Migraine

Migraine is believed to be highly comorbid in people with ME/CFS[1]. As many as 85% of people with ME/CFS may also have migraine disease.

Migraine is a spectrum neurobiological disease with a genetic predisposition. It is the dysfunction of the central and peripheral nervous systems. There are many different types & subtypes of migraine. If not properly managed, migraine can be a progressive, ongoing disease.

In a 2011 study by Ravindran, et al, migraine were found in 84%, and tension-type headaches in 81% of a cohort of chronic fatigue syndrome patients.[2] This compared to 5% and 45%, respectively, in a cohort of healthy controls.[2] Receiving a migraine diagnosis and appropriately treating the disease may reduce overall symptoms and stress that could trigger post-exertional malaise.

Symptoms

Migraine symptoms include mild to moderate unilateral and/or throbbing or pulsating headache that may get worse with or lead to the avoidance of physicial activity (such as doing laundry, etc). Migraine pain is described as moderate to severe, but some types of migraine have little to no head pain.

According to diagnostic criteria, other symptoms include light and/or sound sensitivity, as well as nausea and/or vomiting. The majority of migraine patients will experience allodynia during their attack.

Migraine makes one incredibly sensitive to sensory & environmental stimuli that many call triggers. Triggers do not cause migraine disease; migraine disease makes one sensitive to triggers.

Phases

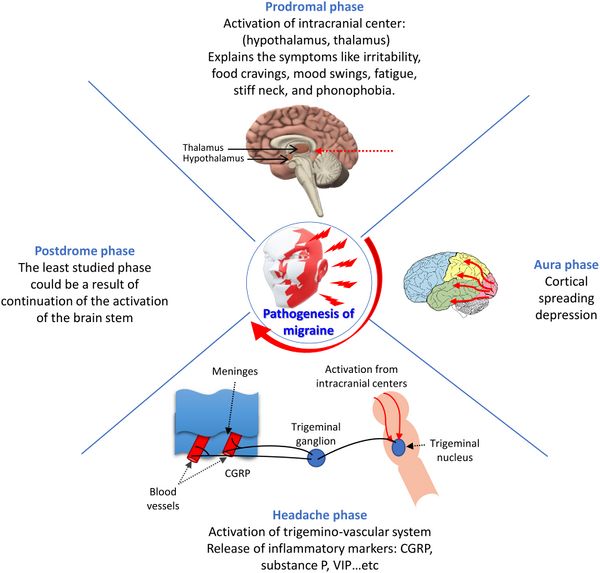

Migraine has 4-5 phases: prodromal, aura (for 30% of migraine patients), acute, postdrome, and interictal (between attacks). Many with chronic migraine experience ongoing migrainous symptoms between attacks.

- Prodromal (pre-headache) stage

- 4-42 hours before the aura or acute phase. Symptoms include phantom smells, heightened sensory sensitivity (smells, sounds, visual stimuli), food cravings, neck pain, increased urination, increased energy, etc.

- Recent research shows that many prodromal symptoms may be confused for migraine attack triggers.

- Aura phase (~30% of migraine population)

- 5-60 minutes before the acute phase. Outside of migraine with brainstem aura, auras typically are experienced sequentially, fully reversing before transitioning to the next aura. This is due to how cortical spreading depression works by slowly traveling across various cortexes of the brain.

- The majority of people with migraine with aura experience visual aura: flashes of light (scintillations), blind spots (scotoma), perceiving objects to be much larger or smaller than in reality, shimmering, flickering, tunnel vision, and blurred/distorted vision.

- Other auras include somatosensory (tingling, pins & needles, numbness, feeling like a limb is disconnected), dysphasic (mixing up words, difficulty thinking of words, slurred speech, stutter, difficulty understanding speech), vestibular (dizziness, vertigo, spacial disorientation), and motor (motor weakness, facial droop, dexterity issues, sensation of dead weight).

- Anecdotally, people have reported olfactory & taste-related auras but those are not acknowledged by the International Classification of Headache Disorders, Third Edition (ICHD-3).

