Autonomic nervous system

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is the branch of the peripheral nervous system that allows for communication between the internal organs and the brain, and is responsible for regulating many involuntary processes in the body. The ANS's sympathetic nervous system is constantly active, responding to information from an individual’s environment and his or her body to regulate functions such as heart rate, breathing, and digestion.[1][2][3]

Function

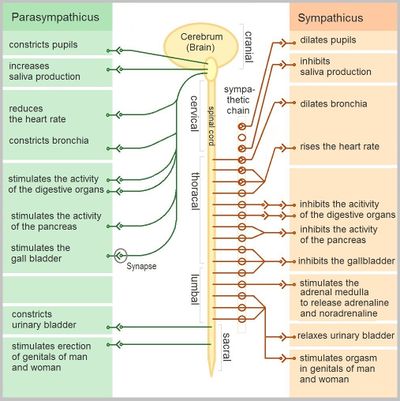

The ANS is split into two main divisions: the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and parasympathetic nervous system (PNS). The PNS and SNS serve the same organs, but one system will activate a bodily function while the other will inhibit it.[3] This opposition is operated by two main chemical messengers: norepinephrine, which activates (excitatory) and acetylcholine, which inhibits (inhibitory).[1] The two divisions complement each other to regulate the body’s responses.[3] Functions regulated by the ANS include:

- Blood pressure

- Body temperature

- Digestion and hunger

- Emotional responses

- Heart rate

- Metabolism

- Production of sweat, saliva

- Respiratory rate

- Sexual response

- Urination[1][2]

Sympathetic nervous system

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) regulates what is referred to as the “fight-or-flight” response, which prepares the body against a perceived stress or threat. Stimulation of the SNS activates an internal alarm response. This causes an increase in:

- Heart rate (more blood pumped throughout the body)

- Muscle strength

- Width of airways (maximizing the intake of oxygen/elimination of carbon dioxide)

- The release of stored energy

During perceived physiological or emotional stress, the SNS is activated while the PNS is less predominant. This redirects the body’s resources toward processes that are important in an emergency situation, resulting in a decrease in bodily functions controlled by the PNS, which are less important in an emergency situation.[1]

Parasympathetic nervous system

The parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) is dominant in conditions referred to as “rest and digest”. It controls body processes during ordinary situations. This division of the ANS helps return the body to resting state after confronting a stressor, helping to conserve energy.[1]

Functions of the PNS include:

- Contraction of the bladder

- Reducing blood pressure[1][2]

- Slowing heart rate

- Stimulating the digestive tract, including gland secretion

Autonomic disorder and dysfunction

Symptoms of autonomic dysfunction include:

- Alterations in sweating, resulting in heat intolerance

- Constipation or loss of bowel control

- Exercise intolerance: inability to regulate heart rate during exercise

- Gastroparesis: feeling prematurely full due to slow emptying of stomach

- Hyperactive bladder or hypoactive bladder

- Orthostatic intolerance: dizziness or light-headedness when a person stands up due to a significant decrease in blood pressure, which if severe can lead to syncope (fainting), attributed to cardiovascular deconditioning and/or postural idiopathic autonomic neuropathy

- Sexual response problems (in men and women)

- Vision problems: inability of pupils to react to light quickly, blurred vision[2][3]

Myalgic encephalomyelitis and the ANS

Altered ANS functioning has been seen in many myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) patients, as they experience various altered autonomic responses. Symptoms of autonomic dysfunction in ME include:

- Blood pressure

- Delayed gastric emptying[4]

- Elevated baseline heart rate in some studies[5]

- Body temperature

- Rhermostatic instability/impaired thermoregulation, including significantly increased shivering and sweating episodes compared to controls[6][7]

- Reduced capacity to recover from exercise-induced muscle acidosis (can be attributed to dysfunction of vascular runoff, in part controlled by the ANS)[8][6]

- Digestion

- Increased gut-intestinal permeability (dysfunction of the PNS via abnormal glandular secretion in digestion)[9]

- Exercise intolerance

- Heart rate

- Higher prevalence and severity of POTS[5]

- Impaired blood pressure variability[10]

- Orthostatic intolerance[5][11]

- Reduced heart rate variability at night[12]

- Reduced left ventricular mass, end-diastolic volume and cardiac output, and increased residual torsion in diastole[8]

- Neurological correlates with ANS dysfunction

The vagus nerve hypothesis

The vagus nerve hypothesis suggests that infection and inflammation of the vagus nerve, a prominent nerve within the ANS, would disrupt normal autonomic function. The vagus nerve communicates information between numerous internal organs and the brain. Infection of the vagus nerve could signal an exaggerated sickness response and perpetuate further dysfunction.[14]

