The 3Ps model

This article is a stub. |

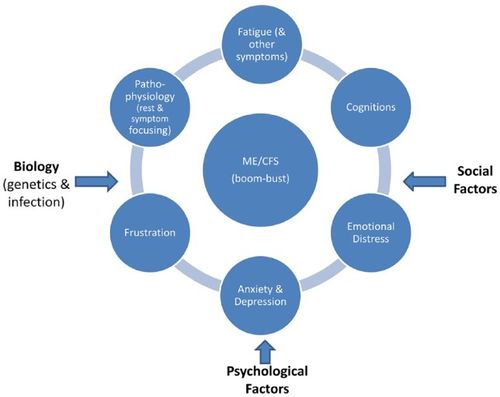

The 3Ps model or Cognitive Behavioral Model (CBM) of chronic fatigue syndrome is a theory that proposes that CFS can be explained by predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating factors.[1][2][3]

The 3Ps model is a biopsychosocial hypotheses, and has been used to justify the use of a form of psychotherapy called cognitive behavioral therapy in patients with ME/CFS, irrespective of whether a co-existing mental illness is present.

Source: Geraghty et al (2019). Health Psychology Open, 6(1), 2055102919838907. License: CC-BY-4.0

Wessely's CBM

Vercoulen's CBM

Predisposing factors

Precipitating factors

Perpetuating factors

Perpetuating or maintaining factors are hypothesized to be:

- kinesiophobia - phobia or fear of exercise that is not based on a realistic understanding of the illness

- deconditioning, meaning lack of fitness due to inactive

- excessive rest

- boom and bust activity cycle of doing too much on a good day, and too little on a bad day

The 3Ps model is based on a hypothesis of a vicious cycle that keeps the illness going - without perpetuating factors there would be nothing to keep the illness continuing... according to this theory there is no underlying disease and full recovery can be achieved by psychological and behavioral changes only - meaning that ME/CFS is considered fully curable through cognitive behavioral therapy and/or graded exercise therapy.

This vicious model holds the patient fully responsible for recovery, which can lead to negative outcomes, such as:

- assuming that ME/CFS is not a serious or dangerous illness even when severe - leading to medical neglect and abuse

- patient blaming when patients do not recover

- assuming that patients are physically well enough to fully follow a recovery program

- assuming that not following a recovery plan fully is due to psychological factors only, e.g., lack of motivation, presumed secondary gain, not wanting to recover, which can lead to removal of essential support

- clinicians fully accepting a hypothesis such as the 3Ps model can then assuming that a clinical trial testing the associated treatments must have successful outcomes - a significant bias that occurred in the FINE trial and the PACE trial

- psychologization

- medical gaslighting

- patient coercion instead of informed consent

Evidence

Song and Jason (2005) attempted to replicate Vercoulen's original CBM model, but were unable to fit the model to data collected from patients.[4]

The controversial PACE trial was the largest trial of cognitive behavioral therapy and graded exercise therapy, and was based on the cognitive behavioral model of chronic fatigue syndrome. Two of the three PACE trial principle investigators, Trudie Chalder and Michael Sharpe, were among the original authors of the CBM for CBT and both authored or co-authored books on the approach prior to the PACE trial. The PACE trial initially reported moderate improvements in symptoms, but a later Freedom of Information Act request provided crucial data that disputed this.[citation needed]

Criticism

The 3Ps model has been described as fundamentally flawed.[1]

Books

1989, Chronic Fatigue and its Syndromes[5]

Notable studies and articles

- 1989, Management of chronic (post-viral) fatigue syndrome[2] (Full text)

- 1998, The Persistence of Fatigue in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Multiple Sclerosis: The Development of a Model[6] (Abstract)

- 1995, Chronic fatigue syndrome: A cognitive approach[3] (Full text)

- 2005, A population-based study of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) experienced in differing patient groups: An effort to replicate Vercoulen et al.'s model of CFS[4] (Full text)

- 2019, The ‘cognitive behavioural model’ of chronic fatigue syndrome: Critique of a flawed model[1] (Full text)

Learn more

See also

- Biopsychosocial model

- Psychologization

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

- Graded exercise therapy

- PACE trial

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Geraghty, Keith; Jason, Leonard; Sunnquist, Madison; Tuller, David; Blease, Charlotte; Adeniji, Charles (January 1, 2019). "The 'cognitive behavioural model' of chronic fatigue syndrome: Critique of a flawed model". Health Psychology Open. 6 (1): 2055102919838907. doi:10.1177/2055102919838907. ISSN 2055-1029.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Chalder, T.; Butler, S.; David, A.; Wessely, S. (January 1989). "Management of chronic (post-viral) fatigue syndrome". The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 39 (318): 26–29. ISSN 0035-8797. PMID 2553945.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Surawy, Christina; Hackmann, Ann; Hawton, Keith; Sharpe, Michael (June 1, 1995). "Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A cognitive approach". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 33 (5): 535–544. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(94)00077-W. ISSN 0005-7967.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Song, Sharon; Jason, Leonard A (June 2005). "A population-based study of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) experienced in differing patient groups: An effort to replicate Vercoulen et al.'s model of CFS" (PDF). Journal of Mental Health. 14 (3): 277–289. doi:10.1080/09638230500076165. ISSN 0963-8237.

- ↑ Wessely, Simon; Hotopf, Matthew; Sharpe, Michael (1999). Chronic fatigue and its syndromes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192630469. OCLC 41028978.

- ↑ Vercoulen, J. H.M.M.; Swanink, C.M. A; Galama, J. M. D; Fennis, J. F. M; Jongen, P. J. H; Hommes, O. R; van der Meer, J.W.M; Bleijenberg, G (December 1, 1998). "The persistence of fatigue in chronic fatigue syndrome and multiple sclerosis: Development of a model". Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 45 (6): 507–517. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(98)00023-3. ISSN 0022-3999.