Their request was rejected by the trial investigators.[222] On International ME Awareness day in May 2016 in an interview with an advocate's article called PACE-Gate, Dr Racaniello stated "I think they are going to ignore, obfuscate, and give their usual responses until we are all dead. I don’t have hope that the PACE authors, or Lancet, will respond in any meaningful way until there is more of an outcry."[223]

ME Charities and others calls for data release

A number of patient charity groups and individuals have called for the release of the PACE data, including some outside the ME/CFS community who advocate "open data" in science. These calls include:

- 2016: open letters from two patient charities, in Australia, ME/CFS Australia (SA) Inc and Emerge Australia, calling for the data to be released.[224][225]

- 2016: an open letter the European ME Alliance (EMEA) representing patient group charities from 12 European countries (Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Holland, Iceland, Ireland, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and UK), calling for the data to be released.[140]

- 2016: an open letter by Mark Berry of Phoenix Rising, a US based non profit with the largest ME patient forum membership in the world, calling for the data to be released.[226]

- 2016: open letters from British patient charities Action for ME, Invest in ME, ME Association, Tymes Trust, ME Research UK, Hope 4 ME & Fibro NI, the Welsh Association of ME & CFS Support and the 25 Percent ME Group.[227][228][229][230][231][232][233][234][235]

- 2016: an open letter from the Irish ME Trust charity.[236]

- 2016: an open letter from a Canadian patient group, the National ME/FM Action Network.[237]

- 2016: an open letter from two Belgian patient organisations, ME-Gids and WUCB.[238]

- 2016: an open letter from a Dutch patient group, Groep ME-DenHaag / The Dutch Citizen’s Initiative for ME patients[239] and a joint letter from three further dutch patient group charities, ME/CVS Vereniging, ME/CVS Stichting Nederland, Steungroep ME en Arbeidsongeschiktheid[240]

- 2016: an article, "PACE trial and other clinical data sharing: patient privacy concerns and parasite paranoia", by Leonid Schneider, an independent science journalist.[122]

- 2015: a blog post by Dr Richard Smith, former editor of The BMJ, who said that the PACE authors' institutions were "making a mistake .. the inevitable conclusion is that they have something to hide."[241] and in article for F1000 Research.[242]

- 2016, Release the PACE trial data: My submission to the UK Tribunal, James Coyne, Aug 18, 2016.[243]

A total of 29 patient charity groups from 15 countries wrote in support of releasing the anonymized PACE trial data.[244][245]

A ME charity polled on the question "Should or should not the anonymised data from the PACE trial be released for independent analysis?" By March 17, 2016, 1391 voters took part and 99% (1378 voters) voted for 'Should be released'. 0% (5 voters) voted for 'Should not be released'.[246]

Both cofounders of Retraction Watch, Ivan Oransky and Adam Marcus, added their weight behind patients in the refusal of the PACE trial investigators to release the anonymised data in article in STAT News feature 'The Watchdogs Keeping an eye on misconduct, fraud, and scientific integrity' To keep science honest, study data must be shared and concluded "when researchers refuse to share data, and how they came up with it, they lose the right to call what they do science".[124]

This battle was reported in the Wall Street Journal by Amy Dockser Marcus on 7 March 2016 as Patients, Scientists Fight Over Research-Data Access, which featured quotes from David Tuller, Tom Kindlon, Anna Sheridan Wood, James Coyne.[247] Professor Peter White responded to the article with a letter to the WSJ published 24th of March, 2016, claiming that "The main reason that my colleagues and I have been unable to release data to members of the public who ask for it is that we don’t have the consent of the trial participants to release their data in this way, and we are ethically bound to act in the best interest of our patients."[248]

Release of Data

Alem Matthees, an Australian ME sufferer, submitted a FOIA request to the PACE trial authors who were ordered to provide the requested data by the Information Commissioners Office. This decision was appealed by them to the Information Tribunal and was heard on April 20th 2016 at a three day hearing.

Information Tribunal

Mr Alem Matthees' original PACE trial data Freedom of Information Act request for the release of PACE trial data to Queen Mary University of London (QMUL) was submitted on March 24, 2014. QMUL refused to release the requested data and Mathees complained to the Information Commissioners Office. The Information Commissioners decision was made on October 27, 2015 and concluded that QMUL should release the data.[249][202] The PACE investigators appealed on November 23, 2015.

