Exercise

Exercise is any movement or physical activity considered to contribute to general health and well-being. Exercise may be recommended as part of a wellness regimen in any chronic illness.[1][2] However, exercise intolerance is a central feature of ME/CFS,[3] and patients show multiple documented abnormal responses to exercise, including significant worsening of all symptoms; this is the opposite response to how healthy people respond to exercise.[4] Rather than increase health and well-being, evidence from ME/CFS patients shows that exercise or even increased activity significantly reduces their physical and mental capacity over time, sometimes permanently.[5]

Worsening of symptoms due to exercise in ME/CFS patients cannot be explained by deconditioning (lack of fitness), or by psychological theories like "symptom focusing" or catastrophizing; the effects of exercise or over-exertion in patients include increased immune system symptoms, an increase in inflammatory markers in the blood, increased lactate in blood plasma, an increase in lactic acid in the muscles, and oxidative damage to DNA.[6]

Physiological effects of exercise

Exercise causes a variety of temporary physiological changes in healthy people. This includes an increase in respiratory rate, heart rate, and blood pressure in order to keep up with higher energy demands.[7] The chemical reactions that break down nutrients -- glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and the electron transport chain -- move more rapidly to liberate energy, and blood flow to muscles should increase. In healthy individuals, the amount of oxygen and carbon dioxide present in the blood should not alter significantly.[7]

Immune system

In healthy people, exercise induces a variety of temporary changes to immune markers. Immediately after exercise, natural killer cell activity is decreased and Leukotriene B4 (LTB4) increase, along with the LTB4/PGE2 ratio. Exercise elevates levels of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) for up to five days.[8]

Infection

Several studies of a mouse model of Coxsackie B3 myocarditis have found that exercise increases the virulence of the infection and results in poorer outcomes.[9][10][11][12][13]

Neurotransmitters

Acetylcholine, an important neurotransmitter that regulates immune response and muscle strength, decreases during exercise.

Effects of exercise in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

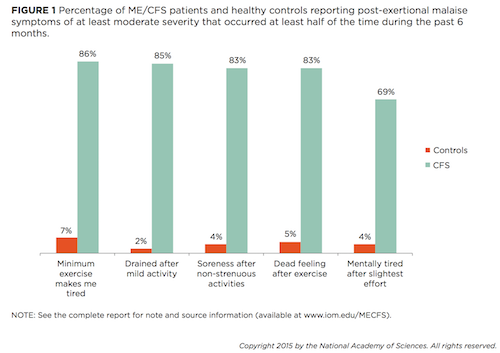

Post Exertional Malaise

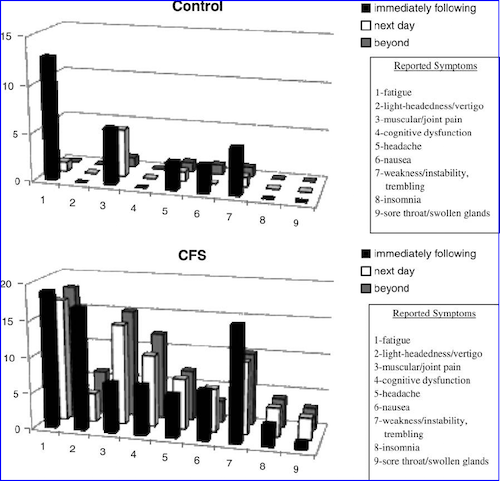

ME patients who exercise are likely to experience Post-exertional malaise, a worsening of symptoms following physical, cognitive, or sensory exertion.