- Acute phase

- Typically a moderate or severe pulsating or throbbing head pain on one side of the head (but can be on both sides), often accompanied by nausea, vomiting or extreme light sensitivity and extreme sensitivity to loud sounds, which last from 4 hours to 3 days without acute medication.

- For the majority of people with migraine, allodynia (a sign of central sensitization) begins during the acute phase.

- For those with vestibular migraine, the acute phase consists of moderate to severe dizziness, in addition to the more traditional head pain, nausea, vomiting, and severe sensory sensitivities (particularly motion & screens).

- Postdromal stage

- Often referred to the hangover phase, the postdrome is when acute and other symptoms gradually fade, but there may be tiredness & exhaustion for few days after[4][5][3] Not every migraine patient experiences the postdrome.

- Additional symptoms may include brain fog, mood changes, sensory sensitivities, dull head pain, GI & urinary issues, temperature dysregulation, allodynia, and more.

- Interictal Phase

- Otherwise known as the phase between migraine attacks. For many, the interictal phase will be symptom-free, but for most with chronic migraine, vestibular migraine, or migraine with unilateral motor symptoms (MUMS), the interictal phase may include ongoing symptoms including dull headache, sensory sensitivities (light, sound, temperature, motion, etc), and other neurological symptoms. [6]Those with chronic vestibular migraine typically experience ongoing baseline dizziness, and those with chronic MUMS may experience ongoing baseline unilateral weakness, tingling, & dysfunctioning proprioception.[7]

Source: Khan et. al. (2021). Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 139, 111557.[5]

Types

Migraine without aura

Migraine without aura is defined by the following diagnostic criteria outlined in The International Classification Of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition[8]:

Migraine without aura diagnostic criteria

- At least five headache attacks that

- Last 4–72 hours without successful treatment

- Headaches have at least two of the following four characteristics:

- unilateral location;

- pulsating quality;

- moderate to severe pain intensity; and

- aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity.

- During the headaches at least one of the following:

- nausea and/or vomiting

- photophobia and phonophobia (avoidance of loud noises)

- Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis.

- Migraines without aura may also be called common migraine or hemicrania simplex'.[9]

Migraine with aura

Migraine with aura diagnostic criteria

- Visual, sensory and central nervous system symptom in beginning shortly before a migraine headache are known as an aura, although migraine with aura without migraine headaches are also recognized.

- At least two migraine attacks fulfilling criteria B and C

- One or more of the following fully reversible aura symptoms

- visual

- sensory

- speech and/or language

- motor

- brainstem

- retinal

- At least three of the following characteristics:

- at least one aura symptom spreads gradually over five minutes or longer

- two or more aura symptoms occur in succession

- each individual aura symptom lasts 5 to 60 minutes

- at least one aura symptom is unilateral (one sided)

- at least one aura symptom is positive

- the aura is accompanied, or followed within 60 minutes, by headache

- Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis.[9]

The recognized types of migraine with aura are:

- Typical aura with headache

- Typical aura without headache

- Migraine with brainstem aura

- Hemiplegic migraine, including familial hemiplegic migraine (FHM) type 1, type 2, type 3 and with other loci

- Sporadic hemiplegic migraine (SHM)

- Retinal migraine

Migraines without aura may also be called Classic or classical migraine, ophthalmic, hemiparaesthetic, hemiplegic or aphasic migraine, or complicated migraine.[9]

Note: Ocular and complex migraine are not official terms. Ocular migraine is used interchangeably with retinal migraine and migraine with (visual) aura. Retinal migraine is a very specific type of migraine where the aura appears in one eye only and is believed to be due to excitement in the retina. Migraine with visual aura is due to cortical spreading depression taking place in the brain, specifically the visual cortex.

