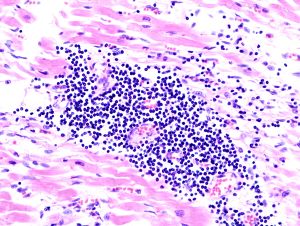

Myocarditis

Myocarditis or inflammatory cardiomyopathy is an inflammation of the heart muscle.[1] Myocarditis can be caused by numerous toxic or infectious agents, including viruses, bacteria, fungal infections, or by autoimmune disease or a chest infection.[2]

Coxsackievirus B3 has been found in 20-25% of patients with cardiomyopathy and myocarditis.[3][4][5][6] In mouse models, Ampligen was found to be protective of Coxsackie B3-induced myocarditis.[7]

More recently, myocarditis has been found in people who have recovered from COVID-19, including some people who were mildly ill or asymptomatic, including professional athletes.[8] Myocarditis treatment varies from monitoring to anti-inflammatories, antibiotics and more intensive treatments.[2] It is a significant cause of sudden cardiac death in professional athletes.[9] Expert consensus advice has been published for competitive athletes who have tested positive for COVID-19.[9]

Several studies of a mouse model of Coxsackie B3 myocarditis have found that exercise increases the virulence of the infection and results in poorer outcomes.[10][11][12][13][14]

Signs and symptoms[edit | edit source]

Common myocarditis symptoms include:

- shortness of breath, particularly during gentle exercise or walking

- stabbing pain or tightness in the chest, which may spread across the body

- flu-like symptoms including a high temperature, tiredness and fatigue

- heart palpitations or an abnormal heart rhythm.[2]

Many of these symptoms are also found in people with ME/CFS who do not have myocarditis.[15]

Notable studies[edit | edit source]

- Oct 26, 2020, Coronavirus Disease 2019 and the Athletic Heart. Emerging Perspectives on Pathology, Risks, and Return to Play[8] - (Full text)

News articles, letters and blogs[edit | edit source]

- Aug 2020, COVID-19 Can Wreck Your Heart, Even if You Haven’t Had Any Symptoms - Scientific American

- Sep 11, 2020, A closer look at COVID-19 and heart complications among athletes - Genaro C. Armas, American Heart Association News

- Sep 11, 2020, Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Findings in Competitive Athletes Recovering From COVID-19 Infection[9] - Saurabh Rajpal, Matthew S. Tong, James Borchers, Karolina M. Zareba, Timothy P. Obarski, Orlando P. Simonetti, Curt J. Daniels. JAMA Cardiology.

Learn more[edit | edit source]

See also[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ "Myocarditis". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 British Heart Foundation. "Myocarditis". Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ↑ Tracy S, Chapman NM, McManus BM, Pallansch MA, Beck MA, et al. (1990) A molecular and serologic evaluation of enteroviral involvement in human myocarditis. J Mol Cell Cardiol 22: 403–414.

- ↑ Bowles NE, Richardson PJ, Olsen EG, Archard LC (1986) Detection of Coxsackie-B-virus-specific RNA sequences in myocardial biopsy samples from patients with myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy. Lancet 1: 1120–1123.

- ↑ Martin AB, Webber S, Fricker FJ, Jaffe R, Demmler G, et al. (1994) Acute myocarditis. Rapid diagnosis by PCR in children. Circulation 90: 330–339.

- ↑ Jin O, Sole MJ, Butany JW, Chia WK, McLaughlin PR, et al. (1990) Detection of enterovirus RNA in myocardial biopsies from patients with myocarditis and cardiomyopathy using gene amplification by polymerase chain reaction. Circulation 82: 8–16.

- ↑ Padalko, E (January 2004). "The interferon inducer ampligen [poly(I)-poly(C12U)] markedly protects mice against coxsackie B3 virus-induced myocarditis". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 48: 267–74.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kim, Jonathan H.; Levine, Benjamin D.; Phelan, Dermot; Emery, Michael S.; Martinez, Mathew W.; Chung, Eugene H.; Thompson, Paul D.; Baggish, Aaron L. (October 26, 2020). "Coronavirus Disease 2019 and the Athletic Heart". JAMA Cardiology. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.5890. ISSN 2380-6583.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamacardiology/fullarticle/2770645

- ↑ Cabinian AE, Kiel RJ, Smith F, Ho KL, Khatib R, Reyes MR. Modification of exercise-aggravated coxsackie virus B3 murine myocarditis by T-lymphocyte suppression in an inbred model. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1990; 115: 454– 62.

- ↑ Kiel RJ, Smith FE, Chason J, Khatib R, Reyes MD. Coxsackie B3 myocarditis in C3H/HeJ mice: Description of an inbred model and the effect of exercise on the virulence. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1989; 5: 248– 67.

- ↑ Ilbäck, NG (June 1989). "Exercise in coxsackie B3 myocarditis: Effects on heart lymphocyte subpopulations and the inflammatory reaction". American Heart Journal. 117: 1298–302.

- ↑ Gatmaitan, Bienvenido (June 1, 1970). "Augmentation of the Virulence of Murine Coxsackie Virus B-3 Myocardiopathy by Exercise". Journal of Experimental Medicine. 131: 1121.

- ↑ Reyes, MP (February 1976). "Interferon and neutralizing antibody in sera of exercised mice with coxsackievirus B-3 myocarditis". Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 151: 333–8.

- ↑ Carruthers, BM; van de Sande, MI; De Meirleir, KL; Klimas, NG; Broderick, G; Mitchell, T; Staines, D; Powles, ACP; Speight, N; Vallings, R; Bateman, L; Bell, DS; Carlo-Stella, N; Chia, J; Darragh, A; Gerken, A; Jo, D; Lewis, DP; Light, AR; Light, KC; Marshall-Gradisnik, S; McLaren-Howard, J; Mena, I; Miwa, K; Murovska, M; Stevens, SR (2012), Myalgic encephalomyelitis: Adult & Paediatric: International Consensus Primer for Medical Practitioners (PDF), ISBN 978-0-9739335-3-6