Pain threshold

Pain thresholds, or the point at which a stimulus becomes painful, drop in people with CFS (as per the Fukuda criteria) after graded exercise. In healthy controls, pain thresholds rise. This phenomenon has been attributed to a dysfunction of the central anti-nociceptive mechanism in CFS patients.[14]

Immune System

Histamine, a chemical that is released in response to cellular damage and inflammation, is released during exercise in healthy individuals. The histamine dilates blood vessels in order to deliver nutrients to working muscles.[15] However, patients with ME may experience increased histamine release due to increased mast cell populations at baseline.[16]

Microbiome

A small study of ten CFS patients found significant changes in the composition of the microbiome and increased bacterial translocation (movement from the intestine into the bloodstream) following exercise. The study found increased Clostridium in the blood fifteen minutes after exercise and increased Bacilli 48 hours later.[17]

Musculature

Exercise has also been found to induce both early and excessive lactic acid formation in the muscles[18] with reduced intracellular concentrations of ATP and acceleration of glycolysis.[19] Several studies have found abnormal increases in plasma lactate following short period of moderate exercise that cannot be explained by deconditioning.[20] There are abnormalities in pH handling by peripheral muscle, and possible evidence of an increased acidosis and lactate accumulation.[21] [22][23]

There is also evidence of loss of capacity to recover from acidosis on repeat exercise, as demonstrated by the Two-Day Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test.[22]

Finally, there is evidence of abnormalities of AMPK activation and glucose uptake in cultured skeletal muscle cells in ME/CFS patients.[24]

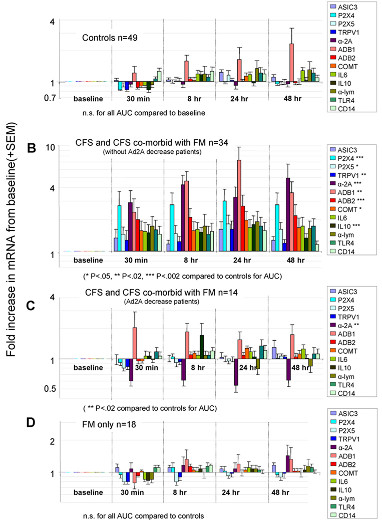

Gene expression

There is evidence of increased expression of certain genes following muscular exertion.[25] [26][27] A 2011 study found that moderate exercise in CFS increased the expression of 13 genes (sensory, adrenergic and 1 cytokine) for 48 hours, and the increases correlated with fatigue and pain levels (see graph).[26]

Second day exercise test

The seminal study on the response of chronic fatigue syndrome patients to a two-day cardiopulmonary exercise test was published by Mark VanNess, Christopher Snell and Staci Stevens in 2007: "Diminished Cardiopulmonary Capacity During Post-Exertional Malaise".[28] While people with CFS responded similarly to healthy controls on a first test, on a follow-up 24 hours later, they were unable to replicate their original normal results. Instead, they had significantly lower values for VO2 peak and AT; these differences could be used to identify the CFS patient over 90% of the time. A repeat study in 2013 confirmed these results.[29]

In a confirmation study, Doctor Betsy Keller also found that patients could not repeat their performance on a second cardiopulmonary exercise test performed a day after the first.[30]

A review by Nijs et al. found that multiple studies showed reduced peak heart rate, reduced endurance, reduced peak work rate, reduced peak oxygen uptake, lower blood lactate values, and an increased respiratory exchange ratio in people with ME, ME/CFS, or CFS; see Oxidative impairment.[31]

It is important to note that CPET testing oxygen uptake (VO2), carbon dioxide output (VCO2), tidal volume (VT), blood pressure, and oxygen saturation are objective measures, and cannot be invalidated with inadequate effort.

Oxidative impairment

DeBecker et al (2000) and VanNess et al (2003) found low VO2 during exercise testing;[32][33] Fulle et al. (2000) demonstrated oxidative damage to DNA[6]; and Wong et al. (1992) showed defects in oxidative metabolism and poor recovery of ATP after exercise.[34]

Graded exercise therapy

Graded exercise therapy involves incremental increases in physical activity or exercise over time, is a controversial treatment for ME/CFS, due to exercise intolerance being a central feature of the disease.

