Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia or FM or fibromyalgia syndrome or FMS is a chronic, debilitating disorder characterized by widespread pain with additional symptoms such as cognitive dysfunction or "fibro fog", waking unrefreshed and fatigue.[1][2] Fibromyalgia is relatively common, affecting between 2-5% of the population.[3]

Brain imaging and neuroimaging studies have shown fibromyalgia to be a pain processing disorder involving altered pain processing in the central nervous system.[3] The pain and other symptoms of fibromyalgia appear to be caused by neurochemical imbalances in the central nervous system that lead to a "central amplification" of pain perception (Clauw et al., 2011).[3]

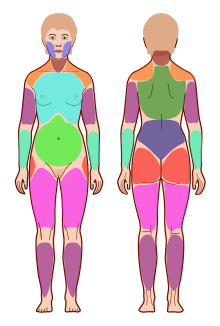

In fibromyalgia pain is widespread, on both sides of the body, and above and below the waist.[1][4]

Sufferers are fatigued (excessively tired) even after sleeping for long periods of time, and sleep is often disrupted by pain. Many FM sufferers have sleep disorders like sleep apnea and restless legs syndrome (RLS).[5][6][2] Cognitive impairment, when one cannot focus or pay attention and the patient has difficulty concentrating on mental tasks, is known by FM sufferers as "fibro fog".[5][6][2] Some people with fibromyalgia experience digestive system problems like irritable bowel syndrome or gastric-oesophagael reflux disease, depression, headaches or migraines, a painful bladder, or muscle cramps. Other symptoms may include tingling or numbness in hands and feet, pain in jaw and disorders of the jaw such as temporomandibular joint disorder (TMJ), and menstrual cycle cramps.[3][5][6][2]

Other pain conditions are associated with FM, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (Lupus), ankylosing spondylitis, interstitial cystitis, and more.[6]

In 2017, the United Kingdom's National Health Service listed fibromyalgia as one of 20 most painful conditions.[7][8] Fibromyalgia pain may be described as diffuse aching or burning, head to toe, and can be worse at some times than at others. The pain can change location and fluctuate in intensity.[7][9][2] The United States (US) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) states fibromyalgia is a serious disorder, and "can cause pain, disability, and lower quality of life."[2]

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) created and updates the diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia.[1][10][11][1][4] See: Fibromyalgia (Diagnosis).

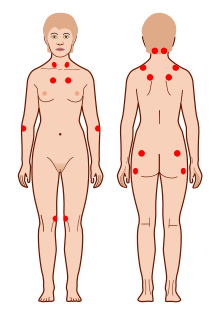

Image: Wikimedia Commons by author Jmarchn. License: CC-by-sa-3.0

Prevalence

An estimated 4 million people in the US[2] and 2-5% of the world population have fibromyalgia (Clauw et al, 2011). Fibromyalgia is the second most common rheumatic disorder behind osteoarthritis[3] and is considered by many pain experts to be a central nervous system disorder which is most often lifelong[12] that is not fatal.[13] It is occurs in women, men, children, and all ethnic groups. Fibromyalgia is often seen in families and most commonly diagnosed in middle aged people, and prevalence increases with age.[14][3]

FM is a female predominant disease, diagnosed with female:male of between 7:1 and 1.5:1, depending on the criteria used.[10][11][1][4][15] See: Fibromyalgia (American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Criteria). A September 2018 study by Wolfe et al. found fewer women and more men are diagnosed under the 2010/11 criteria[16] (this criterion further updated in 2016[17]).

What we did not find in our unbiased CritFM samples was 9:1 female to male fibromyalgia ratios that are widely described by expert sources [11–13]. We believe that such findings only occur in the presence of selection bias or biased ascertainment.[16]

As unbiased epidemiological studies show only a small increase in the female to male sex ratio (~1.5:1) as opposed to the observed ratio in clinical studies of 9:1, we believe that the over-identification of fibromyalgia in women and the consequent under-identification of men is the result of bias.[16]

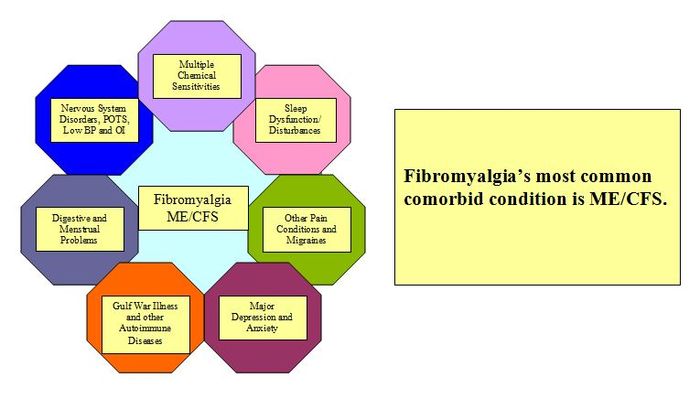

Fibromyalgia in ME/CFS

The most common overlapping condition with ME/CFS is fibromyalgia.[18][19] While some have posited ME/CFS and FM are variants of the same illness, Benjamin Natelson, MD summoned considerable amounts of data that suggest the two illnesses differ with different pathophysiologic processes leading to different treatments.[20]

Dr. Jarred Younger has said that many patients that meet the criteria for FM also meet criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) but the reverse is not necessarily true as a lot of people with CFS do not have widespread pain.[21] However, the Canadian Consensus Criteria (CCC) requires the symptom of pain to diagnose ME/CFS.[22] It is the pattern (on both sides of the body, and above and below the waist) of chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain (involving muscle, cartilage, ligaments, and connective tissue) in FM that sets it apart from other diseases that have pain; it also causes cognitive symptoms and unrefreshing sleep.[5][6]

A Swedish study of 234 ME/CFS patients meeting the Canadian Consensus Criteria found that 96% had trigger point pain consistent with fibromyalgia and 67% met the diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia.[23]

Health complications

Fibromyalgia is not considered a progressive disease[24] but according to Dr. Dan Clauw the "slow gradual worsening of chronic pain patients over time is due to downstream consequences of poorly controlled pain and other symptoms, wherein individuals then progressively get less active, sleep worse, are under more stress and unknowingly develop bad habits which worsen pain and other symptoms."[25]

The CDC recognizes the following complications:

- Lower quality of life

- Especially for women with fibromyalgia

- More hospitalizations

- In the United States people with fibromyalgia are twice as likely to be hospitalized

- Higher rates of major depression

- Adults with fibromyalgia are more than 3 times more likely to have major depression than adults without fibromyalgia, and rates of depression and other mood disorder symptoms are higher than in most other illnesses.[14][26]

- Death rates from suicide and injuries are higher in people with FM

- Overall life span remains similar to the general population.

- Higher rates of other rheumatic conditions

- Comorbidities include other types of arthritis such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and ankylosing spondylitis.[14]

The American College of Rheumatology states that:

- Other conditions often occur in fibromyalgia patients

- Depression or anxiety

- Migraine or tension headachess

- Digestive problems, e.g. irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Irritable or overactive bladder

- Pelvic pain

- Temporomandibular joint disorder (TMD)[27]

Risk factors

Fibromyalgia is more likely to occur in middle-aged people but can affect any age group, including children. It is more common in women and girls, in obese people and in people with a family history.[28]

Rheumatic illnesses are risk factors in developing FM, especially lupus and rheumatoid arthritis (RA).[14]

Events linked to causing fibromyalgia to develop include car accidents, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), repetitive injuries, and illnessss such as a virus.[2][28]

Diagnosis

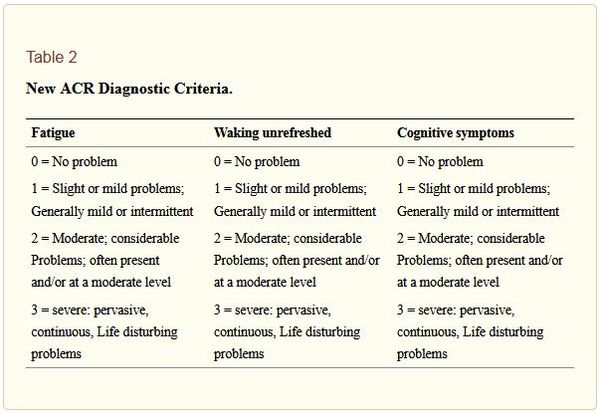

The American College of Rheumatology publishes the most widely used diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia.[1][2] Tender points, not trigger points, are used to diagnose fibromyalgia.[29]

In fibromyalgia, painful areas of the body will be both above and below the waist, and on both sides of the body. (See: 1990 ACR and 2010 ACR images above right depicting tender points.) It is important for clinicians to check for other conditions that could be causing pain such as hypothyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, osteoarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and polymyalgia rheumatica.[30]

United States

2010 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Criteria

The new ACR criteria for fibromyalgia assesses:

- Widespread Pain Index (WPI), which replaces the older tender points assessment, and

- Symptom Severity Score (SS), which assesses somatic symptoms other than pain[1]

Widespread pain index

There are 19 areas in the widespread pain index (WPI) in the newer ACR criteria.[31][1]

Image source: Wikimedia Commons by author Jmarchn. License: CC-by-sa-3.0.