QMUL appealed the decision, wishing to continue to withhold the PACE trial data, which led to a tribunal in 2016.[250][251] The Information Commissioner's response to the Tribunal as First Respondent of January 12, 2016 and Mr Alem Mathees Main response to Tribunal as Second Respondent was also submitted to the Tribunal for the three day hearing from April 20th-22nd, 2016.[252] The Information Rights Tribunal Judgement was finally published on August 16, 2016.[209][253] The Tribunal upheld the original ICO decision and rejected the appeal by the PACE investigators and ordered QMUL to release the anonymised data to Mr Matthees.

The tribunal took evidence under the normal rules of court. The tribunal also concluded of the expert witness for the PACE authors that "It was clear that his assessment of activist behaviour was, in our view, grossly exaggerated and the only actual evidence was that an individual at a seminar had heckled Professor Chalder" and "clearly in our view had some self-interest, exaggerated his evidence and did not seem to us to be entirely impartial. What we got from him was a considerable amount of supposition and speculation, with no actual evidence to support his assertions or counter the respondents arguments." The tribunal panel noted that the Commissioner had referred to Professor Anderson's "wild speculations" that "young men, borderline sociopathic or psychopathic" would attempt to identify trial participants from the anonymised data, and said that his views "do him no credit".[254]

The decision noted in the evidence that "Contrast instead Professor Chalder when she accepts that unpleasant things have been said to and about PACE researchers only, but that no threats have been made either to researchers or participants. The highest she could put it was some participants stated that they had been made to feel "uncomfortable" as a result of their contact with and treatment from her, not because of their participation in the trial per se. There is no evidence either of a campaign to identify participants nor even of a risk of an 'insider threat'."

Moreover, regarding the independent Cochrane review it was admitted in the tribunal that "Professor Chalder states that disclosure to the Cochrane review does not count as disclosure to independent scientists as all three of the PACE principal investigators sat on the review panel."

Additionally, a UK ME sufferer submitted a FOI request in June 2016 and established that the PACE trial investigator's university paid £245,745.27 for legal fees to defend their case in the tribunal against the original ICO decision.[255][256]

The lead PACE investigator's university issued a statement the same day stating "We are studying the decision carefully and considering our response".[210] An open letter in support of Alem Matthees was sent to the university and signed by Dr Ronald Davis, Dr Jonathan Edwards, Dr Rebecca Goldin, Dr Bruce Levin, Dr Zaher Nahle, Dr Vincent Racaniello, Dr Charles Shepherd and Dr John Swartzberg strongly urging them to not appeal further.

The ME community through #MEAction posted a plea to the PACE trial lead authors to "pursue a complete retraction of their PACE trial paper from the Lancet and all associated subsequent papers from their relevant journals." and to "[e]nd this tragedy now."[257] QMUL did not appeal and released the data to Matthees.[258] QMUL finally decided not to appeal a second time, and released the PACE trial data.[259]

Results of Reanalysis of the PACE trial data

Virology blog published the re-analysis on September 21, No 'Recovery' in PACE Trial, New Analysis Finds and concluded "The results should put to rest once and for all any question about whether the PACE trial's enormous mid-trial changes in assessment methods allowed the investigators to report better results than they otherwise would have had. While the answer was obvious from Dr. Tuller's reporting, the new analysis makes the argument incontrovertible."

The full re-analysis was published as A preliminary analysis of 'recovery' from chronic fatigue syndrome in the PACE trial using individual participant data and was conducted by Alem Matthees, Tom Kindlon, Carly Maryhew, Philip Stark and Bruce Levin and stated "This re-analysis demonstrates that the previously reported recovery rates were inflated by an average of four-fold.".[260]

On August 19, 2016 The Centre for Welfare Reform also published an update to its earlier 64 page report from April 2016.[261]

A critical commentary and preliminary re-analysis of the PACE trial was published in December 2016 in the Journal of 'Fatigue: Biomedicine, Health & Behavior' by Dr Carolyn Wilshire, Tom Kindlon, Alem Matthees and Simon McGrath which found that "The claim that patients can recover as a result of CBT and GET is not justified by the data, and is highly misleading to clinicians and patients considering these treatments.[260][262]

'A Rejoinder to Sharpe, Chalder, Johnson, Goldsmith and White' was published by Dr Carolyn Wilshire, Tom Kindlon and Simon McGrath in response to the PACE authors reply to their original publication .[263] Wilshire et al disproved again the PACE trials misleading claims as recovery was a strong claim and did not adhere to the core meaning of the word, no evidence that the original protocol specified definition was too stringent and absolute recovery rates from other studies were not legitimate source of support for the recovery definition used. It reinforced the original conclusion that "The PACE trial provides no evidence that CBT and GET can lead to recovery from CFS. The recovery claims made in the PACE trial are therefore misleading for patients and clinicians".