Complex migraine is a catch-all term for migraine with atypical aura, migraine with brainstem aura, migraine with unilateral motor symptoms (MUMS), hemiplegic migraine, and vestibular migraine. Neurologists who use this term may not be well-versed in the specific mechanisms involved in each migraine type, which may lead to inappropriate treatment. [10]

Epidosic vs Chronic migraine[11]

- Very low frequency episodic migraine - 0-3 migraine and/or headache days/month

- Low frequency episodic migraine - 4-7 migraine and/or headache days/month

- High frequency episodic migraine - 8-14 migraine and/or headache days/month

- Chronic migraine - 15 headache days where at least 8 days have migrainous features (light/sound sensitivity, Nausea/vomiting, exacerbation by activity, etc)

Migrainous features can include sensory sensitivity (light, sound, smell, motion), nausea and/or vomiting, exacerbation by activity, neck pain, allodynia, etc. One does not have to have a stereotypical migraine attack to log a migrainous feature day; they can have a dull headache with light sensitivity, tinnitus, and allodynia, and that would count toward a migraine day, although the exact definition of a "migraine day" is still unstandardized by the headache community.

Research does show a significant shift in quality of life as the person transitions from very low frequency episodic migraine to high frequency episodic migraine, which is why preventive treatment is now encouraged to begin when the person experiences 4 migraine and/or headache days in a month.

Note: as migraine progresses, it's symptoms typically become more persistent and neurological and less dominated by pain[12]. This happens because the brain undergoes changes in how it processes pain and sensory information over time. With repeated migraine attacks, the nervous system becomes sensitized and more reactive—not just to pain but to non-painful sensory inputs. Patients are more likely to develop vestibular migraine [13]and MUMS (or both) during this time.

This can lead to:

- A reduction in the intensity of headache pain but an increase in unusual sensory symptoms (like visual disturbances, dizziness, or sensory sensitivities).

- A “normalization” or habituation effect where the brain adapts to frequent pain signals, leading to less intense pain but more complex neurological symptoms.

- Alterations in brain networks related to sensory integration, emotional regulation, and pain modulation, changing the migraine experience qualitatively.

- Changes in neurotransmitter systems and cortical excitability reduce pain perception but increase aura complexity, sensory disturbances, or fatigue.

Migraine with Aura without Head Pain (silent or acephalgic migraine)

Migraine symptoms that do not result in a headache are known as migraine with aura without head pain, e.g. migraine aura symptoms without head pain.migraine aura without headache – where an aura or other migraine symptoms are experienced, but a headache does not develop.[3]

Abdominal migraine

Most often occurring in children, [9] the person must have had at least five recurrent episodes of moderate to severe pain in the abdomen usually around the midsection or belly button. The person must also have at least two of the following: nausea, vomiting, paleness, or loss of appetite. A headache may or may not be present. An aura may occur before the abdominal symptoms.[14]

Other Migraine Types & complications

(either recognized in the ICHD-3 appendix or gathering international headache research support)

- Menstrual migraine or menstrual-related migraine

- Vestibular migraine

- Migraine with Unilateral Motor Symptoms (MUMS)[15]

- Multi-sensory migraine subtypes

- Prolonged aura without infarction

- Persistent migraine aura

Triggers

![Migraine triggers. Source: Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 139, 111557[5]](/w/images/thumb/c/c6/Migraine_triggers.jpg/600px-Migraine_triggers.jpg)

Source: Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 139, 111557[5]

Migraine is a neurological disease with an inherent sensitivity to a wide and ever-changing range of triggers, many of which are unavoidable normal daily environmental or lifestyle factors that become problematic when experienced irregularly or unpredictably.

People with migraine are sensitive to stress, environmental factors, various sensory stimuli, some food, and various changes (hormonals, biochemical) that are called triggers. Research is beginning to support that the brain's altered processing creates a varied vulnerability to varied and unpredictable triggers[16] rather than the previously presented singular trigger cause + effect theory. Migraine management is slowly transitioning away from strict trigger avoidance and toward dynamic trigger management via treatments and lifestyle measures[17].

Migraine & ME/CFS

Migraines is one of several illnesses or conditions common in people with ME/CFS.[18][19]

The Canadian Consensus Criteria recognizes migraines in the possible neurological symptoms of ME/CFS, and the International Consensus Criteria recognizes headache conditions including migraine and tension-type headache in the diagnostic criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis.[19] Though it is important to note that migraine is not a symptom of ME/CFS but instead is a comorbidity that requires its own standalone treatment.