This Widespread Pain Index (WPI) is scored out of 19, and is one of the two required scores needed for a doctor to make a diagnosis of fibromyalgia, and is considered in combination with the SS score.[24][1]

Symptom severity

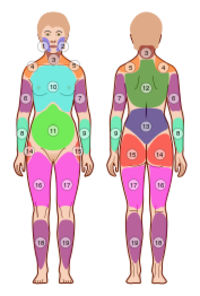

The Symptom Severity score ranks each of the following groups of fibromyalgia symptoms on a scale of 0-3, giving a SS score out of 12:

- Fatigue

- Waking unrefreshed

- Cognitive symptoms

- Somatic (physical) symptoms in general (such as headache, weakness, bowel problems, nausea, dizziness, numbness/tingling, hair loss, dry eyes, Raynaud's phenomenon, painful urination, and more.[24][1]

Source: Jahan F, Nanji K, Qidwai W, Qasim R. Fibromyalgia Syndrome: An Overview of Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management. Oman Med J 2012 May; 27(3):192-195. doi: 10.5001/omj.2012.44 license: CC-BY-NC

A fibromyalgia diagnosis is based on both the WPI score and the SS score either:

- WPI of at least 7 and SS scale score of at least 5, or

- WPI of at least 4 and SS scale score of at least 9

- with symptoms present for at least three months[24][32]

The 2010 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) proposed diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia[1][4] was modified in 2011,[17] with the modification being validated in 2013 and published in 2014.[33] In September 2016, another revision was been made.[32]

Take the online Fibromyalgia test

This online test by fibromyalgiaforums.org uses the ACR 2010 Criterion to help diagnose fibromyalgia.

Tender point test phased out

The older 1990 criteria's tender point examination was replaced because men often do not seem to form the tender points needed for diagnosis.[34] The 2010 proposed criteria correctly diagnosed more men, with a female:male ratio of 2:1.[15]

Tender point examination was also problematic because "considerable skill is needed to correctly check for a patient's tender points (i.e., digital palpation that is done with certain amount of applied pressure)", but this technique was not taught at most medical schools.[35][31]

- The new standards were designed to:

- eliminate the use of a tender point examination

- include a severity scale by which to identify and measure characteristic FM symptoms

- utilize an index by which to rate pain[31]

1990 ACR criteria

Image source: WikiMedia Commons, authors Sav vas and Jmarchn, license: CC0 / public domain.

- 1990, The American College Of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria For The Classification Of Fibromyalgia[10][11] "American College of Rheumatology guidelines suggest that people with fibromyalgia have pain in at least 11 of these tender points when a doctor applies a certain amount of pressure."[35][31]

US Social Security Administration

The United States Social Security Administration (SSA) accepts a diagnosis of FM with either the 2010 or 1990 ACR criteria.[10][11][1][4][36]

Sleep studies

Sleep dysfunction is often involved in FM. Treating a sleep disorder or sleep problems may help with FM symptoms, for example fatigue. Sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome and nocturnal myclonus are often found in fibromyalgia patients, and waking unrefreshed is a diagnostic symptom of fibromyalgia.[35][1] A diagnosed sleep disorder is also helpful if one needs to file for disability.

Brain scans

Brain scans are a potential aid to help diagnose fibromyalgia.[37][38] A small study by López-Solà et al. (2017) using a combination of fMRI brain scans and artificial intelligence (machine learning) correctly diagnosed 95% of fibromyalgia patients.[39]

A number of brain imaging studies have found significant results in patients with fibromyalgia, including a fMRI study that found patients with FM "have measurable pain signals in their brains, from a gentle finger squeeze that barely feels unpleasant to people without the disease"[40] and MR/PET imaging by Loggia et al 2015 found neuroinflammation due to glial activation.[41]

Blood tests and biomarkers

EpicGenetics developed the FM/a test blood test to diagnose FM in 2017 - and announced a linked treatment trial involving the BCG vaccine soon after; the trial has since been suspended indefinitely.[42][43][44] Dr Denise Faustman at Massachusetts General Hospital, who was due to conduct the trial, stated that the test should never have been marketed as a requirement for the treatment trial, and that no patients were ever recruited to the trial.[44]

The FM/a test continues to be marketed despite the suspension of the linked treatment trial,[44] and the fact that only two studies have been published using the test - the last being published in 2015.[45][46] The evidence base supporting the use of the test has been reported to be weak, and no studies have assessed whether the test can correctly determine which patients have fibromyalgia and have some fibromyalgia symptoms that are explained by another diagnosis.[42] One study did not include any men.[45]

IsolateFibromyalgia, IQuity's RNA based blood test for fibromyalgia, was first announced in 2018 but no peer-reviewed studies have been published.

A non-invasive eye test has found eye abnormalities in people with fibromyalgia, with Garcia et al 2016 finding reduced retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness, raising hopes of a non-invasive eye test may help diagnose FM.[47] The findings were confirmed by Cordón et al 2021, who found that disease severity and reduced quality of life were associated with reduced RNFL.[48] The test requires optical coherence tomography (OCT), which is fast and non-invasive.[48] At present, there is no eye test in clinical use for diagnosing FM.

In 2019, Hackshaw and colleagues found a unique metabolic fingerprint using a blood spot test that distinguished between fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, which they suggested could act as a diagnostic biomarker for FM.[49]

Heart rate variability (HRV) measured by ECG is a possible fibromyalgia biomarker, since it is reduced in people with FM, but heart rate is affected by many different factors so this may be problematic.[37]

ICD Diagnostic code

ICD-10

The World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Diseases (ICD) lists FM as a "disease of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue", under the code M79.7 (WHO ICD-10 Version: 2016).[50] The WHO's ICD-10 does not refer to FM as a syndrome and it is not classified in the category for medically unexplained symptoms.[51][50]

- M79.7 Fibromyalgia

- Fibromyositis

- Fibrositis

- Myofibrositis[50]

In 2015, the US finally adopted ICD-10 and FM as a diagnosis.[51][52]

ICD-11 (2019)

The ICD-11 (2019) has diagnostic code MG30.1 Chronic widespread pain, and changed the category from a Musculoskeletal disease, to the General signs and symptoms category, sometimes referred to as Medically unexplained physical symptoms.[53]

- MG30.01 Chronic widespread pain

Parent

- MG30.0 Chronic primary pain

Description

Chronic widespread pain (CWP) is diffuse pain in at least 4 of 5 body regions and is associated with significant emotional distress (anxiety, anger/frustration or depressed mood) or functional disability (interference in daily life activities and reduced participation in social roles). CWP is multifactorial: biological, psychological and social factors contribute to the pain syndrome. The diagnosis is appropriate when the pain is not directly attributable to a nociceptive process in these regions and there are features consistent with nociplastic pain and identified psychological and social contributors.[53]

Inclusions

- Fibromyalgia

Exclusions

- Acute pain (MG31)[53]

Differential diagnosis

Conditions which have symptoms that are similar to fibromyalgia, particularly involving chronic widespread pain and fatigue should be ruled out, either by the routine tests recommended to aid fibromyalgia diagnosis, or by symptom pattern and history.

Differential diagnoses for fibromyalgia include:

- Inflammatory rheumatic diseases:

- Rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren's syndrome, mixed connective tissue disease, scleroderma, or inflammatory spondyloarthritis, inflammatory polyarthritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, inflammatory myopathy or systemic inflammatory arthropathies

- Musculoskeletal or spinal conditions:

- Myofascial pain syndrome, hypermobility syndromes including Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, spinal stenosis, myelopathies, myositis

- Endocrine and metabolic disorders:

- Hashimoto's thyroiditis (hypothyroidism), hyperparathyroidism, acromegaly, and vitamin D deficiency

- Gastrointestinal diseases:

- Celiac disease or other forms of irritable bowel disease, Non-celiac gluten sensitivity

- Infectious diseases::

- Lyme disease, hepatitis C, and HIV, although these are not routinely tested for, Chronic Lyme disease may be secondary to fibromyalgia

- Cancers at the very early stages:

- fever, night sweats, and weight loss are common signs

- Neurological conditions:

- Multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease and peripheral neuropathies

- Medication-induced pain conditions:

- statins, opioids (opioid-induced hyperalgesia), some chemotherapy drugs, aromatase inhibitors, and bisphosphonates can cause diffuse pain [54][55]

The limited laboratory findings along with history and physical examination can help differentiate fibromyalgia from other differentials.[55]

Pathophysiology

Fibromyalgia is a pain processing disorder involving altered pain processing in the central nervous system which causes widespread pain and a constellation of additional symptoms.[3]

Neuroimaging and brain imaging studies have shown that the pain and other symptoms of fibromyalgia appear to be caused by neurochemical imbalances in the central nervous system that lead to a central amplification of pain perception (Clauw et al., 2011).[3]

According to the CDC, there is no evidence that a single event "causes" fibromyalgia, instead it appears to be associated with many physical and/or emotional stressors and other risk factors that may trigger or aggravate symptoms. These include certain infections, such as a viruses or Lyme disease, as well as emotional or physical trauma (injury)."[2][14] The widespread pain is severe, debilitating, and abnormal in processing its pain. sleep disturbance and fatigue are common symptoms.[56]

- May 2012, Fibromyalgia Syndrome: An Overview of Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management[24] See Table 1: "Conditions associated with fibromyalgia." Musculoskeletal, genitourinary, gastrointestinal, and miscellaneous conditions often exist among fibromyalgia patients.

