Biopsychosocial model

The biopsychosocial model (BPS model) or cognitive behavioral model (CBM) looks at biological, psychological and social factors to explain why disorders occur and is a tool used by psychologists to examine how psychological disorders develop.[1][2]

| “ | Exercise or activity programmes are the archetypal BPS intervention. This was shown to us in our trial when we used graded exercise therapy in chronic fatigue syndrome.[3] | ” |

—Peter White, Biopsychosocial Medicine | ||

BPS model in chronic fatigue syndrome[edit | edit source]

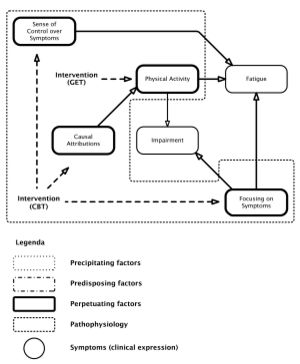

Fatigue: the subjective feeling of fatigue; fatigue subscale of the Checklist Individual Strength. Focusing on (Bodily) Symptoms: somatisation subscale of the Symptom Checklist. (Level of) Physical Activity: Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) subscale mobility (SIP-MOB) and the Physical Activities Rating Scale. (Functional) Impairment: impairment in daily life; subscale of activities at home of the SIP. Sense of Control (over Symptoms): selected items of the modified Pain Cognition List on a specific five-point scale. Causal Attributions: Causal Attributions List (high scores: physical attributions, low scores: psychosocial attributions).

Source: Maes, M., & Twisk, F. N. (2010). Chronic fatigue syndrome: Harvey and Wessely's (bio) psychosocial model versus a bio (psychosocial) model based on inflammatory and oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways. BMC medicine, 8(1), 35. License: CC-BY-2.0

Vercoulen et al (1998) created a highly influential biopsychosocial (BPS)model for "chronic (subjective) fatigue" which was used for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, and justified the use of both cognitive behavioral therapy and graded exercise therapy as treatments.[4][5] However, Vercoulen et al's BPS was developed using patients that did not meet any recognized diagnostic criteria for CFS, instead they selected a mix of patients with idiopathic chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome;[4] only 68% of these patients experienced post-exertional malaise, which later became regarded as the hallmark symptom of ME/CFS.[4]

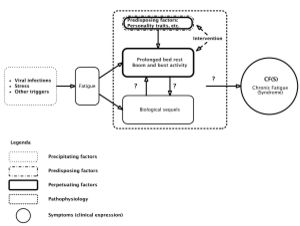

Wessely and Harvey (2009) proposed a development of Vercoulen's biopsychosocial model for not only chronic fatigue syndrome, but for all causes of fatigue, including psychiatric disorders, biological illnesses including AIDS, and fatigue without a known cause.[6] Wessely and Harvey's model has been referred to as a psychosocial model.[6][5] This theoretical model proposed that the all chronic fatigue syndrome and all fatigue was caused by the 3Ps: predisposing factors (e.g. personality traits or other pre-existing risk factors), precipitating factors (e.g. a virus, stress or other trigger) and perpetuating factors (psychological or behavorial factors, e.g., too much rest, being excessively focused on symptoms, beliefs about the illness being caused by a virus, or the patients' other thoughts and behaviors). It did not recognize a genetic predisposition for CFS. [5]

History[edit | edit source]

In a 1977 article in Science,[7] psychiatrist George L. Engel called for "the need for a new medical model." The BPS model is the dominant model used to understand mental illness and combines biological, psychological and social factors.

Evidence[edit | edit source]

Song and Jason (2005) concluded that their "current investigation found that the Vercoulen et al. model adequately represented chronic fatigue secondary to psychiatric conditions but not CFS."

Criticism[edit | edit source]

Song and Jason (2005) attempted to replicate Vercoulen's model, but found it did not fit patient data.[8]

Vercoulen et al. (1998) suggested their findings indicated that individuals with CFS attribute their symptoms to physical causes, are overly preoccupied by physical limitations, and do not maintain regular activity. According to this model, these factors cause individuals with CFS to be functionally impaired and to experience severe fatigue. The fact that this model could not be replicated with either the CFS or those with medical reasons for their chronic fatigue... suggests an important distinction between individuals with chronic fatigue due to a psychiatric condition versus CFS. In other words, the present study does not support a purely psychogenic explanation for CFS.

The BPS model has been criticized for being inappropriately applied to organic biological diseases, and medically unexplained physical symptoms (diseases that cannot yet be fully explained by medical science). Psychologization is the assumption that a disease or illness that cannot yet be explained by medical science must be wholly or partlypsychological in nature, and is used to justify psychological treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy.