Instead of engaging with critics by releasing other additional requests for data, the PACE trial authors updated their guidelines in January 2017 for those requesting access to the PACE trial data which further restricted access by requiring "formal agreement" with "precise analytic plans, and plans for outputs".[264] Prof James Coyne commented that it is "a ruse to trap the unwary in endless haggling and appeal, while protecting the PACE investigators from the independent reanalysis of the claims, which they have already declared poses a reputational risk to them".[265]

Scientific and Media response

Despite patients and critics not having access to the Science Media Centre the media coverage especially outside the UK was extensive. For a full list of the scientific and media response to the PACE trial data release and reanalysis, see the article:

Journal of Health Psychology 'Special Issue on the PACE Trial'

A special edition of the Journal of Health Psychology was published on July 31, 2017, by the editor, Dr David Marks with an editorial - Special Issue on the PACE Trial and accompanying all 20 Editorials & Commentaries.[266]

A press release was put out on July 31, 2017, called The PACE Trial: The Making of a Medical Scandal.[267][268]

Prof Coyne explained in his blog of the "[l]ast ditch attempt to block publication of special issue of Journal of Health Psychology foiled" and that anonymous and powerful PACE proponents made threats to the publisher of JHP, SAGE Publications, that made them reluctant to publish the special edition. explained in his blog "Some threats were made to Sage Publications, the publisher of Journal of Health Psychology, which expressed a reluctance to go forward as planned. As often happens with these kind of pressures, we weren’t told the identity of the complainant. It was clear that whoever s/he was, this person was powerful in being able to grind to a halt of making the special issue available, complete with the introductory editorial that was not previously available.'"[269]

It transpired that "When the effort to block publication of the special issue failed, the PACE investigators got criticism posted at Science Media Centre." [270]

The Science Media Centre put out its own "expert reaction" press release to UK journalists minutes before the special edition was available to spin the story about the PACE scandal and distract and refocus away from the central problems with the scandal.[271] The Science Media Centre ignored the glaring problems and instead made personal attacks agains the authors.

Dr David Tuller deconstructed "these rather pathetic efforts at defending the indefensible" from the Medical Research Council (MRC), an unnamed University of Oxford spokesperson, and Malcolm Macleod in The Science Media Centre's Desperate Efforts to Defend PACE.[272] It was stated by a whistleblower that Michael Sharpe was the person who complained to the Journal to block publication.[273] This was published on social media by a ME advocate and although unverified, due to its importance as it was the principal author of PACE trial, it is being documented and referenced here.

The Times (UK) published two articles that covered the issue but with a spin and focus on disagreements between scientists and resignations rather than the central issues in the Special Issue on the PACE trial scandal.[274][275][276][277] The impact of the decades long denial by the PACE authors of the disability could be seen in the Express article Is chronic fatigue syndrome real? Life-threatening condition can leave sufferers bed bound.[278] The Daily Mail reported on it with Angry scientists throw insults at each other over the results of a £5 million taxpayer-funded study into chronic fatigue syndrome.[279]

US local media reported on it as 'Chronic fatigue syndrome reality conflicts with medical study'. Other international media reporting it including the Metro Netherlands 'Wetenschappers vallen door de mand'. Forskning (Research) of Norway reported it as 'Hard kritikk av stor ME-studie'/'Hard criticism of major ME study' . Seeker published on both the PACE trial scandal and the 2017 Stanford Cytokine study and concluded "The fact that this new study and the journal issue came out at virtually the same time is significant. The study and the journal "reinforce each other," Tuller said".[280]

Journalist Jerome Burns in the Daily Mail wrote the article Why are doctors and patients still at war over M.E.? How the best treatment for the debilitating condition is one of the most bitterly contested areas in medicine.[279] David Tuller commented on social media "Amazing to see a fair story on ME like this in the UK press. Seems like the PACE story has broken through" as it was a breakthrough in the UK media because of the influence of the PACE authors and the Science Media Centre.[281]

The iNews reported it as "You're a disgusting old fart neoliberal hypocrite" – scientists in furious row over ME study with a prominent and groundbreaking comment from Dr David Marks in the national UK media "The many wrongs committed by psychiatry and medicine to the ME/CFS community can only be righted when the Pace trial is ultimately seen for what it is: a disgraceful confidence trick to reduce patient compensation payments and benefits."[282]

The Medical Independent in Ireland published an article referencing Dr Keith Geraghty and Nasim Marie Jafry's work with a literary take on the changing narrative of ME from neurological to biopsychosocial and culminating in the PACE trial and a whole special issue dedicated to the scandal.[283]