Pathophysiology: Although the etiology remains unclear, characteristic alterations in the pattern of sleep and changes in neuroendocrine transmitters such as serotonin, substance P, growth hormone and cortisol suggest that regulation of the autonomic and neuroendocrine system appears to be the basis of the syndrome. Fibromyalgia is not a life-threatening, deforming, or [progressive disease. Anxiety and depression are the most common association. Aberrant pain processing, which can result in chronic pain, may be the result of several interplaying mechanisms. Central sensitization, blunting of inhibitory pain pathways and alterations in neurotransmitters lead to aberrant neurochemical processing of sensory signals in the CNS, thus lowering the threshold of pain and amplification of normal sensory signals causing constant pain." (Firdous et al, 2012)[24]

The frequent co-morbidity of fibromyalgia with mood disorders suggests a major role for the stress response and for neuroendocrine abnormalities. The hypothalamic pituitary axis (HPA axis) is a critical component of the stress-adaptation response. In FMS, stress adaptation response is disturbed leading to stress induce symptoms. Psychiatric co-morbidity has been associated with FMS and needs to be identified during the consultation process, as this requires special consideration during treatment.[24]

- Jun 2018, SNPs in inflammatory genes CCL11, CCL4 and MEFV in a fibromyalgia family study.[57]

SNPs with significant TDTs were found in 36% of the cohort for CCL11 and 12% for MEFV, along with a protein variant in CCL4 (41%) that affects CCR5 down-regulation, supporting an immune involvement for FM.

- Jul 2018, Primary and Secondary Fibromyalgia Are The Same: The Universality of Polysymptomatic Distress

Fibromyalgia can be considered either primary, or dominant, also known as idiopathic fibromyalgia, or secondary. In the primary form, the causes of the disorder are unknown, but in secondary fibromyalgia, the disorder usually occurs alongside other debilitating medical conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), lupus, and multiple sclerosis.[58]

Immune system research

Dr. Jarred Younger believes an overactive immune system is the cause and will be conducting a study to test this hypothesis.[59][60] An overactive immune system can cause inflammation and chronic pain.[61][62]

Dr. William Pridgen's research of HSV-1 (cold sore virus) as being involved in FM has conducted a successful Phase III clinical trial, which had been fast-tracked by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), of a combination drug that suppresses this virus and also helps with pain.

Recognizing FM may involve activation of the immune system researchers performed exome sequencing on chemokine genes in a region of chromosome 17 identified in a genome-wide family association study. Their conclusion: "SNPs with significant TDTs were found in 36% of the cohort for CCL11 and 12% for MEFV, along with a protein variant in CCL4 (41%) that affects CCR5 down-regulation, supporting an immune involvement for FM."[57]

Dr David Andersson from the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience at King's College London, led a new study into Fibromyalgia being an immune system disorder.[63]

Andersson and his colleagues harvested blood from 44 people with fibromyalgia and injected purified antibodies from each of them into different mice. The mice rapidly became more sensitive to pressure and cold, and displayed reduced grip strength in their paws. Animals injected with antibodies from healthy people were unaffected.[64]

Prof Camilla Svensson from the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, who was also involved in the study, said: “Antibodies from people with fibromyalgia living in two different countries, the UK and Sweden, gave similar results, which adds enormous strength to our findings.”[64]

Brain and spinal cord research

A 2004 study by Heffez et al. studied 270 patients with FM and found that 46% had cervical spinal stenosis and 20% chiari malformation.[65] In 2007, Heffez et al. saw significant improvement in physical and mental well-being was found in patients with cervical stenosis who received surgery.[66] A second study in 2007 by Andrew Holman found that 71% had cervical spinal cord compression.[67] In the past many patients were misdiagnosed with FM when further testing would have revealed the correct diagnosis for the cause of their pain; the 2010 (updated in 2016) ACR criteria has helped curb misdiagnoses.[68][16]

Various types of brain imaging are being used to research FM.

In 2002, an fMRI study conducted by Richard Gracely and Daniel Claw found people with FM "have measurable pain signals in their brains, from a gentle finger squeeze that barely feels unpleasant to people without the disease."[69] A 2007 study by Borsook et al. found decreased gray matter density relative to controls in cingulate cortex (CC), medial prefrontal cortex (Med. PFC), parahippocampal gyrus (PHG) and insula.[70] In 2015, Loggia et al. imaged neuroinflammation due to glial activation using MR/PET imaging.[41] In 2017, López-Solà et al. identified three brain patterns based on fMRI responses to pressure pain and non-painful multisensory stimulation. "These patterns, taken together, discriminate FM from matched healthy controls with 92% sensitivity and 94% specificity."[39] In 2018, Albrecht et al used PET scans to document glial activation.[71] Also in 2018, Martucci et al. found unbalanced activity between the ventral and dorsal cervical spinal cord. Ventral neural processes were increased and dorsal neural processes were decreased which may reflect the presence of central sensitization contributing to fatigue and other bodily symptoms in FM.[72]

Fibromyalgia is not the same as depression

- Oct 24, 2003, Fibromyalgia Isn't Depression[73]

Depression doesn't cause the pain of fibromyalgia, a new study shows.[73]

"People still doubt fibromyalgia is a disease," Giesecke tells WebMD. "Previously, we found that fibromyalgia patients really do have increased central pain processing. Now we can show this is not affected by depression. Something is wrong here, and it is not at all connected with depression."[73]

"Giesecke's group looked at brain responses to painful stimuli, and then checked to see if there was any difference between depressed and nondepressed fibromyalgia patients. They showed the activation of areas of the brain related to pain were not different in patients with and without depression." But there is a difference between people with and without fibromyalgia, he says.[73]

The researchers use an imaging device called functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI, to look at how the brain responds to pain. Study participants get a mildly painful pressure on their thumb, which makes the brain's pain centers "light up" on the image. Thumb pressure -- at a level healthy people hardly feel -- sets off a firestorm in the pain centers of fibromyalgia patients' brains.[73]

- 2013, Small fibre pathology in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome[74]

- A study involving skin biopsies funds that fibromyalgia is neuropathic - and not a form of depression or a Psychosomatic Disorder

The study authors stated, "This strengthens the notion that fibromyalgia syndrome is not a variant of depression, but rather represents an independent entity that may be associated with depressive symptoms". The findings also point "towards a neuropathic nature of pain in fibromyalgia syndrome... with regard to the persistent somatoform pain disorder that is sometimes assumed to be underlying in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome, our study shows a clear distinction to fibromyalgia syndrome: persistent somatoform pain disorder (ICD-10 F45.40) may be present in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome, however, in the majority of cases the definition of pain starting in connection with an emotional conflict situation or psycho-social stress strong enough to be taken as a crucial aetiological influence and pain in the course of a primary depressive disorder or schizophrenia in addition to chronic widespread pain lasting longer than 6 months is not fulfilled."[74]

Insulin resistance

In 2019 a small observation study by Pappolla et al. was published that found insulin resistance was associated with fibromyalgia, however the study was quickly retracted due to both criticisms of the methodology and issues with ethics approval requirements. Some of the same authors, including Pappolla, published a second observational study in 2021, again showing a likely association between having insulin resistance and fibromyalgia.[75]

Comorbidities, overlapping conditions, and common symptoms

Overlapping conditions

The most common overlapping medical conditions in people with fibromyalgia are ME/CFS, IBS, Temporomandibular joint disorder (TMD), interstitial cystitis, multiple chemical sensitivity, chronic tension-type headache, and chronic low back pain[78]

Allodynia

Allodynia is when ordinary sensations cause pain, and is common in people with fibromyalgia.[79][80]

The main types of allodynia are:

- Mechanical / Tactile

Caused by movement across the skin such as a cotton bud, or brushing a painter's brush against the skin; or by light pressure or touch, e.g. clothing or bedsheets touching the skin.

- Thermal / Temperature

Caused by heat or cold that is not extreme enough to cause damage to skin tissues.[81]

Anxiety

Anxiety is more common in people with fibromyalgia than in healthy people.[27][82]

Body temperature

Hypersensitivity to cold or heat is common in fibromyalgia, especially in people with allodynia.[80]

Small fiber peripheral neuropathy occurs in some people with fibromyalgia, causing a combination of temperature sensitivity, burning, tingling, and prickling due to paresthesia, numbness, dry eyes and dry mouth.[1][83]

Chest pain

Chest pain has been reported in many people with fibromyalgia. A study of over 2,000 FM patients prescribed the popular pain drugs Lyrica or Cymbalta found that approximately 23% had chest pain.[84]

Cognitive dysfunction and Fibro fog

The cognitive problems or "fibro fog" in fibromyalgia are part of the diagnostic criteria, although brain fog in general occurs in a number of different health conditions.[1] Cognitive dysfunction in fibromyalgia includes problems with thinking and memory.[85] Fibromyalgia is known to cause multiple types of cognitive impairment.[86]

Fibro fog

The "Fibro fog" or brain fog in fibromyalgia is a highly disabling symptom that includes memory problems, problems managing activities/schedule, difficulty with verbal expression, focus/concentration, and generally experiencing "life in a haze".[87] Fibro fog has been found to linked to the degree of pain and was found to be unrelated to any depression or anxiety that some people with fibromyalgia also have.[85]

The term dyscognition is sometimes used to refer to signs of cognitive problems, including diminished performance on tests of memory tests, verbal fluency, attention and concentration problems, reduced executive functioning.The Multiple Ability Self-Report Questionnaire (MASQ) is often used to assess cognitive dysfunction in fibromyalgia research, including "fibro fog".[87]

Improving pain and sleep may reduce cognitive impairment. Treatment for cognitive dysfunction in FM including "fibro fog" include transcranial direct current stimulation, physical activity, and CBT for sleep although studies are limited.[88] One randomized controlled trial found CBT for sleep difficulties in FM improved executive functions and alertness but sleep hygiene did not.[88]

Depression and anxiety

Fibromyalgia sufferers are "up to three times more likely to have depression at the time of their diagnosis than someone without fibromyalgia."[89] Anxiety is also more common.[27]

Differences between depression and fibromyalgia

- Depression and anxiety are common in fibromyalgia but are not core diagnostic symptoms, so they are not required for a diagnosis of fibromyalgia in the ACR criteria[10][1]

- A study of over 3,000 patients by Koroschetz et al. (2011) found that a significant number of people with fibromyalgia have never had depression.[90]

- Fibromyalgia is a diagnosis of chronic widespread pain, but pain is part of the diagnostic criteria for depression.[91][73]

- Jensen et al. (2010) found that anxiety and depression are not linked to increased pain sensitivity or alertered pain processing, which are key mechanisms in fibromyalgia.[82]

Dry eye syndrome

Sjögren's syndrome, also known as Sicca or dry eye syndrome causes dry eyes and a dry mouth; it is a less common comorbidity in people with fibromyalgia.[24][92]

Fatigue

Most people with fibromyalgia experience fatigue, and it is a recognized diagnostic symptom. Some people with fibromyalgia also met the full diagnostic criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome.[27][1]

Fibro fog

See cognitive dysfunction and Fibro fog.