BPS models have frequently been applied to ME/CFS, fibromyalgia (FM/FMS), peptic ulcers and other illnesses that are now understood to be physiological diseases.[3] Davey Smith states that peptic ulcer was "the classic BPS disease" but that "cognitive behavioral therapy rather disturbingly had no effect"; only the discovery of helicobacter pylori in 1983 allowed the patients to be cured.[3]

The application of the BPS model for ME/CFS has led to graded exercise therapy (GET or GES) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) as treatment for ME/CFS in a number of countries including the UK.

Controversy[edit | edit source]

The use of the BPS model, and its CBT and GET treatments, in ME/CFS has been heavily criticized by many researchers, charities and patient groups.[9][10] The BPS model provides the justification for the use of exercise therapy in ME/CFS.[3]

These controversial treatments were used in the PACE trial, which David Tuller, Keith Geraghty, Robert Courtney, Angela Kennedy, Tom Kindlon, Alem Matthees, Mark Vink and many others have exposed the PACE trial as deeply flawed, and potentially fraudulent, and many others have analyzed and reported on the significant harms and ethical issues resulting from the use of CBT or GET in patients with ME/CFS.[11][12][9][13][14][2]

The UK Parliament House of Lords PACE Trial debate 6th February 2013 and the UK Parliament Grand Committee Room debate 21st June 2018 debated the PACE trial. Carol Monaghan MP for the Scottish National Party stated at a February 20th debate in the House of Commons Hansard, “I think that when the full details of the trial become known, it will be considered one of the biggest medical scandals of the 21st century.”[15][16]

Notable studies[edit | edit source]

- 1977, The Need for a New Medical Model: A Challenge for Biomedicine[7] (Abstract)

- 1989, Management of chronic (post-viral) fatigue syndrome[17] (Full text)

- 1998, The Persistence of Fatigue in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Multiple Sclerosis: The Development of a Model[4] (Abstract)

- 2005, A population-based study of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) experienced in differing patient groups: An effort to replicate Vercoulen et al.'s model of CFS[8] (Full text)

- 2009, A review on cognitive behavorial therapy (CBT) and graded exercise therapy (GET) in myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) / chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS): CBT/GET is not only ineffective and not evidence-based, but also potentially harmful for many patients with ME/CFS[9] (Abstract)

- 2010, Chronic fatigue syndrome: Harvey and Wessely's (bio) psychosocial model versus a bio (psychosocial) model based on inflammatory and oxidative and nitrosative stress[5] (Full text)

- 2011, Health-related quality of life in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: group cognitive behavioural therapy and graded exercise versus usual treatment. A randomised controlled trial with 1 year of follow-up[18] (Full text)

- 2016, 'Blaming the victim, all over again: Waddell and Aylward’s biopsychosocial (BPS) model of disability'[19] (Full text)

- 2016, 'Chronic fatigue syndrome: is the biopsychosocial model responsible for patient dissatisfaction and harm?[13] (Abstract)

- 2017, Contesting the psychiatric framing of ME/CFS[20] (Full text)

- 2018, 'Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and the biopsychosocial model: a review of patient harm and distress in the medical encounter'[14] (Abstract)

- 2019, The ‘cognitive behavioural model’ of chronic fatigue syndrome: Critique of a flawed model[2] (Full text)

See also[edit | edit source]

- Cognitive behavioral model (the 3Ps model)

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

- Ethical issues

- Graded exercise therapy

- Medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS)

- Music therapy

- PACE trial

- Psychologization | last4

- UK Parliament House of Lords PACE Trial debate 6th February 2013

- UK Parliament Grand Committee Room debate 21st June 2018

- UK Parliament Commons Chamber debate 24th January 2019

- Wessely school

Learn more[edit | edit source]

- Notes on the Ineffectiveness of the Biopsychosocial Model for Treating Myalgic Encephalomyelitis[10] - Invest in ME Research