The Relationship and Commonalities Between ME/CFS and Migraine[20]

It is believed central sensitization plays a key role in the connection between ME/CFS and migraine. Central sensitization is also known as hypersensitivity of the nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and causes allodynia and hyperalgesia. Allodynia occurs when someone experiences pain from something not normally painful. Some examples of allodynia are pain from touching cold water, brushing hair or moving the bed sheets across the skin. Hyperalgesia is when someone experiences an increased sensitivity to pain. Hyperalgesia can occur after injury to an area of the body or from opioid usage. Allodynia and hyperalgesia are common symptoms of migraine and ME/CFS which suggests central sensitization may be a key component underlying the physiology between both conditions.

Other commonalities between migraine and ME/CFS include:

- ME/CFS and migraine affect females more than males, although men can develop both diseases.

- Although both diseases have their own criteria for diagnosis, the diagnosis is made based on symptoms and elimination of other causes.

- Many people with ME/CFS or migraine are impacted by exercise, stress or sensitivity to sensory stimulation or changes in barometric pressure.

- They share many comorbidities such as fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, temporomandibular joint disorder, chronic pelvic pain, depression, anxiety and more.

- Chronic pain, chronic migraine and ME/CFS are much more common in people with a history of abuse and PTSD.

Additional resources:

Fatigue, chronic fatigue syndrome and migraine: Intersecting the lines through a cross-sectional study in patients with episodic and chronic migraine[21][22]

Discriminating Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and comorbid conditions using metabolomics in UK Biobank[23]

Migraine Is More Than Just Headache: Is the Link to Chronic Fatigue and Mood Disorders Simply Due to Shared Biological Systems?[24]

Chronic Overlapping Pain Conditions in people with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): a sample from the Multi-site Clinical Assessment of ME/CFS (MCAM) study[25]

Possible causes

Migraine is believed to be genetic, with monogenic and polygenic contributions to its pathophysiology.[26] It is believed to be caused by genetic and epigenetic factors. Migraine also has physiological and biochemical factors, e.g. insulin or oestrogen hormone levels, increased oxidative stress[5][3]

Potential treatments

Migraine treatment consists of:

- Acute therapies that aim to stop a migraine attack or reduce the symptoms: gepants, triptans, NSAIDs, neuromodulation devices, DHE, and anti-nausea medication

- Preventive therapies that manage the disease, including reducing attack frequency and symptom severity.

Considering the high comorbidity rate of migraine in patients with me/cfs, it is increasingly recognized that receiving a migraine diagnosis and appropriately (and likely aggressively) treating migraine will improve the overall outcomes and quality of life of me/cfs patients. If chronic migraine is not identified and treated, these ongoing sensory sensitivities can exacerbate neurological stress and increase the overall burden on the central nervous system. This heightened neural stress may contribute to the worsening of symptoms and triggers post-exertional malaise (PEM)[27], a hallmark and debilitating feature of ME/CFS characterized by worsening of fatigue, pain, and cognitive dysfunction after minimal physical or mental exertion.

Acute migraine treatments

- General pain medications, including acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAID), for mild to moderate migraines. Naproxen is often preferred. Different types of medications are sometimes combined, for example acetaminophen and naproxen.[5]

- Prescription NSAIDs, such as Toradol (Sprix), diclofenac, and nabumetone, flurbiprofen, indomethacin, etc. While not often prescribed, flurbiprofen is one of the most effective NSAIDs and has the strongest effect when treating migraine.

- Triptans or ditans for moderate or severe migraine e.g. sumatriptan (Imitrex): 13 out of 14 newly diagnosed migraine subjects responded to sumatriptan in one CFS patient cohort[2] or zomitriptan (Zomig)[28]

- Small molecule CGRP antagonists, known as gepants, which are the newest group of migraine drugs[29]

- Dihydroergotamine interacts with multiple receptors in the brain, including serotonin, dopamine, and adrenergic receptors, to stop the release of substances that contribute to headache pain and inflammation, as well as central sensitization. DHE can hold promise as an acute ME/CFS option due to how it reduces inflammation and targets central sensitization.