Gastrointestinal problems

IBS often occurs in people with fibromyalgia.[3]

Gulf War Illness

GWI increases risk of developing fibromyalgia.[93]

Hyperalgesia

Fibromyalgia involves an increased sensitivity to painful stimuli, known as hyperalgesia. Hyperalgesia has been described as a lowered pain threshold, and can be thought of as "increasing the volume" of pain.[3]

Interstitial cystitis

Interstitial cystitis is a common comorbidity in people with fibromyalgia, and causes a painful bladder.[3][94]

Irritable bowel syndrome

IBS is a particularly common comorbidity in people with fibromyalgia. Other digestive system problems may also occur.[3]

Language impairment and word-finding problems

The "fibro fog" or brain fog that is a well recognized symptom of FM typically causes problems with words and language.[1] Cognitive impairment in fibromyalgia includes:

- Word-finding problems[85][20]

- short-term memory problems

- vulnerability to distraction by irrelevant stimuli (known as "selective attention")

- mental slowing

- information overload, and

- multi-tasking problems

- attention and concentration problems[88][87][95]

Lower back pain

Mechanical lower back pain is more common in patients with FM.[55] A study of over 2,000 FM patients prescribed the popular pain drugs Lyrica or Cymbalta found that over 60% had some form of lower back pain.[84]

Mast Cell Activation Syndrome

Migratory bone pain, joint pain or muscle pain and fibromyalgia are common in people with mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS). MCAS is far less common than fibromyalgia and it is unclear how many fibromyalgia patients also have MCAS.[96][97] The MCAS consensus criteria (2020) states that it is unclear how many people with fibromyalgia may have MCAS associated with their fibromyalgia, or as a cause of their fibromyalgia.[96]

Menstrual cycle effects

Schertzinger et al. (2017) found that levels of the sex hormones progesterone and testosterone were linked to pain severity in fibromyalgia.[98]

Migraine and headaches

Both tension-type headaches and migraines are commonly in patients with fibromyalgia.[3][27]

Both fibromyalgia and migraine may reflect problems in the brain’s pain processing center. It is believed that both conditions are caused by excitation of the nervous system or an over-response to stimuli. Stress is usually cited as a trigger for both migraine and fibromyalgia attacks.[99]

Mood disorder symptoms

While depression and depressive symptoms are common in FB, bipolar disorder symptoms are also much more common than in the general population. Alciati et al 2012 reports on this.[26]

Multiple Chemical Sensitivity

Multiple chemical sensitivity (MCS) has been found in approximately 50% of fibromyalgia patients, although this is based on a very small number of studies using the 1990 ACR criteria for fibromyalgia.[100][101][102] MCS has been referred to as a partially overlapping condition, with fatigue and headaches occurring in both FM and MCS, and muscle or joint pain being reported in some people with MCS.[78][103]

Obesity

Obesity is commonly found in patients with fibromyalgia, and increased body mass index been linked to increased pain severity and increases in other fibromyalgia symptoms, however the effects of weight loss on fibromyalgia symptoms is not clear.[104][84] A few studies have reported positive effects from weight loss in FM, either by bariatric surgery, a combination of diet and exercise combination or behavioral weight loss.[104]

Obstetrics and gynaecology

Chronic pelvic pain and vulvodynia, which is chronic pain around the opening of the vagina, are particularly common in women with FM.[3][55][105]

Early menopause and hysterectomy are linked to increased risk of fibromyalgia.[106] A number of studies have found that women with fibromyalgia were more likely to have had a hysterectomy than the general population, and they were more likely to have poorer health and higher health costs than women with fibromyalgia who had not had a hysterectomy.[107] Fibromyalgia patients were more likely to have had a gynaecological surgery compared to other chronic pain patients, with rates of fibromyalgia being higher in patients who had hysterectomy, oophorectomy (ovary removal) and cystectomy (bladder or cyst removal) than only hysterectomy.[108]

Pregnancy complications have been found to be more common in women with fibromyalgia,[109] and the menstrual cycle has been found to be related to pain fluctuations in fibromyalgia.[98]

Orthostatic intolerance (OI)

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and other forms of orthostatic intolerance often occur in people with fibromyalgia.[76] Symptoms can include low blood pressure on standing and/or sudden high blood pressure, dizziness, fainting.

Dr Charles Lapp found that fibromyalgia symptoms and ME/CFS symptoms predicted the outcome of tilt table testing for orthostatic intolerance.[110] Orthostatic intolerance may often be l overlooked in fibromyalgia patients.[111]

Painful bladder syndrome and chronic pelvic pain

Painful bladder syndrome and chronic pelvic pain are common comorbidities in people with fibromyalgia.[3]

Pregnancy complications

A study of 12 million live births found that fibromyalgia was a "high risk" condition in pregnancy, associated with higher rates of gestational diabetes, venous thromboembolism, delivery by cesarean, and intrauterine growth restriction in the babies.[109]

Prostate symptoms

Men with fibromyalgia commonly experience inflammation of the prostate, known as chronic prostatitis, and prostadynia, which is a chronic nonbacterial and painful inflammation of the prostate. These cause chronic pelvic pain.[3][112] Frequent and urgent urination are common.[112]

Raynaud's syndrome

In Raynaud's syndrome or Raynaud's phenomenon, the blood vessels narrow more than they should, which means less blood to get through, making your extremities cold, and making them extremely difficult to warm up. Reynauld's causes fingers, toes, lips, nose, and other parts of you go cold and numb. Fingers and toes change color to white, then blue. As you warm up, skin turns red and they feel tingle, throb or swell up. Reynauld's attacks are caused by cold or emotional stress.[113]

Raynaud's symptoms have been commonly reported in people with fibromyalgia.[24][1][114]

Rheumatic conditions - other rheumatic conditions

Osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and ankylosing spondylitis are more common in people with fibromyalgia.[14]

Sleep dysfunction

Sleep problems occur in most people with FM.[27] Waking unrefreshed is a diagnostic symptom, and the sleep disorders sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome and nocturnal myclonus are common in people with fibromyalgia.[1][35]

Vatthauer et al. (2015) found that sleep was associated with task-negative brain activity in fibromyalgia participants with comorbid chronic insomnia.[115]

The present results of this study suggest that long-term, comorbid pain and sleep disturbance may be associated with increased activation in core default mode brain areas that is above and beyond long-term pain disturbance alone.[115]

Stress and Post-traumatic stress disorder

PTSD, which is a mental illness that results from traumatic events, is a risk factor for fibromyalgia.[27][28]

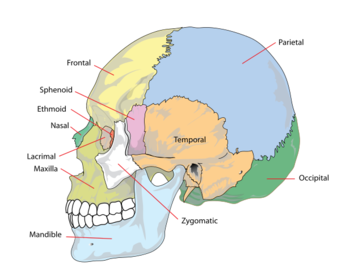

Temporomandibular disorder or temporomandibular joint disorder (TMD/TMJ)

Source: LadyofHats on Wikimedia Commons, public domain image.

TMD, previously known as TMJ, is common in people with fibromyalgia.[3] TMD symptoms other than headaches include:

- Jaw pain

- Discomfort or difficulty chewing

- Painful clicking in the jaw

- Difficulty opening or closing the mouth

- Locking jaw

- Ringing in the ears[116]

A review by Soares et al (2015) found fibromyalgia has "characteristics that constitute predisposing and triggering factors for TMD".[117]

Thyroid disease

People with Hashimoto's autoimmune thyroid disease often experience significant fatigue and body aches. While these symptoms are common in Hashimoto's, they can also be markers of other diseases, like chronic fatigue syndrome or fibromyalgia.[54][118]

Other symptoms

- Fibromyalgia Syndrome: An Overview of Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management Conditions associated with fibromyalgia. (Table 1)

- Fibromyalgia - StatPearls

Treatment

Main treatment approaches for fibromyalgia include patient education, exercise including stretching, message, medication, alternative treatments for pain management, and stress management or mental health treatments for any related depression or anxiety.[citation needed][2][3]

United States

Rheumatology and primary care providers: Diagnosing and treatment:

- 2012, A Framework for Fibromyalgia Management for Primary Care Providers[119] Rheumatologists stopped treating fibromyalgia patients and primary care providers began treatment managment although rheumatologists are most often the specialist to diagnose.

Drugs

Therapies

Exercise

Please Note: The research supporting these treatments are for fibromyalgia patients without ME/CFS sufferers due to it's hallmark symptom of post-exertional malaise.