Excessive exercise

Excessive exercise in healthy people, particularly athletes, is known to cause overtraining syndrome, which is typically recognized by unexplained decreased exercise capacity in combination with other symptoms.[35][36] Overtraining syndrome, while commonly fatiguing, has different signs and symptoms than CFS,[3][35][37] and effects of overtraining should not be confused with ME/CFS,[38] which is a multi-systemic neurological disease with a different symptom profile, involves multiple processes including mitochondria dysfunction, neuroinflammation, and abnormal immune system responses to exercise, and has no known cure or established treatment.[39][3] ME/CFS cannot be diagnosed when symptoms may be the result of excessive exertion, for example prolonged or intense exercise, or when there is inadequate nutrition, and the most widely used diagnostic criteria also requires 6 months of symptoms before diagnosis.[3][40][37]

Exercise in other chronic illnesses

Exercise and increased physical activity is increasingly being promoted and encouraged for patients with chronic diseases[41] due to the positive effects found in a considerable number of different chronic illnesses and diseases, including:

- psychiatric diseases:

- neurological diseases:

- dementia

- multiple sclerosis - although a temporary worsening of symptoms is common

- Parkinson's disease

- metabolic diseases:

- diabetes (both types 1 and 2) - although it should be avoided or modified in some circumstances

- hyperlipidemia

- metabolic syndrome

- obesity

- polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS)

- cardiovascular diseases:

- cerebral apoplexy (stroke, cerebrovascular accident, apoplexy)

- claudication intermittent

- coronary heart disease - only if unstable angina are certain other conditions are not present, high-intensity workouts should be avoided

- heart failure - only if certain conditions are met

- high blood pressure - high-intensity workouts should be avoided and medication may be needed to reduce blood pressure first

- pulmonary (respiratory) diseases:

- asthma - if no infection is present and it does not cause severe exacerbation of asthma

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) - oxygen may be needed during exercise

- cystic fibrosis - if no infection is present

- musculoskeletal disorders:

- back pain - only if no event fracture is suspected, and with certain conditions

- cancer - under certain conditions and with supervision

- osteoarthritis - under certain conditions

- osteoporosis - exercise should not involve risk of a fall

- rheumatoid arthritis[42] - under certain conditions and with supervision

Regular exercise has general benefits in chronically ill people without ME/CFS depend on doing the correct type and intensity of physical activity for the illness in order to avoid aggravating symptoms; if done correctly these include

- reduced risk of falls and fractures

- reduced risk of additional chronic diseases

- reduced depression, especially for people medically ill with mild or moderate depression

- reduced pain in certain conditions, particularly musculoskeletal or pain conditions, if the most appropriate type and intensity of physical activity is used.[43][44]

Talks and interviews

- 2009, [1]Staci Stevens speaking to CFSAC meeting

- 2010, Slide presentation to CFSAC by Staci Stevens, CFSAC

- 2012, Clinical exercise testing in CFS/ME research and treatment - Christopher Snell

- 2012, MECFS Alert Episode 32 - Staci Stevens, Director of the Pacific Fatigue Lab, ME/CFS Alert

- 2012, Top 10 Things You Should Know About Post-Exertional Relapse - Staci Stevens

- 2013, CFS gene expression after exercise (part 1) - Lucinda Bateman

- 2014, Exercise and ME/CFS, Part 1 - Mark VanNess at Bristol Watershed

- 2015, 72. Gene-expression and exercise / Gen-expressie en inspanning[45] – Dr. Lucinda Bateman, Science for Patients)

- 2016, Expanding Physical Capability in ME/CFS. Part 1 of 2. Dr. Mark VanNess

- 2016, Expanding Physical Capability in ME/CFS. Part 2 of 2. - Mark VanNess

Notable studies

- 2000, The Differential Diagnosis and Clinical Approach to the Athlete With Chronic Fatigue[37]

- 2011, PACE trial

- 2011, Tired of being inactive: a systematic literature review of physical activity, physiological exercise capacity and muscle strength in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome[46] (Abstract)

- 2016, Effect of Acute Exercise on Fatigue in People with ME/CFS/SEID: A Meta-analysis

- 2016, Cochrane meta-analysis

- 2017, Neural consequences of post-exertion malaise in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome[4]

- 2020, Prediction of Discontinuation of Structured Exercise Programme in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Patient[47] - (Full text)

Learn more

- 2011 - ME/CFS and Exercise: The VO2 Max Based Exercise Program, A Personal View by Dan Moricoli

- 2011 - Loss of capacity to recover from acidosis on repeat exercise in chronic fatigue syndrome: a case–control study, an essay for ME Research UK