The President of the IACFS/ME Prof Fred Friedberg stated of the Special Edition "the most misleading and damaging aspect of the PACE trial was contained in the subsequent reporting of "recovery"" and "This can have the effect of delegitimizing the illness even more and may discourage biomedical research on ME/CFS". He continued "misleading reports that inflated the benefits of the PACE trial, which were widely cited in the mass media at the time, may have further undermined illness credibility with the research community" as far as the United States.[284] In contrast a separate investigation into research funding it was established Peter White as receiving the most research funding and a near monopoly from the UK government and taxpayers out of all researchers despite protests from patients.[285]

Learn more

- 2018, = 11:01:20&out = 11:31:59 UK Parliament debate on ME Treatment - UK Parliament (video), Hansard transcript

- 2018, PACE trial and its effect on people with ME (alternate video #2 - UK Parliament via YouTube

- 2018, PACE trial and its effect on people with ME (alternate video #3 - UK Parliament via YouTube

- 2018, PACE trial and its effect on people with ME (alternate video #4 - UK Parliament via YouTube

- 2017, 'Special Issue on the PACE Trial' - The Journal of Health Psychology

- 2016, Bad science misled millions with chronic fatigue syndrome. Here’s how we fought back, Julie Rehmeyer, Stat News, Sep 21, 2016.[286]

Reaction by Scientific, Medical and ME Communities

The PACE trial was scientifically discredited but the impact of it on the medical community has continued especially in the UK.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) amendment, US The US government agency called the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) revised its earlier recommendations about found that when studies of CBT and GET, including PACE, that used the Oxford criteria for CFS were excluded, there was no evidence for graded exercise and only weak evidence for CBT.[287] Mary Dimmock led the way on this issue.[287]

PLOS Expression of Concern

Prof James Coyne had requested anonymised data in 2015 from the PACE trial authors from the Cost Effectiveness paper. He pursued this request throughout 2015 and 2016 but was also refused as "vexatious". After 18 months, PLOS issued an Expression of Concern on May 2nd 2017. It stated "We conclude that the lack of resolution towards release of the dataset is not in line with the journal's editorial policy and we are thus issuing this Expression of Concern to alert readers about the concerns raised about this article.[288] The editors of PLOS One, Iratxe Puebla and Joerg Heber, wrote in PLOS One Blog "Since we feel we have exhausted the options to make the data available responsibly, and considering the questions that were raised about the validity of the article's conclusions, we have decided to post an Expression of Concern to alert readers that the data are not available in line with the journal's editorial policy".[289] Retraction Watch reported on the development.[290]

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), US

David Tuller reported in July 2017 that the CDC had updated their treatment recommendations and that all mention of CBT and GET as treatment or management strategies had "disappeared". Tuller reported that the key members of the PACE trial had a long history with the CDC and "For advocates, the CDC's removal of the CBT/GET recommendations represents a major victory. The removal of CBT and GET has been "heralded as an important" by patient charities.[291][292]

In September, David Tuller and Julie Rehmeyer wrote an article in STAT exploring Why did it take the] CDC so long to reverse course on debunked treatments for chronic fatigue syndrome?.[293] NPR reported on the change in the CDC recommendations and that exercise can make the disease worse and criticised the seminal paper Sir Simon Wessely from 1989 that led to exercise as a treatment and the PACE trial.[294] In November 2017, the New York Times published an article stating that longstanding advice to exercise was now recognised as not only ineffective but counterproductive, and referred to the CDC and NICE decision to review the recommendations.[295]

UK reaction from the Journals - Lancet, Psychological Medicine and Guideline Provider - NICE

The UK medical and scientific establishment have been obstinate in changing their position to reflect the flaws of the PACE trial as the PACE trial investigators are highly influential and senior members of the UK establishment. The Lancet have refused to retract the study as yet. Psychological Medicine have also refused to retract the study as well.

The controversial NICE guidelines were challenged by patient groups after the PACE trial was discredited by way of petitions and challenges by ME patient groups in 2017. ME sufferers have taken other actions due to the UK medical establishment intransigence of acknowledging the issues. The Medical Research Council (MRC) and its Chief Executive continued to defend the trial and in a statement dated August 28, 2018 said that as funders of the PACE trial we reject the view that the scientific evidence provided by the trial was unsound.[296]

Jerome Burns in Health Insights UK published a follow up article to his 2016 articles on the PACE trial in the article headlined 'The claim that the cure for the crippling fatigue of ME/CFS was to change your mind always seemed bizarre. Now it really is on the way out…' The journalist stated he thought it would be big story in 2016 with lots of repercussions but the UK press largely ignored it and he revisited the story in 2019 due to professional opinions changing against CBT/GET, with the recent House of Commons debates and the impending revision of the NICE guidelines.[297]