Several studies have found that warm-water pool exercise is a beneficial treatment for fibromyalgia. A very large survey of patients found that 26% have used pool therapy, rating it as very effective.[122] The same survey found 74% of patients found heat helpful - either warm water or heat packs.[122] Warm water especially important in FMS because the vasodilatory effect of the heating may improve blood flow to muscles, helping to reduce pain, and many people with FM are also intolerant of cold. A warm-water pool is one that's kept around 89.6 to 93 degrees Fahrenheit (32 to 34 Celsius), which is several degrees warmer than most heated pools.[123]

Dr Roubenoff Ronenn recommends moderate aerobic exercise and weights with six to eight reps, and then a day or two of rest in between. He cautions people not to start a program if they are in a flare.[120]

Massage

- 2014, Massage Therapy for Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials[124]

Acupuncture

Manual acupuncture (skin penetration without stimulation) is the most common form of acupuncture but gives no clinically significant pain relief to fibromyalgia patients, but a Cochrane review found electro-acupuncture, which involves an electrical current, significantly reduced pain, stiffness, and fatigue and improve sleep quality and global well-being in people with fibromyalgia for a one-month period, but not long term.[35][125]

2016 reviewed acupuncture (AC), electroacupuncture (EAC) and moxibustion, but found none improved quality of life in women with fibromyalgia.[126] "There was no significant improvement in pain or reduction of tender points in any of the groups studied, at the end of the 8th session."[126]

In 2004, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) ruled a noncoverage determination for acupuncture.[127]

Controversies

Dr. Frederick Wolfe

Dr. Frederick Wolfe, the director of the National Databank for Rheumatic Diseases and the lead author of the 1990 paper that first defined the diagnostic guidelines for fibromyalgia, says he has become cynical and discouraged about the diagnosis. He now considers the condition a physical response to stress, depression, and economic and social anxiety.[128][129]

Fibromyalgia and Chiari malformation

Some individuals diagnosed with FMS were undergoing surgery for chiari malformation (CM). These are two separate conditions; FMS cannot be resolved by undergoing a risky CM surgery.[130][131]

- Most patients with FM do not have CIM pathology. Future studies should focus on dynamic neuroimaging of craniocervical neuroanatomy in patients with FM.[130]

Blood test

EpicGenetics developed a blood test to identifying the presence of specific white blood cell abnormalities of patients diagnosed with FM - FM/a® test - and announces a linked treatment trial although the trial never started and is now suspended.[44] EpicGenetics offers help to determine if your insurance will cover their test.[43]

The FM/a test continues to be marketed despite the suspension of the linked treatment trial,[44] and the fact that only two studies have been published using the test - one comparing fibromyalgia patients with healthy controls, and another with lupus and rheumatoid arthritis patients.[45][46] In the 6 years since the last study was published, no further research has appeared on the FM/a test, leaving many to conclude that the evidence base is weak.[42]

IsolateFibromyalgia, IQuity's RNA based blood test for fibromyalgia, was first announced in 2018 but has insufficient data supporting its use: no peer-reviewed studies had been published by 2021.

Disability: SSI/SSD and LT

Famous people

Celebrities and famous people with fibromyalgia include:

- Frida Kahlo, famous Mexican painter

- Florence Nightingale, founder of modern nursing

- Lady Gaga (Stefani Germanotta), American singer/artist

- Morgan Freeman, American actor

- Jo Guest, British model

- Janeane Garofalo, actor and comedienne[132][133]

Notable studies

News articles and features

- 2021, In a sea of skeptics, this physician was one of fibromyalgia patients' few true allies. Or was he? - STAT news reports on the marketing of the FM/a test, and the linked treatment that never started.

- 2021, Fibromyalgia may be a condition of the immune system not the brain – study - The Guardian

- 2017, fMRI Can Help Diagnose Fibromyalgia - The Rheumatologist, 2017

See also

- Fibromyalgia disability process

- Fibromyalgia drugs

- Fibromyalgia notable studies

- Influenza vaccine

- List of famous people with ME, CFS, and/or FMS

- Lady Gaga

- Mayo Clinic Guide to Fibromyalgia: Strategies to Take Back Your Life - book (2019)

Learn more

- Fibromyalgia - CDC

- The Science of Fibromyalgia - Daniel Clauw, Lesley Arnold, and Bill McCarber for the FibroCollaborative

- 8 Things to Know About Fibromyalgia - AARP

- Fibromyalgia isn't depression - WebMD

- 2012, | title = 20 Painful Health Conditions 20 Painful Health Conditions - NHS (archived copy)

- 2017, Diagnostic confounders of chronic widespread pain: not always fibromyalgia

- Forum: Fibromyalgia and Connective Tissue Disorders at Science for ME

- 2022, What’s the Difference Between Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Fibromyalgia? - Verywell Health

Diagnosing and categorizing fibromyalgia

- 2017, Study Reveals New Treatment Target for Fibromyalgia: Inflammation in the Brain

- 2017, AI can spot the pain from a disease some doctors still think is fake

- 2018, Fibromyalgia: Central Sensitization Syndrome - Characterizing classes of fibromyalgia within the continuum of central sensitization syndrome - ProHealth

Blood tests

- 2021, In a sea of skeptics, this physician was one of fibromyalgia patients' few true allies. Or was he? - STAT News on the FM/a test

- 2014, ICM-1: Fibromyalgia Antiviral Trial Results “Very Positive”: Predicts New Approach Will Be “Game-Changer”

Brain scans

- 2002, Functional magnetic resonance imaging evidence of augmented pain processing in fibromyalgia[40]

- 2012, Fibromyalgia and the brain: New clues reveal how pain and therapies are processed[citation needed]

- 2018, Brain glial activation in fibromyalgia – A multi-site positron emission tomography investigation[134]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 Wolfe, Frederick; Clauw, Daniel; Fitzcharles, Mary-Ann; Goldenberg, Don; Katz, Robert; Mease, Philip; Russel, Anthony; Russel, I. Jon; Winfield, John; Yunus, Muhammad (May 2010). "American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia" (PDF). Arthritis Care & Research (PDF). 62 (5): 600–610. doi:10.1002/acr.20140.

The reference list consisted of: muscle pain, irritable bowel syndrome, fatigue/tiredness, thinking or remembering problem, muscle weakness, headache, pain/cramps in the abdomen, numbness/tingling, dizziness, insomnia, depression, constipation, pain in the upper abdomen, nausea, nervousness, chest pain, blurred vision, fever, diarrhea, dry mouth, itching, wheezing, Raynaud’s phenomenon, hives/welts, ringing in ears, vomiting, heartburn, oral ulcers, loss of/change in taste, seizures, dry eyes, shortness of breath, loss of appetite, rash, sun sensitivity, hearing difficulties, easy bruising, hair loss, frequent urination, painful urination, and bladder spasms.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 "Fibromyalgia | Arthritis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. January 6, 2020. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 Clauw, Daniel J.; Arnold, Lesley M.; McCarberg, Bill H. (September 2011). "The Science of Fibromyalgia". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 86 (9): 907–911. doi:10.4065/mcp.2011.0206. ISSN 0025-6196. PMC 3258006. PMID 21878603.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 "2010 Fibromyalgia Diagnostic Criteria - Excerpt" (PDF). American College of Rheumatology. 2010.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 "Fibromyalgia Symptoms". WebMD. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 "Fibromyalgia - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "20 Painful Health Conditions". National Health Service. June 23, 2017. Archived from the original on May 30, 2018.

- ↑ Osborne, Hannah (October 29, 2018). "Here are 20 of the most painful health conditions you can get". Newsweek. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ↑ "What is Fibromyalgia". Fibromyalgia Action UK. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Wolfe, Frederick; Smythe, Hugh; Yunus, Muhammad; Bennett, Robert; Bombardier, Claire; Goldenberg, Don; Tugwell, Peter; Campbell, Stephen; Abeles, Micha (1990). P Clark; A Fam; S Farber; J Fiechtner; CM Franklin; R Gatter; D Hamaty; J Lessard; A Lichtbroun; A Masi; G McCain; WJ Reynolds; T Romano; IJ Russell; R Sheon. "The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia" (PDF). Arthritis and Rheumatism. The American College of Rheumatology. 33 (2): 160–172.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Wolfe, Frederick (1990). "1990 Fibromyalgia Excerpt" (PDF). American College of Rheumatology.

- ↑ Harte, Steven E.; Harris, Richard E.; Clauw, Daniel J. (2018). "The neurobiology of central sensitization". Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research. 23 (2): e12137. doi:10.1111/jabr.12137. ISSN 1751-9861.

- ↑ "Fibromyalgia". Office on Women's Health. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (January 6, 2020). "Fibromyalgia | Arthritis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Boomershine, Chad (November 4, 2017). "Fibromyalgia: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology". Medscape.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Wolfe, Frederick; Walitt, Brian; Perrot, Serge; Rasker, Johannes J.; Häuser, Winfried (September 13, 2018). "Fibromyalgia diagnosis and biased assessment: Sex, prevalence and bias". PLOS ONE. 13 (9): e0203755. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0203755. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 30212526.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "2016 Revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 46 (3): 319–329. December 1, 2016. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.08.012. ISSN 0049-0172.

- ↑ Carruthers, BM; van de Sande, MI; De Meirleir, KL; Klimas, NG; Broderick, G; Mitchell, T; Staines, D; Powles, ACP; Speight, N; Vallings, R; Bateman, L; Bell, DS; Carlo-Stella, N; Chia, J; Darragh, A; Gerken, A; Jo, D; Lewis, DP; Light, AR; Light, KC; Marshall-Gradisnik, S; McLaren-Howard, J; Mena, I; Miwa, K; Murovska, M; Stevens, SR (2012), Myalgic encephalomyelitis: Adult & Paediatric: International Consensus Primer for Medical Practitioners (PDF), ISBN 978-0-9739335-3-6

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Jason, Leonard; Taylor, R.R.; Kennedy, C.L.; Song, S; Johnson, D; Torres, S.R. (January 1, 2001). "Chronic fatigue syndrome: Comorbidity with fibromyalgia and psychiatric illness". Medicine and Psychiatry. 4: 29–34.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Natelson, Benjamin H. (February 19, 2019). "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Fibromyalgia: Definitions, Similarities, and Differences". Clinical Therapeutics. 41 (4): 612. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.12.016. ISSN 0149-2918. PMID 30795933.