- Antinausea medications - reglan, prochlorperazine, promethazine, and zofran. Note: both reglan & prochlorperazine treat the process of migraine in addition to migraine-associated gastroparesis and dyspepsea.

- Neuromodulation devices treat migraine by applying targeted electrical or magnetic stimulation to specific nerves or brain areas involved in migraine pathophysiology, modulating their activity to reduce pain and prevent attacks. Devices include e-TNS (Cefaly), TENS (HeadATerm), sTMS (savi dual), nVNS (gammaCore or Truvaga), REN (Nerivio), and COT-NS (Relivion).[30]

Migraine preventive and management treatments

Depending on the migraine type, various mechanisms contribute to the disease and its symptoms. Migraine treatments target various mechanisms that are part of migraine pathophysiology.

- CGRP targeting medications, such as CGRP monoclonal antibodies[29] like Amovig, Ajovy, Emgality and Vyepti, as well as gepants, such as Qulipta and Nurtec, that block the CGRP pathway. These medications target calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP), which sensitize trigeminal neurons & lead to the development of allodynia and migraine attacks where normal stimuli can lead to nociceptive sensitizations.

- Botox injections (botulinum toxin type A via the PREEMPT Protocol)

- Off-label medications, including beta blockers (propranolol, etc), anti-seizure medications (topiramate, etc), gabapentinoids, tricyclic antidepressants (Amitriptyline, Nortriptyline), calcium channel blockers (verapamil), sodium channel blockers (lamotrigine, mexiletine), antipsychotics (olanzapine), NMDA-receptor antagonists (Namenda, amantadine, etc). [29][31] These medications do things from block neuronal excitability (NMDA-receptor antagonists) and pain modulation (beta blockers) to reducing neuronal excitability (anti-seizure meds) and reducing cortical spreading depression and hyperexcitability (sodium channel blockers).

- Neuromodulation Devices apply external electrical or magnetic impulses to reduce, eliminate or prevent migraine attacks. They are worn or held against different parts of the body to stimulate nerves or areas of the brain and nervous system involved in the migraine process. Preventive neuromodulation devices include Cefaly, gammaCore, Nerivio, and savi dual. Otolith is completing its clinical trials for vestibular migraine.

- Infusions - outpatient and inpatient infusions typically are used to treat status migrainosus, medication adaptation headache, and refractory chronic migraine. Vyepti is a quarterly CGRP targeting infusion that has been proven to be particularly effective for severe chronic migraine. Other infusions may include ketorolac, dihydroergotamine, lidocaine, ketamine, prochlorperazine, magnesium, antipsychotic medication, and saline.

PACAP-targeting medications currently are in clinical trials and will be released to the public in the coming years.

Complementary Care - these are not standalone treatments but instead may improve ones overall treatment plan and improve quality of life.

- Nerve blocks: trigeminal nerve block, occipital nerve block, SPG block[32]

- Biofeedback [33]

- Green light therapy is a narrow band of green light that generates weaker electrical signals in the brain's pain-processing areas

- FL-41 lenses filter out specific wavelengths of light, primarily in the blue-to-green spectrum (approximately 480 to 520 nm). This range of light has been found to be particularly triggering for people with migraine due to its activation of certain retinal cells called intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs), which influence both visual processing and pain pathways in the brain. This reduces photophobia, as well as eye strain.[34]

- Physical therapy, vestibular rehab therapy, and occupational therapy

- Acupuncture[31]

- Supplements including magnesium, feverfew, the B vitamin riboflavin, CoQ10, and others.[35][36][37] Butterbur is not recommended due to liver toxicity.[38] Some neurologists still recommend supplements with Butterbur as long as they are free of pyrrolizidine alkaloids.

- Daith piercing, a type of ear piercings[39] - there is no reproducible, peer-reviewed evidence supporting daith piercings. Given the migraine population's high rate of the placebo effect, daith piercing success is commonly believed to be placebo effect and somewhat short-lived.