- 2014 - ME/CFS and Exercise: VO2 Max Testing with Nancy Klimas M.D. - PREVIEW (this is a preview of a pay-per-view video)

- 2014 - Sufferers of chronic fatigue, fibromyalgia have hope in new diagnostic tool by Wendy Leonard for Deseret News

- 2015 - Dr. VanNess on recent press reports by Sally Burch in Just ME blog

- 2015 - Deviant Cellular and Physiological Responses to Exercise in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome by Frank N.M. Twisk, and Keith J. Geraghty[48]

- 2015 - Objective Evidence of Post-exertional “Malaise” in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome by Frank N.M. Twisk

- 2015 - Exercise alteration of the CFS Microbiome from CFS Remission blog

- Jan 2016 - Review Article: Understanding Muscle Dysfunction in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome by Gina Rutherford, Philip Manning, and Julia L. Newton[49]

- Feb 10, 2016 - Lost in Translation - The ME-Polio Connection and the Dangers of Exercise by Nancy Blake for ProHealth

- Jul 2016 - Australian metabolomics study of young women with ME/CFS (CCC) by Sasha Nimmo for ME Australia

- Aug 2016 - Neuromuscular Strain in ME/CFS – Research Study Conclusion in Solve ME/CFS Initiative Newsletter

- Oct 2017 - For People With Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, More Exercise Isn't Better - Michaeleen Doucleff, Shots: Health News From NPR

See also

- Two-day cardiopulmonary exercise test

- Graded exercise therapy

- Burnout

- Delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS)

- Muscle fatigability

- Mitochondrion

- Deconditioning

- Post-exertional malaise

- Glass ceiling effect

- Strength Training

References

- ↑ Pederson, B.K.; Saltin, B. (2006). "Evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in chronic disease" (PDF). Scand J Med Sci Sports. 16 (Suppl 1): 3–63.

- ↑ Hovanec, Nina; Bellemore, Derek; Kuhnow, Jason; Miller, Felicia; van Vloten, Alexi; Vandervoort, Anthony A. (March 3, 2015). "Exercise Prescription Considerations for Individuals with Multiple Chronic Diseases: Systematic Review". J Gerontol Geriatr Res. 4 (201).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Symptoms of ME/CFS | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)". cdc.gov. February 9, 2021. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Cook, Dane B.; Light, Alan R.; Light, Kathleen C.; Broderick, Gordon; Shields, Morgan R.; Dougherty, Ryan J.; Meyer, JacobD.; VanRiper, Stephanie; Stegner, Aaron J. (May 1, 2017). "Neural consequences of post-exertion malaise in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 62: 87–99. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2017.02.009. ISSN 0889-1591.

- ↑ ME Association (May 2015). "ME Association illness management report: no decisions about me without me" (PDF). ME Association. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Fulle, S; Mecocci, P; Fanó, G; Vecchiet, I; Vecchini, A; Racciotti, D; Cherubini, A; Pizzigallo, E; Vecchiet, L; Senin, U; Beal, MF (December 15, 2000), "Specific oxidative alterations in vastus lateralis muscle of patients with the diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome", Free Radical Biology & Medicine, 29 (12): 1252–1259, doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00419-6, ISSN 0891-5849, PMID 11118815

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Burton, Deborah Anne; Stokes, Keith; Hall, George M (December 1, 2004). "Physiological effects of exercise". Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain. 4 (6): 185–8 – via BJA Education.

- ↑ Gray, J B; Martinovic, A M (July 1994), "Eicosanoids and essential fatty acid modulation in chronic disease and the chronic fatigue syndrome", Medical Hypotheses, 43 (1): 31–42, doi:10.1016/0306-9877(94)90046-9, PMID 7968718

- ↑ Cabinian AE, Kiel RJ, Smith F, Ho KL, Khatib R, Reyes MR. Modification of exercise-aggravated coxsackie virus B3 murine myocarditis by T-lymphocyte suppression in an inbred model. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1990; 115: 454– 62.