- ↑ Younger, Jarred (May 20, 2016). "Webinar with Jarred Younger, Ph.D." YouTube (Video). SolveCFS. 57:27.

- ↑ Carruthers, Bruce M.; Jain, Anil Kumar; De Meirleir, Kenny L.; Peterson, Daniel L.; Klimas, Nancy G.; Lerner, A. Martin; Bested, Alison C.; Flor-Henry, Pierre; Joshi, Pradip; Powles, AC Peter; Sherkey, Jeffrey A.; van de Sande, Marjorie I. (2003), "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Clinical Working Case Definition, Diagnostic and Treatment Protocols" (PDF), Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, 11 (2): 7–115, doi:10.1300/J092v11n01_02

- ↑ "Bragee Bertilson et al. - ME CFS and Intracranial Hypertension". Center for Open Science. November 27, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ↑ 24.00 24.01 24.02 24.03 24.04 24.05 24.06 24.07 24.08 24.09 24.10 24.11 24.12 24.13 Jahan, Firdous; Nanji, Kashmira; Qidwai, Waris; Qasim, Rizwan (2012). "Fibromyalgia Syndrome: An Overview of Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management". Oman Medical Journal. 27 (3): 192–195. doi:10.5001/omj.2012.44. ISSN 1999-768X. PMID 22811766.

- ↑ "Ask the Doctors: Is Fibromyalgia Progressive?". National Pain Report. August 9, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Alciati, A.; Sgiarovello, P.; Atzeni, F.; Sarzi-Puttini, P. (September 28, 2012). "Psychiatric problems in fibromyalgia: clinical and neurobiological links between mood disorders and fibromyalgia" (PDF). Reumatismo. 64 (4): 268–274. doi:10.4081/reumatismo.2012.268. ISSN 0048-7449. PMID 23024971.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 27.6 "Fibromyalgia". American College of Rheumatology. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Garrick, Nancy. "Fibromyalgia What Causes it?". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ↑ Cooper, Celeste (May 8, 2015). "The Difference Between Fibromyalgia Tender Points and Myofascial Trigger Points - Chronic Pain | HealthCentral". healthcentral.com. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ↑ "How Is Fibromyalgia Diagnosed?". WebMD. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 Proskauer, Charmian (February 5, 2011). "Tender Points might no longer be used for diagnosis of Fibromyalgia". Massachusetts ME/CFS & FM Association. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "2016 Revisions to the 2010/2011 Fibromyalgia Diagnostic Criteria - ACR Meeting Abstracts". ACR Meeting Abstracts. September 28, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ↑ Bennett, Robert M.; Friend, Ronald; Marcus, Dawn; Bernstein, Cheryl; Han, Bobby Kwanghoon; Yachoui, Ralph; Deodhar, Atul; Kaell, Alan; Bonafede, Peter (2014). "Criteria for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia: validation of the modified 2010 preliminary American College of Rheumatology criteria and the development of alternative criteria". Arthritis Care & Research. 66 (9): 1364–1373. doi:10.1002/acr.22301. ISSN 2151-4658. PMID 24497443.

- ↑ "How Fibromyalgia Affects Men: Symptoms and Diagnosis". WebMD. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 Kaltsas, Gregory; Tsiveriotis, Konstantinos (2000). "Fibromyalgia". In Feingold, Kenneth R.; Anawalt, Bradley; Boyce, Alison; Chrousos, George; de Herder, Wouter W.; Dhatariya, Ketan; Dungan, Kathleen; Hershman, Jerome M.; Hofland, Johannes (eds.). Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc. PMID 25905317.

- ↑ ORDP; OPPS (July 25, 2012). "Social Security Ruling: SSR 12-2p". ssa.gov. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Hackshaw, Kevin V. (February 2021). "The Search for Biomarkers in Fibromyalgia". Diagnostics. 11 (2): 156. doi:10.3390/diagnostics11020156. PMC 7911687. PMID 33494476.

- ↑ Hashmi, Javeria (March 11, 2020). "Brain Imaging Study on Biomarkers for Fibromyalgia". Nova Scotia Health Authority.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 López-Solà, Marina; Woo, Choong-Wan; Pujol, Jesus; Deus, Joan; Harrison, Ben J.; Monfort, Jordi; Wager, Tor D. (2017). "Towards a neurophysiological signature for fibromyalgia". Pain. 158 (1): 34–47. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000707. ISSN 1872-6623. PMID 27583567.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Gracely, Richard H.; Petzke, Frank; Wolf, Julie M.; Clauw, Daniel J. (2002). "Functional magnetic resonance imaging evidence of augmented pain processing in fibromyalgia". Arthritis & Rheumatism. 46 (5): 1333–1343. doi:10.1002/art.10225. ISSN 1529-0131.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Loggia, Marco L.; Chonde, Daniel B.; Akeju, Oluwaseun; Arabasz, Grae; Catana, Ciprian; Edwards, Robert R.; Hill, Elena; Hsu, Shirley; Izquierdo-Garcia, David (January 8, 2015). "Evidence for brain glial activation in chronic pain patients". Brain. 138 (3): 604–615. doi:10.1093/brain/awu377. ISSN 1460-2156.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Boodman, Eric (October 20, 2021). "In a sea of skeptics, this physician was one of fibromyalgia patients' few true allies. Or was he?". STAT News.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 "Home". EpicGenetics' FM/a® Test is FDA-compliant and has successfully diagnosed patients with fibromyalgia since 2012. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 Faustman, Denise Louise (May 27, 2021). "Phase II Clinical Trial: Multi-dosing the BCG Vaccine for Fibromyalgia". Massachusetts General Hospital. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Behm, Frederick G; Gavin, Igor M; Karpenko, Oleksiy; Lindgren, Valerie; Gaitonde, Sujata; Gashkoff, Peter A; Gillis, Bruce S (December 17, 2012). "Unique immunologic patterns in fibromyalgia". BMC Clinical Pathology. 12: 25. doi:10.1186/1472-6890-12-25. ISSN 1472-6890. PMC 3534336. PMID 23245186.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Wallace, Daniel J.; Gavin, Igor M.; Karpenko, Oleksly; Barkhordar, Farnaz; Gillis, Bruce S. (2015). "Cytokine and chemokine profiles in fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus: a potentially useful tool in differential diagnosis". Rheumatology International. 35 (6): 991–996. doi:10.1007/s00296-014-3172-2. ISSN 0172-8172. PMC 4435905. PMID 25377646.

- ↑ Garcia-Martin, Elena; Garcia-Campayo, Javier; Puebla-Guedea, Marta; Ascaso, Francisco J.; Roca, Miguel; Gutierrez-Ruiz, Fernando; Vilades, Elisa; Polo, Vicente; Larrosa, Jose M. (September 1, 2016). "Fibromyalgia Is Correlated with Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thinning". PLoS ONE. 11 (9): e0161574. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0161574. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5008644. PMID 27584145.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Cordón, B.; Orduna, E.; Viladés, E.; Garcia-Martin, E.; Garcia-Campayo, J.; Puebla-Guedea, M.; Polo, V.; Larrosa, J.M.; Pablo, L.E. (July 2, 2021). "Analysis of Retinal Layers in Fibromyalgia Patients with Premium Protocol in Optical Tomography Coherence and Quality of Life". Current Eye Research. 0 (0): 1–11. doi:10.1080/02713683.2021.1951301. ISSN 0271-3683. PMID 34213409.

- ↑ Hackshaw, Kevin V.; Aykas, Didem P.; Sigurdson, Gregory T.; Plans, Marcal; Madiai, Francesca; Yu, Lianbo; Buffington, Charles A.T.; Giusti, M. Mónica; Rodriguez-Saona, Luis (February 15, 2019). "Metabolic fingerprinting for diagnosis of fibromyalgia and other rheumatologic disorders". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 294 (7): 2555–2568. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA118.005816. ISSN 0021-9258.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 World Health Organization (2016). "ICD-10 Version:2016". World Health Organization. M79.7 Fibromyalgia. Retrieved September 15, 2018.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 World Health Organization (2018). "2018 ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Code M79.7: Fibromyalgia". icd10data.com. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ↑ Liptan, Ginevra (September 30, 2015). "The Health Care Industry Finally Recognizes Fibromyalgia". National Pain Report. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 "ICD-11 - Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". World Health Organization. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Bhargava, Juhi; Hurley, John A. (2021). Fibromyalgia. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31082018.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 55.3 Häuser, Winfried; Perrot, Serge; Sommer, Claudia; Shir, Yoram; Fitzcharles, Mary-Ann (2017). "Diagnostic confounders of chronic widespread pain: not always fibromyalgia". Pain Rep. 2 (3): e598. doi:10.1097/PR9.0000000000000598. PMC 5741304. PMID 29392213.

- ↑ "What is Fibromyalgia?". Open Medicine Foundation. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Zhang, Zhifang; Feng, Jinong; Mao, Allen; Le, Keith; Placa, Deirdre La; Wu, Xiwei; Longmate, Jeffrey; Marek, Claudia; Amand, R. Paul St (June 21, 2018). "SNPs in inflammatory genes CCL11, CCL4 and MEFV in a fibromyalgia family study". PLOS ONE. 13 (6): e0198625. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198625. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 29927949.