Continued campaigning

Mary Dimmock wrote a comprehensive report Clinical Guidance for ME: “Evidence-Based” Guidance Gone Awry in January 2018 that details how the PACE trial and similar studies based on flawed science led to evidence-based reviews and clinical guidance recommending harmful treatments for ME patients.[298][299]

ME sufferers campaigned against the PACE trial in the Millions Missing protests around the world in 2018, and about the adverse effects of the trial on on biomedical research. As part of this a 'Song for ME: Blowin in the Wind' (available on YouTube) was recorded by ME patients from 7 countries around the world which included the lyrics "How many times must an idea fail...Before it is seen to be flawed?...And how many flaws can a trial embrace...Before it is seen as a fraud?...Yes and how many wounds must its victims expose... Before they’re no longer ignored?".[300]

Dr Racaniello sent another open letter with nearly 100 signatories including scientists, clinicians, academics, lawyers and other experts to the editor Richard Horton at the Lancet due to receiving no response two years later to the original letter from February 2016. The letter again asked for an independent re-analysis from independent reviewers outside UK psychiatry who have no conflicts of interests involving the PACE investigators and the funders of the trial.[301] Another letter of appeal was sent with signatories including 65 ME patient organisation / charities and also this time with 10 Members of Parliament signing the open letter to Richard Horton and the Lancet.[302] The Times (UK) reported on the third letter in its article Call for review of 'flawed' ME research in Lancet letter and stated at the end, "The Lancet declined to comment".[303] The BMJ who were supportive of the PACE trial previously reported it as 'Pressure grows on Lancet to review “flawed” PACE trial' and also approached the Lancet for comment.[304] In a letter to the editor of The Times, the Chief Executive of the MRC, Fiona Watt continued to defend the PACE trial.[303][305]

Additional Scientific Publications

BMC Psychology - Re-analysis by Wilshire et al

BMC Psychology published on March 22nd, 2018 Rethinking the treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome—A reanalysis and evaluation of findings from a recent major trial of graded exercise and CBT by Carolyn Wilshire, David Tuller, Tom Kindlon, Alem Matthees, Keith Geraghty, Robert Courtney and Bruce Levin.[306] It concluded these findings raise serious concerns about not only the PACE trial but the robustness of the claims made about the efficacy of CBT and GET as a whole. One of the early critics and author, Robert Courtney, died shortly before the paper was published.[306]

Once again, the Science Media Centre on the eve of the publication organised three media briefings for journalists and news organisations, and published a CFS/ME factsheet plus two briefings in what was seen as an attempt to reduce the impact of the publication and spin the story.[307][308] One of the patient authors of the PACE reanalysis asked other patients to contact journalists to ensure they cover the publication and to ensure they have the full facts.[309] Despite the pressure and Science Media Centre briefings, the media did report on PACE trial reanalysis. The Times reported it as Findings of £5m ME chronic fatigue study 'worthless'. Even the publicy-funded news organisation, the BBC, reported on it with Chronic fatigue trial results 'not robust', new study says. The Daily Mail, Huffington Post and other UK national and local media reported on the story.[310][311][312] The news was reported in Europe by Health Europa.[313] The Canary's Steve Topple published in-depth coverage of the reanalysis paper.[314] The NEJM JWatch publicised this to physicians.[315] The European Health Journal also republished the paper.[316]

In their correspondence to BMC Psychology published on March 12, 2019 PACE trial authors Michael Sharpe, Kimberley Goldsmith and Trudie Chalder responded to the re-analysis by Wilshire et al, with The PACE trial of treatments for chronic fatigue syndrome: a response to Wilshire et al. They restated that "both CBT and GET, when given appropriately as supplements to specialist medical care, are more effective at improving both fatigue and physical functioning in people with CFS, than are APT or SMC alone." and that they found "no good reason" to change the conclusions of the PACE trial.[317] Wilshire and Kindlon also responded in BMC Psychology with 'Response: Sharpe, Goldsmith and Chalder fail to restore confidence in the PACE trial findings.[318] In the rejoinder Wilshire and Kindlon clarify the misconception in the PACE trial author’s commentary, and address the seven additional arguments they raise in defence of their conclusion. They concluded "New arguments presented by Sharpe et al. inspire some interesting reflections on the scientific process, but they fail to restore confidence in the PACE trial’s original conclusions." It was also stated that unjustified optimism of CBT/GET fuelled by the PACE trial has caused many consequences including hindering the search for effective treatments and that the debate around the PACE trial will have implications reaching far and beyond.

Other journals

Also in March 2018, the British Journal of Healthcare Management published a summary of the controversy over the decades and the scandal over the last two years.[319]