- ↑ Kiel RJ, Smith FE, Chason J, Khatib R, Reyes MD. Coxsackie B3 myocarditis in C3H/HeJ mice: Description of an inbred model and the effect of exercise on the virulence. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1989; 5: 248– 67.

- ↑ Ilbäck, NG (June 1989). "Exercise in coxsackie B3 myocarditis: Effects on heart lymphocyte subpopulations and the inflammatory reaction". American Heart Journal. 117: 1298–302.

- ↑ Gatmaitan, Bienvenido (June 1, 1970). "Augmentation of the Virulence of Murine Coxsackie Virus B-3 Myocardiopathy by Exercise". Journal of Experimental Medicine. 131: 1121.

- ↑ Reyes, MP (February 1976). "Interferon and neutralizing antibody in sera of exercised mice with coxsackievirus B-3 myocarditis". Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 151: 333–8.

- ↑ Whiteside, Alan; Hansen, Stig; Chaudhuri, Abhijit (2004), "Exercise lowers pain threshold in chronic fatigue syndrome", Pain, 109 (3): 497-9, doi:10.1016/j.pain.2004.02.029, PMID 15157711

- ↑ Romero, S.A.; Hocker, A.D.; Mangum, J.E.; Luttrell, M.J.; Turnbull, D.W.; Halliwill, J.R.; Struck, A.J.; Ely, M.R.; Sieck, D.C.; Dreyer, H.C.; Halliwill, J.R (2016). "Evidence of a broad histamine footprint on the human exercise transcriptome". The Journal of Physiology. 594 (17): 5009–5023.

- ↑ Rönnberg, E; Calounova, G; Pejler, G (June 2017). "Novel characterisation of mast cell phenotypes from peripheral blood mononuclear cells in chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis patients". Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 35 (2): 75–81.

- ↑ Shukla, Sanjay K; Cook, Dane; Meyer, Jacob; Vernon, Suzanne D; Le, Thao; Clevidence, Derek; Robertson, Charles E; Schrodi, Steven J; Yale, Steven; Frank, Daniel N (December 18, 2015), "Changes in Gut and Plasma Microbiome following Exercise Challenge in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)", PLoS ONE, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0145453, PMID 26683192

- ↑ Plioplys, AV; Plioplys, S (1995), "Serum levels of carnitine in chronic fatigue syndrome: clinical correlates", Neuropsychobiology, 32 (3): 132-138, PMID 8544970

- ↑ McCully, KK; Natelson, BH; Iotti, S; Sisto, S; Leigh, JS Jr. (May 1996), "Reduced oxidative muscle metabolism in chronic fatigue syndrome", Muscle Nerve, 19 (5): 621-625, PMID 8618560

- ↑ Lane, R J; Barrett, M C; Taylor, D J; Kemp, G J; Lodi, R (May 1998), "Heterogeneity in chronic fatigue syndrome: evidence from magnetic resonance spectroscopy of muscle", Neuromuscul Disord, 8 (3–4): 204-9, PMID 9631403

- ↑ Jones, David EJ; Hollingsworth, Kieren G; Taylor, Renee R; Blamire, Andrew M; Newton, Julia L (April 2010), "Abnormalities in pH handling by peripheral muscle and potential regulation by the autonomic nervous system in chronic fatigue syndrome", J Intern Med, 267 (4): 394-401, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02160.x, PMID 20433583

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Jones, David EJ; Hollingsworth, Kieren G; Jakovljevic, Djordje G; Fattakhova, Gulnar; Pairman, Jessie; Blamire, Andrew M; Trenell, Michael I; Newton, Julia L (July 12, 2011), "Loss of capacity to recover from acidosis on repeat exercise in chronic fatigue syndrome", Eur J Clin Invest, 42 (2): 186-94, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2011.02567.x, PMID 21749371

- ↑ Lengert, Nicor; Drossel, Barbara (July 2015), "In silico analysis of exercise intolerance in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome", Biophysical Chemistry, 202: 21–31, doi:10.1016/j.bpc.2015.03.009, PMID 25899994