- ↑ Wolfe, Frederick; Walitt, Brian; Rasker, Johannes J.; Häuser, Winfried (July 15, 2018). "Primary and Secondary Fibromyalgia Are The Same: The Universality of Polysymptomatic Distress". The Journal of Rheumatology. 46 (2): 204–212. doi:10.3899/jrheum.180083. ISSN 0315-162X. PMID 30008459.

- ↑ Gregory Burch, Donna (April 24, 2017). "New UAB Study Could Radically Change Fibromyalgia Treatment As We Know It". National Pain Report. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ↑ Younger, Jarred (May 24, 2017). "Testing the fibromyalgia immune system with lipopolysaccharide (LPS)". YouTube – via Younger Lab.

- ↑ Kerkar, Pramod (September 29, 2016). "What is Overactive Immune System | Causes | Symptoms | Treatment". ePainAssist. Retrieved October 4, 2018.

- ↑ "Autoimmune Diseases". WebMD. Retrieved October 4, 2018.

- ↑ Goebel, Andreas; Krock, Emerson; Gentry, Clive; Israel, Mathilde R.; Jurczak, Alexandra; Urbina, Carlos Morado; Sandor, Katalin; Vastani, Nisha; Maurer, Margot (July 7, 2021). "Passive transfer of fibromyalgia symptoms from patients to mice". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 131 (13). doi:10.1172/JCI144201. ISSN 0021-9738.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 "Fibromyalgia may be a condition of the immune system not the brain – study". The Guardian. July 1, 2021. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ↑ Heffez, Dan S.; Ross, Ruth E.; Shade-Zeldow, Yvonne; Kostas, Konstantinos; Shah, Sagar; Gottschalk, Robert; Elias, Dean A.; Shepard, Alan; Leurgans, Sue E. (April 9, 2004). "Clinical evidence for cervical myelopathy due to Chiari malformation and spinal stenosis in a non-randomized group of patients with the diagnosis of fibromyalgia". European Spine Journal. 13 (6): 516–523. doi:10.1007/s00586-004-0672-x. ISSN 0940-6719. PMID 15083352.

- ↑ Heffez, Dan S.; Ross, Ruth E.; Shade-Zeldow, Yvonne; Kostas, Konstantinos; Morrissey, Mary; Elias, Dean A.; Shepard, Alan (2007). "Treatment of cervical myelopathy in patients with the fibromyalgia syndrome: outcomes and implications". European Spine Journal. 16 (9): 1423–1433. doi:10.1007/s00586-007-0366-2. ISSN 0940-6719. PMC 2200733. PMID 17426987.

- ↑ Holman, Andrew (July 1, 2008). "Positional Cervical Spinal Cord Compression and Fibromyalgia: A Novel Comorbidity With Important Diagnostic and Treatment Implications". The Journal of Pain. 9 (7): 613–622. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2008.01.339. ISSN 1526-5900.

- ↑ "Common Misdiagnoses of Fibromyalgia". WebMD. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- ↑ "Fibromyalgia Pain Isn't All In Patient's Heads, New Brain Study Finds". Melissa Kaplan's Chronic Neuroimmune Diseases. 2014. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ↑ Borsook, David; Moulton, Eric A; Schmidt, Karl F; Becerra, Lino R (September 11, 2007). "Neuroimaging Revolutionizes Therapeutic Approaches to Chronic Pain". Molecular Pain. 3 (1): 1744–8069-3-25. doi:10.1186/1744-8069-3-25. ISSN 1744-8069. PMID 17848191.

- ↑ Albrecht, Daniel S.; Forsberg, Anton; Sandstrom, Angelica; Bergan, Courtney; Kadetoff, Diana; Protsenko, Ekaterina; Lampa, Jon; Lee, Yvonne C.; Höglundi, Caroline Olgart (September 14, 2018). Catana, Ciprian; Cervenka, Simon; Akeju, Oluwaseun; Lekander, Mats; Cohen, George; Halldin, Christer; Taylor, Norman; Kim, Minhae; Hooker, Jacob M.; Loggia, Marco L. "Brain glial activation in fibromyalgia – A multi-site positron emission tomography investigation". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2018.09.018. ISSN 0889-1591.

- ↑ Martucci, Katherine T; Weber, Kenneth A; Mackey, Sean C (October 3, 2018). "Altered Cervical Spinal Cord Resting State Activity in Fibromyalgia". Arthritis & Rheumatology. doi:10.1002/art.40746. ISSN 2326-5191.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 73.3 73.4 73.5 DeNoon, Daniel J. "Fibromyalgia Isn't Depression". WebMD. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Üçeyler, Nurcan; Zeller, Daniel; Kahn, Ann-Kathrin; Kewenig, Susanne; Kittel-Schneider, Sarah; Schmid, Annina; Casanova-Molla, Jordi; Reiners, Karlheinz; Sommer, Claudia (March 9, 2013). "Small fibre pathology in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome". Brain. 136 (6): 1857–1867. doi:10.1093/brain/awt053. ISSN 1460-2156.

- ↑ Pappolla, Miguel A.; Manchikanti, Laxmaiah; Candido, Kenneth D.; Grieg, Nigel; Seffinger, Michael; Ahmed, Fauwad; Fang, Xiang; Andersen, Clark; Trescot, Andrea M. (March 2021). "Insulin Resistance is Associated with Central Pain in Patients with Fibromyalgia". Pain Physician. 24 (2): 175–184. ISSN 2150-1149. PMID 33740353.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Yun, Dong Joo; Choi, Han Na; Oh, Gun-Sei (2013). "A Case of Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome Associated with Migraine and Fibromyalgia". The Korean Journal of Pain. 26 (3): 303–306. doi:10.3344/kjp.2013.26.3.303. ISSN 2005-9159. PMID 23862007.

- ↑ Sleurs, David; Tebeka, Sarah; Scognamiglio, Claire; Dubertret, Caroline; Le Strat, Yann (2020). "Comorbidities of self-reported fibromyalgia in United States adults: A cross-sectional study from The National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC-III)". European Journal of Pain. 24 (8): 1471–1483. doi:10.1002/ejp.1585. ISSN 1532-2149.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 78.2 Yunus, Muhammad B. (June 1, 2007). "Fibromyalgia and Overlapping Disorders: The Unifying Concept of Central Sensitivity Syndromes". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 36 (6): 339–356. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.12.009. ISSN 0049-0172.

- ↑ Cöster, Lars; Kendall, Sally; Gerdle, Björn; Henriksson, Chris; Henriksson, Karl G.; Bengtsson, Ann (2008). "Chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain – A comparison of those who meet criteria for fibromyalgia and those who do not". European Journal of Pain. 12 (5): 600–610. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.10.001. ISSN 1532-2149.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Baron, Ralf; Tölle, Thomas R.; Freynhagen, Rainer; Brosz, Mathias; Gockel, Ulrich; Koroschetz, Jana; Rehm, Stefanie E. (June 1, 2010). "A cross-sectional survey of 3035 patients with fibromyalgia: subgroups of patients with typical comorbidities and sensory symptom profiles". Rheumatology. 49 (6): 1146–1152. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keq066. ISSN 1462-0324.

- ↑ Jensen, Troels S; Finnerup, Nanna B (September 1, 2014). "Allodynia and hyperalgesia in neuropathic pain: clinical manifestations and mechanisms". The Lancet Neurology. 13 (9): 924–935. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70102-4. ISSN 1474-4422.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedJensen2010 - ↑ "Peripheral Neuropathy -- Symptoms, Types, and Causes of Peripheral Neuropathy". WebMD. p. 3. Retrieved October 4, 2018.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 84.2 Gore, Mugdha; Tai, Kei-Sing; Chandran, Arthi; Zlateva, Gergana; Leslie, Douglas (October 20, 2011). "Clinical comorbidities, treatment patterns, and healthcare costs among patients with fibromyalgia newly prescribed pregabalin or duloxetine in usual care". Journal of Medical Economics. 15 (1): 19–31. doi:10.3111/13696998.2011.629262. ISSN 1369-6998.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 85.2 Park, Denise C.; Glass, Jennifer M.; Minear, Meredith; Crofford, Leslie J. (2001). "Cognitive function in fibromyalgia patients". Arthritis & Rheumatism. 44 (9): 2125–2133. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(200109)44:9<2125::AID-ART365>3.0.CO;2-1. ISSN 1529-0131.

- ↑ Wu, Yu-Lin; Huang, Chun-Jen; Fang, Su-Chen; Ko, Ling-Hsin; Tsai, Pei-Shan (2018). "Cognitive Impairment in Fibromyalgia: A Meta-Analysis of Case-Control Studies". Psychosomatic medicine. 80 (5): 432–438. PMID 29528888.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 87.2 Kratz, Anna L.; Schilling, Stephen; Goesling, Jenna; Williams, David A. (June 2015). "Development and Initial Validation of a Brief Self-Report Measure of Cognitive Dysfunction in Fibromyalgia". The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 16 (6): 527–536. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2015.02.008. ISSN 1526-5900. PMC 4456217. PMID 25746197.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 Bell, Tyler Reed; Trost, Zina; Buelow, Melissa T.; Clay, Olivio; Younger, Jarred; Moore, David; Crowe, Michael (September 2018). "Meta-analysis of cognitive performance in fibromyalgia". Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology. 40 (7): 698–714. doi:10.1080/13803395.2017.1422699. ISSN 1380-3395. PMC 6151134. PMID 29388512.