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Mitchell, Gina. "What is the Biopsychosocial Model? - Definition & Example - Video & Lesson Transcript | Study.com". Oxford University. Chapter 4 Lesson 15. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Geraghty, Keith; Jason, Leonard; Sunnquist, Madison; Tuller, David; Blease, Charlotte; Adeniji, Charles (January 1, 2019). "The 'cognitive behavioural model' of chronic fatigue syndrome: Critique of a flawed model". Health Psychology Open. 6 (1): 2055102919838907. doi:10.1177/2055102919838907. ISSN 2055-1029.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 White, Peter, ed. (2005). Biopsychosocial medicine: an integrated approach to understanding illness (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198530331.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Vercoulen, J.H. M.M.; Swanink, C.M. A; Galama, J. M. D; Fennis, J. F. M; Jongen, P. J. H; Hommes, O. R; van der Meer, J.W.M; Bleijenberg, G (December 1, 1998). "The persistence of fatigue in chronic fatigue syndrome and multiple sclerosis: Development of a model". Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 45 (6): 507–517. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(98)00023-3. ISSN 0022-3999.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Maes, Michael; Twisk, Frank NM (June 15, 2010). "Chronic fatigue syndrome: Harvey and Wessely's (bio)psychosocial model versus a bio(psychosocial) model based on inflammatory and oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways". BMC Medicine. 8 (1): 35. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-8-35. ISSN 1741-7015.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Harvey, Samuel B.; Wessely, Simon (October 12, 2009). "Chronic fatigue syndrome: identifying zebras amongst the horses". BMC medicine. 7: 58. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-7-58. ISSN 1741-7015. PMC 2766380. PMID 19818158.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Engel, George L. (1977). "The Need for a New Medical Model: A Challenge for Biomedicine". Science. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Song, Sharon; Jason, Leonard A (June 2005). "A population-based study of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) experienced in differing patient groups: An effort to replicate Vercoulen et al.'s model of CFS" (PDF). Journal of Mental Health. 14 (3): 277–289. doi:10.1080/09638230500076165. ISSN 0963-8237.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Twisk, Frank N.M.; Maes, Michael (2009). "A review on cognitive behavorial therapy (CBT) and graded exercise therapy (GET) in myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) / chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS): CBT/GET is not only ineffective and not evidence-based, but also potentially harmful for many patients with ME/CFS". Neuro Endocrinology Letters. 30 (3): 284–299. ISSN 0172-780X. PMID 19855350.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Invest in ME Research. "Notes on the Ineffectiveness of the Biopsychosocial Model for Treating Myalgic Encephalomyelitis" (PDF). Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- ↑ Vink, Mark (2017). "Assessment of Individual PACE Trial Data in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Cognitive Behavioual Therapy and Graded Exercise Therapy are Ineffective, Do Not Lead to Actual Recovery and Negative Outcomes may be Higher than Reported". J Neuro Neurobiol. 3 (1). doi:10.16966/2379-7150.136.

- ↑ Vink, Mark (2016). "The PACE Trial Invalidates the Use of Cognitive Behavioral and Graded Exercise Therapy in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Review". Journal of Neurology and Neurobiology. 2 (3). doi:10.16966/2379-7150.124. ISSN 2379-7150.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Geraghty, Keith J.; Esmail, Aneez (August 1, 2016). "Chronic fatigue syndrome: is the biopsychosocial model responsible for patient dissatisfaction and harm?". Br J Gen Pract. 66 (649): 437–438. doi:10.3399/bjgp16X686473. ISSN 0960-1643. PMID 27481982.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Geraghty, Keith J.; Blease, Charlotte (June 21, 2018). "Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and the biopsychosocial model: a review of patient harm and distress in the medical encounter". Disability and Rehabilitation: 1–10. doi:10.1080/09638288.2018.1481149. ISSN 0963-8288.

- ↑ Tuller, David (March 28, 2018). "Trial By Error: A Q-and-A with Scottish MP Carol Monaghan". Virology blog. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- ↑ "PACE Trial: People with ME - Hansard". hansard.parliament.uk (Volume 636 ed.). February 20, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- ↑ Wessely, S.; David, A.; Butler, S.; Chalder, T. (January 1989). "Management of chronic (post-viral) fatigue syndrome". The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 39 (318): 26–29. ISSN 0035-8797. PMC 1711569. PMID 2553945.

- ↑ Núñez, Montserrat; Fernández-Solà, Joaquim; Nuñez, Esther; Fernández-Huerta, José-Manuel; Godás-Sieso, Teresa; Gomez-Gil, Esther (March 2011). "Health-related quality of life in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: group cognitive behavioural therapy and graded exercise versus usual treatment. A randomised controlled trial with 1 year of follow-up". Clinical Rheumatology. 30 (3): 381–389. doi:10.1007/s10067-010-1677-y. ISSN 1434-9949. PMID 21234629.

- ↑ Shakespeare, Tom; Watson, Nicholas; Alghaib, Ola Abu (February 1, 2017). "Blaming the victim, all over again: Waddell and Aylward's biopsychosocial (BPS) model of disability". Critical Social Policy. 37 (1): 22–41. doi:10.1177/0261018316649120. ISSN 0261-0183.

- ↑ Spandler, Helen; Allen, Meg (August 16, 2017). "Contesting the psychiatric framing of ME/CFS" (PDF). Social Theory & Health. 16 (2): 127–141. doi:10.1057/s41285-017-0047-0. ISSN 1477-8211.