- ↑ Brown, Audrey E; Jones, David E; Walker, Mark; Newton, Julia L (April 2, 2015), "Abnormalities of AMPK activation and glucose uptake in cultured skeletal muscle cells", PLoS One, 10 (4), doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0122982, PMID 25836975

- ↑ Light, Alan R; White, Andrea T; Hughen, Ronald W; Light, Kathleen C (July 31, 2009), "Moderate exercise increases expression for sensory, adrenergic, and immune genes in chronic fatigue syndrome patients but not in normal subjects", J Pain, 10 (10): 1099-112, doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2009.06.003, PMID 19647494

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Light, Alan R; Bateman, Lucinda; Jo, Daehyun; Hughen, Ronald W; Vanhaitsma, TA; White, Andrea T; Light, Kathleen C (July 13, 2011), "Gene expression alterations at baseline and following moderate exercise in patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Fibromyalgia Syndrome", J Intern Med, 271 (1): 64-81, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02405.x, PMID 21615807

- ↑ White, Andrea T; Light, Alan R; Hughen, Ronald W; VanHaitsma, Timothy A; Light, Kathleen C (December 30, 2011), "Differences in metabolite-detecting, adrenergic, and immune gene expression after moderate exercise in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, patients with multiple sclerosis, and healthy controls", Psychosom Med, 74 (1): 46-54, doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e31824152ed, PMID 22210239

- ↑ VanNess, J Mark; Snell, Christopher R; Stevens, Staci R (2007), "Diminished Cardiopulmonary Capacity During Post-Exertional Malaise", Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, 14 (2): 77-85, doi:10.1300/J092v14n02_07

- ↑ Snell, Christopher R; Stevens, Staci R; Davenport, Todd E; VanNess, J Mark (October 31, 2013), "Discriminative Validity of Metabolic and Workload Measurements for Identifying People With Chronic Fatigue Syndrome", Physical Therapy (APTA), 93 (11): 1484-1492, doi:10.2522/ptj.20110368, PMID 23813081

- ↑ Keller, Betsy A; Pryor, John Luke; Giloteaux, Ludovic (April 23, 2014), "Inability of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients to reproduce VO₂peak indicates functional impairment", J Transl Med (12): 104, doi:10.1186/1479-5876-12-104, PMID 24755065

- ↑ Nijs, J; Nees, A; Paul, L; De Kooning, M; Ickmans, K; Meeus, M; Van Oosterwijck, J (2014), "Altered immune response to exercise in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a systematic literature review" (PDF), Exercise Immunology Review (20): 94-116, PMID 24974723

- ↑ De Becker, P; Roeykens, J; Reynders, M; McGregor, N; De Meirleir, K (November 27, 2000), "Exercise capacity in chronic fatigue syndrome", Archives of Internal Medicine, 160 (21): 3270–3277, doi:10.1001/archinte.160.21.3270, ISSN 0003-9926, PMID 11088089

- ↑ VanNess, JM; Snell, CR; Strayer, DR; Dempsey, L; Stevens, SR (June 2003), "Subclassifying chronic fatigue syndrome through exercise testing" (PDF), Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 35 (6): 908–913, doi:10.1249/01.MSS.0000069510.58763.E8, ISSN 0195-9131, PMID 12783037

- ↑ Wong, R; Lopaschuk, G; Zhu, G; Walker, D; Catellier, D; Burton, D; Teo, K; Collins-Nakai, R; Montague, T (December 1992), "Skeletal muscle metabolism in the chronic fatigue syndrome. In vivo assessment by 31P nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy", Chest, 102 (6): 1716–1722, doi:10.1378/chest.102.6.1716, ISSN 0012-3692, PMID 1446478

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Meeusen, Romain; Duclos, Martine; Foster, Carl; Fry, Andrew; Gleeson, Michael; Nieman, David; Raglin, John; Rietjens, Gerard; Steinacker, Jürgen (January 1, 2013). "Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of the overtraining syndrome: Joint consensus statement of the European College of Sport Science (ECSS) and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM)". European Journal of Sport Science. 13 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1080/17461391.2012.730061. ISSN 1746-1391.