- ↑ "Fibromyalgia and Depression". WebMD. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ↑ Koroschetz, Jana; Rehm, Stefanie E.; Gockel, Ulrich; Brosz, Mathias; Freynhagen, Rainer; Tölle, Thomas R.; Baron, Ralf (May 25, 2011). "Fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain - differences and similarities. A comparison of 3057 patients with diabetic painful neuropathy and fibromyalgia". BMC Neurology. 11 (1): 55. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-11-55. ISSN 1471-2377. PMC 3125308. PMID 21612589.

- ↑ Müller, W.; Schneider, E.M.; Stratz, T. (September 1, 2007). "The classification of fibromyalgia syndrome". Rheumatology International. 27 (11): 1005–1010. doi:10.1007/s00296-007-0403-9. ISSN 1437-160X.

- ↑ "Sjogren's syndrome - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ↑ US Department of Veterans Affairs. "Fibromyalgia in Gulf War Veterans - Public Health". Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ↑ Nickel, J. Curtis; Tripp, Dean A.; Pontari, Michel; Moldwin, Robert; Mayer, Robert; Carr, Lesley K.; Doggweiler, Ragi; Yang, Claire C.; Mishra, Nagendra (2010). "Interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome and associated medical conditions with an emphasis on irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome". The Journal of Urology. 184 (4): 1358–1363. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.005. ISSN 1527-3792. PMID 20719340.

- ↑ Teodoro, Tiago; Edwards, Mark J.; Isaacs, Jeremy D. (December 1, 2018). "A unifying theory for cognitive abnormalities in functional neurological disorders, fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome: systematic review" (PDF). Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 89 (12): 1308–1319. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2017-317823. ISSN 0022-3050. PMID 29735513.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 Afrin, Lawrence B.; Ackerley, Mary B.; Bluestein, Linda S.; Brewer, Joseph H.; Brook, Jill B.; Buchanan, Ariana D.; Cuni, Jill R.; Davey, William P.; Dempsey, Tania T.; Dorff, Shanda R.; Dubravec, Martin S. (May 1, 2021). "Diagnosis of mast cell activation syndrome: a global "consensus-2"". Diagnosis. 8 (2): 137–152. doi:10.1515/dx-2020-0005. ISSN 2194-802X.

- ↑ Valent, Peter; Akin, Cem (April 1, 2019). "Doctor, I Think I Am Suffering from MCAS: Differential Diagnosis and Separating Facts from Fiction". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 7 (4): 1109–1114. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2018.11.045. ISSN 2213-2198. PMID 30961836.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 Schertzinger, Meredith; Wesson-Sides, Kate; Parkitny, Luke; Younger, Jarred (April 1, 2018). "Daily Fluctuations of Progesterone and Testosterone Are Associated With Fibromyalgia Pain Severity". The Journal of Pain. 19 (4): 410–417. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2017.11.013. ISSN 1526-5900. PMID 29248511.

- ↑ "Migraines and Fibromyalgia - Migraine Centers". Migraine Centers. May 6, 2016. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ↑ Slotkoff, A.T.; Radulovic, D.A.; Clauw, D.J. (January 1, 1997). "The Relationship between Fibromyalgia and the Multiple Chemical Sensitivity Syndrome". Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 26 (5): 364–367. doi:10.3109/03009749709065700. ISSN 0300-9742. PMID 9385348.

- ↑ Hudson, J.I.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Pope, H.G.; Keck, P.E.; Schlesinger, L. (April 1992). "Comorbidity of fibromyalgia with medical and psychiatric disorders". The American Journal of Medicine. 92 (4): 363–367. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(92)90265-d. ISSN 0002-9343. PMID 1558082.

- ↑ Slotkoff, A.T.; Radulovic, D.A.; Clauw, D.J. (January 1, 1997). "The Relationship between Fibromyalgia and the Multiple Chemical Sensitivity Syndrome". Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 26 (5): 364–367. doi:10.3109/03009749709065700. ISSN 0300-9742. PMID 9385348.

- ↑ Donnay, Albert; Ziem, Grace (January 1, 1999). "Prevalence and Overlap of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Fibromyalgia Syndrome Among 100 New Patients with Multiple Chemical Sensitivity Syndrome". Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 5 (3–4): 71–80. doi:10.1300/J092v05n03_06. ISSN 1057-3321.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 D'Onghia, Martina; Ciaffi, Jacopo; Lisi, Lucia; Mancarella, Luana; Ricci, Susanna; Stefanelli, Nicola; Meliconi, Riccardo; Ursini, Francesco (April 1, 2021). "Fibromyalgia and obesity: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 51 (2): 409–424. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2021.02.007. ISSN 0049-0172.

- ↑ "Vulvodynia - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ↑ Pamuk, Ömer Nuri; Dönmez, Salim; Çakir, Necati (May 1, 2009). "Increased frequencies of hysterectomy and early menopause in fibromyalgia patients: a comparative study". Clinical Rheumatology. 28 (5): 561–564. doi:10.1007/s10067-009-1087-1. ISSN 1434-9949.

- ↑ Santoro, Maya S.; Cronan, Terry A.; Adams, Rebecca N.; Kothari, Dhwani J. (November 2012). "Fibromyalgia and hysterectomy: the impact on health status and health care costs". Clinical Rheumatology. 31 (11): 1585–1589. doi:10.1007/s10067-012-2051-z. ISSN 1434-9949. PMID 22875702.

- ↑ Brooks, Larry; Hadi, Joseph; Amber, Kyle T; Weiner, Michelle; La Riche, Christopher L; Ference, Tamar (August 20, 2015). "Assessing the prevalence of autoimmune, endocrine, gynecologic, and psychiatric comorbidities in an ethnically diverse cohort of female fibromyalgia patients: does the time from hysterectomy provide a clue?". Journal of Pain Research. 8: 561–569. doi:10.2147/JPR.S86573. ISSN 1178-7090. PMC 4548754. PMID 26316807.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 Magtanong, Glenda Gatan; Spence, Andrea R.; Czuzoj-Shulman, Nicholas; Abenhaim, Haim Arie (February 1, 2019). "Maternal and neonatal outcomes among pregnant women with fibromyalgia: a population-based study of 12 million births". The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 32 (3): 404–410. doi:10.1080/14767058.2017.1381684. ISSN 1476-7058. PMID 28954564.

- ↑ Lapp, Charles W.; Black, Laura; Smith, Rebekah S. "Symptoms Predict the Outcome of Tilt Table Testing in CFS/ME/FM" (PDF). drlapp.com.

- ↑ Zamunér, Antonio Roberto; Porta, Alberto; Andrade, Carolina Pieroni; Forti, Meire; Marchi, Andrea; Furlan, Raffaello; Barbic, Franca; Catai, Aparecida Maria; Silva, Ester (June 14, 2017). "The degree of cardiac baroreflex involvement during active standing is associated with the quality of life in fibromyalgia patients". PLoS ONE. 12 (6): e0179500. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0179500. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5470709. PMID 28614420.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 Shah, Rinoo V.; Kaye, Alan D. (October 10, 2011). "Gynecological, Pelvic, and Urological Pain". In Kaye, Alan D.; Urman, Richard D. (eds.). Understanding Pain: What You Need to Know to Take Control. ABC-CLIO. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-313-39604-5.

- ↑ "Reynauld's disease - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ↑ Pauling, John D.; Hughes, Michael; Pope, Janet E. (December 1, 2019). "Raynaud's phenomenon—an update on diagnosis, classification and management". Clinical Rheumatology. 38 (12): 3317–3330. doi:10.1007/s10067-019-04745-5. ISSN 1434-9949.

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 Vatthauer, Karlyn E; Craggs, Jason G; Robinson, Michael E; Staud, Roland; Berry, Richard B; Perlstein, William M; McCrae, Christina S (November 12, 2015). "Sleep is associated with task-negative brain activity in fibromyalgia participants with comorbid chronic insomnia". Journal of Pain Research. 8: 819–827. doi:10.2147/JPR.S87501. ISSN 1178-7090. PMID 26648751.

- ↑ "Temporomandibular disorder". John Hopkins Medicine. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ↑ Soares Gui, Maisa; Pimentel, Marcele Jardim; Rizzatti-Barbosa, C'elia Marisa (March 1, 2015). "Temporomandibular disorders in fibromyalgia syndrome: a short-communication". Revista Brasileira de Reumatologia (English Edition). 55 (2): 189–194. doi:10.1016/j.rbre.2014.07.004. ISSN 2255-5021 – via ScienceDirect.

- ↑ "Hashimoto's Thyroiditis". American Thyroid Association. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ↑ Arnold, Lesley M.; Clauw, Daniel J.; Dunegan, L. Jean; Turk, Dennis C. (2012). "A Framework for Fibromyalgia Management for Primary Care Providers". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 87 (5): 488–496. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.02.010. ISSN 0025-6196.

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 Ronenn, Roubenoff. "Fibromyalgia Exercise | Exercising with Fibromyalgia". arthritis.org. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ↑ Bidonde, Julia; Busch, Angela J.; Webber, Sandra C.; Schachter, Candice L.; Danyliw, Adrienne; Overend, Tom J.; Richards, Rachel S.; Rader, Tamara (October 28, 2014). "Aquatic exercise training for fibromyalgia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD011336. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011336. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 25350761.

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 Bennett, Robert M.; Jones, Jessie; Turk, Dennis C.; Russell, I. Jon; Matallana, Lynne (March 9, 2007). "An internet survey of 2,596 people with fibromyalgia". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 8 (1): 27. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-8-27. ISSN 1471-2474. PMC 1829161. PMID 17349056.