See also

Learn more

- Anatomy, Autonomic Nervous System - Statpearls book

- Crash Course | Autonomic Nervous System

- Crash Course | Parasympathetic Nervous System

- Crash Course | Sympathetic Nervous System

- Physiology, Autonomic Nervous System - Statpearls book

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 McCorry, Laurie Kelly (August 15, 2007). "Physiology of the Autonomic Nervous System". American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 71 (4). ISSN 0002-9459. PMID 17786266.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Overview of the Autonomic Nervous System - Brain, Spinal Cord, and Nerve Disorders". Merck Manuals Consumer Version. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Waxenbaum, Joshua A.; Reddy, Vamsi; Varacallo, Matthew (2021). Anatomy, Autonomic Nervous System. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30969667.

- ↑ Burnet, Richard B; Chatterton, Barry E (December 2004). "Gastric emptying is slow in chronic fatigue syndrome". BMC Gastroenterology. 4 (1). doi:10.1186/1471-230x-4-32. ISSN 1471-230X.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Van Cauwenbergh, Deborah; Nijs, Jo; Kos, Daphne; Van Weijnen, Laura; Struyf, Filip; Meeus, Mira (April 17, 2014). "Malfunctioning of the autonomic nervous system in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic literature review". European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 44 (5): 516–526. doi:10.1111/eci.12256. ISSN 0014-2972.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Carruthers, BM; van de Sande, MI; De Meirleir, KL; Klimas, NG; Broderick, G; Mitchell, T; Staines, D; Powles, ACP; Speight, N; Vallings, R; Bateman, L; Bell, DS; Carlo-Stella, N; Chia, J; Darragh, A; Gerken, A; Jo, D; Lewis, DP; Light, AR; Light, KC; Marshall-Gradisnik, S; McLaren-Howard, J; Mena, I; Miwa, K; Murovska, M; Stevens, SR (2012), Myalgic encephalomyelitis: Adult & Paediatric: International Consensus Primer for Medical Practitioners (PDF), ISBN 978-0-9739335-3-6

- ↑ Wyller, Vegard Bruun; Godang, Kristin; Mørkrid, Lars; Saul, Jerome Philip; Thaulow, Erik; Walløe, Lars (July 1, 2007). "Abnormal Thermoregulatory Responses in Adolescents With Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Relation to Clinical Symptoms". Pediatrics. 120 (1): e129–e137. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2759. ISSN 0031-4005.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Jones, David E.J.; Hollingsworth, Kieren G.; Jakovljevic, Djordje G.; Fattakhova, Gulnar; Pairman, Jessie; Blamire, Andrew M.; Trenell, Michael I.; Newton, Julia L. (July 12, 2011). "Loss of capacity to recover from acidosis on repeat exercise in chronic fatigue syndrome: a case-control study". European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 42 (2): 186–194. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2011.02567.x. ISSN 0014-2972.

- ↑ Maes, Michael; Mihaylova, Ivana; Leunis, Jean-Claude (April 2007). "Increased serum IgA and IgM against LPS of enterobacteria in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS): indication for the involvement of gram-negative enterobacteria in the etiology of CFS and for the presence of an increased gut-intestinal permeability". Journal of Affective Disorders. 99 (1–3): 237–240. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.08.021. ISSN 0165-0327. PMID 17007934.

- ↑ Frith, J.; Zalewski, P.; Klawe, J.J.; Pairman, J.; Bitner, A.; Tafil-Klawe, M.; Newton, J.L. (September 2012). "Impaired blood pressure variability in chronic fatigue syndrome--a potential biomarker". QJM: monthly journal of the Association of Physicians. 105 (9): 831–838. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcs085. ISSN 1460-2393. PMID 22670061.

- ↑ Rowe, Peter C.; Lucas, Katherine E. (March 2007). "Orthostatic Intolerance in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome". The American Journal of Medicine. 120 (3): e13. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.033. ISSN 0002-9343.

- ↑ "Heart rate variability in patients with fibromyalgia and patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: A systematic review". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 43 (2): 279–287. October 1, 2013. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.03.004. ISSN 0049-0172.

- ↑ Barnden, Leighton R.; Kwiatek, Richard; Crouch, Benjamin; Burnet, Richard; Del Fante, Peter (January 1, 2016). "Autonomic correlations with MRI are abnormal in the brainstem vasomotor centre in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome". NeuroImage: Clinical. 11: 530–537. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2016.03.017. ISSN 2213-1582.

- ↑ VanElzakker, Michael B. (September 2013). "Chronic fatigue syndrome from vagus nerve infection: a psychoneuroimmunological hypothesis". Medical Hypotheses. 81 (3): 414–423. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2013.05.034. ISSN 1532-2777. PMID 23790471.