- ↑ Kreher, Jeffrey; Schwartz, Jennifer B. (2012). "Overtraining Syndrome: A practical guide". SAGE Journals. 4 (2): 128–138. doi:10.1177/1941738111434406. PMC 3435910. PMID 23016079. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Lambert, M.I.; Derman, W.E. (January 1, 2000). "The differential diagnosis and clinical approach to the athlete with chronic fatigue" (PDF). International SportMed Journal. 1 (3). ISSN 1528-3356.

- ↑ Mommersteeg, Paula M.C.; Heijnen, Cobi J.; Verbraak, Marc J.P.M.; van Doornen, Lorenz J.P. (February 1, 2006). "Clinical burnout is not reflected in the cortisol awakening response, the day-curve or the response to a low-dose dexamethasone suppression test". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 31 (2): 216–225. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.07.003. ISSN 0306-4530.

- ↑ Carruthers, BM; van de Sande, MI; De Meirleir, KL; Klimas, NG; Broderick, G; Mitchell, T; Staines, D; Powles, ACP; Speight, N; Vallings, R; Bateman, L; Bell, DS; Carlo-Stella, N; Chia, J; Darragh, A; Gerken, A; Jo, D; Lewis, DP; Light, AR; Light, KC; Marshall-Gradisnik, S; McLaren-Howard, J; Mena, I; Miwa, K; Murovska, M; Stevens, SR (2012), Myalgic encephalomyelitis: Adult & Paediatric: International Consensus Primer for Medical Practitioners (PDF), ISBN 978-0-9739335-3-6

- ↑ Spence, Vance. "Snippets | A presentation by MERGE Chairman Dr Vance Spence on 12 November 2005 at the Oak Tree Court Conference Centre, Coventry, at the invitation of the Warwickshire Network for ME". Irish M.E. Association.

- ↑ McNally, S. (2015), "Exercise: The miracle cure and the role of the doctor in promoting it" (PDF), Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, London

- ↑ Pedersen, B.K.; Saltin, B. (December 2015). "Exercise as medicine - evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases". Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 25: 1–72. doi:10.1111/sms.12581.

- ↑ Gloth, Mark J.; Matesi, Ann M. (September 1, 2001). "Physical therapy and exercise in pain management". Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 17 (3): 525–535. doi:10.1016/S0749-0690(05)70084-7. ISSN 0749-0690.

- ↑ Kujala, U.M. (January 1, 2006). "Benefits of exercise therapy for chronic diseases". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 40 (1): 3–4. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2005.021717. ISSN 0306-3674. PMC 2491939. PMID 16371482.

- ↑ Bateman, Lucinda (November 3, 2015), "Video interview: Gene-expression and exercise", Wetenschap voor Patienten - ME/cvs Vereniging

- ↑ Nijs, Jo; Aelbrecht, Senne; Meeus, Mira; Van Oosterwijck, Jessica; Zinzen, Evert; Clarys, Peter (2011). "Tired of being inactive: a systematic literature review of physical activity, physiological exercise capacity and muscle strength in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome" (PDF). Disability and Rehabilitation. 33 (17–18): 1493–1500. doi:10.3109/09638288.2010.541543. ISSN 1464-5165. PMID 21166613.

- ↑ Kujawski, Sławomir; Cossington, Jo; Słomko, Joanna; Dawes, Helen; Strong, James W.L.; Estevez-Lopez, Fernando; Murovska, Modra; Newton, Julia L.; Hodges, Lynette (October 26, 2020). "Prediction of Discontinuation of Structured Exercise Programme in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Patients". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 9 (11): 3436. doi:10.3390/jcm9113436. ISSN 2077-0383. PMC 7693605. PMID 33114704.

- ↑ Twisk, Frank NM; Geraghty, Keith J (July 11, 2015), "Deviant Cellular and Physiological Responses to Exercise in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome" (PDF), Jacobs Journal of Physiology, 1 (2): 007

- ↑ Rutherford, Gina; Manning, Philip; Newton, Julia L (January 13, 2016), "Review Article: Understanding Muscle Dysfunction in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome", Journal of Aging Research, 2016 (4): 1–13, doi:10.1155/2016/2497348, PMID 26998359