- Migraine elimination diets, which rely on identifying particular foods, drinks or additives that trigger migraines, for example avoiding food or drinks containing nitrates or tyramine[5][31] However more current research shows that trigger avoidance is not as effective as overall dynamic migraine disease management.

Other recommended measures include meditation, mindfulness, progressive muscle relaxation, sleep hygiene, stress reduction, and gentle, tolerable exercise (chair yoga, tai chi, stretching), as well as comorbidity symptom management.

Notable studies

- 2011, Migraine headaches in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS): comparison of two prospective cross-sectional studies.[2]

- 2013, Migraine in gulf war illness and chronic fatigue syndrome: Prevalence, potential mechanisms, and evaluation.[40] (Full Text)

- 2016, Migraines Are Correlated with Higher Levels of Nitrate-, Nitrite-, and Nitric Oxide-Reducing Oral Microbes in the American Gut Project Cohort[41] (Full Text)

News and articles

Learn more

- Migraine treatment - National Health Service

See also

References

- ↑ Petrarca, Kylie (May 12, 2022). "Migraine and ME/CFS". Association of Migraine Disorders. Retrieved November 23, 2025.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Ravindran, Murugan K; Zheng, Yin; Timbol, Christian; Merck, Samantha J; Baraniuk, James N (March 5, 2011). "Migraine headaches in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS): Comparison of two prospective cross-sectional studies". BMC Neurology. 11 (1). doi:10.1186/1471-2377-11-30. ISSN 1471-2377. PMID 21375763.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Migraine". National Health Service. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ↑ "Migraine - Symptoms". National Health Service. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Khan, Johra; Asoom, Lubna Ibrahim Al; Sunni, Ahmad Al; Rafique, Nazish; Latif, Rabia; Saif, Seham Al; Almandil, Noor B.; Almohazey, Dana; AbdulAzeez, Sayed (July 1, 2021). "Genetics, pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment, management, and prevention of migraine". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 139: 111557. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111557. ISSN 0753-3322.

- ↑ Vincent, Maurice; Viktrup, Lars; Nicholson, Robert A.; Ossipov, Michael H.; Vargas, Bert B. (November 3, 2022). "The not so hidden impact of interictal burden in migraine: A narrative review". Frontiers in Neurology. 13. doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.1032103. ISSN 1664-2295. PMC 9669578.

- ↑ Jaimes, Alex; Rodríguez‐Vico, Jaime; Pajares, Olga; Gómez, Andrea; Porta‐Etessam, Jesús (2025-10). "Association Between Interictal Sensory Hypersensitivities and Vestibular Symptoms in Migraine: A Cross‐Sectional Study". Brain and Behavior. 15 (10). doi:10.1002/brb3.70874. ISSN 2162-3279. PMC 12537835. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "1. Migraine - ICHD-3". ichd-3.org. Retrieved November 23, 2025.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (2018). "The International Classification of Headache Disorders". Cephalalgia (3rd ed.). 38 (1): 1–211. doi:10.1177/0333102417738202. ISSN 0333-1024.

- ↑ "What is Complex Migraine? | National Headache Foundation". headaches.org. Retrieved November 23, 2025.

- ↑ Cammarota, Francescantonio; de Icco, Roberto; Goadsby, Peter; Vaghi, Gloria; Corrado, Michael (October 22, 2024). "High-frequency episodic migraine: Time for its recognition as a migraine subtype?". Cephalalgia. 44 (10): 23. doi:10.1177/03331024241291578 – via Sage Journals Home.

Multiple features differentiate subjects with HFEM from low-frequency episodic migraine and from chronic migraine: education, employment rates, quality of life, disability and psychiatric comorbidities load. Some evidence also suggests that HFEM bears a specific profile of activation of cortical and spinal pain-related pathways, possibly related to maladaptive plasticity.

Check|author-link=value (help); Check|author-link2=value (help); Check|author-link3=value (help); Check|author-link4=value (help); Check|author-link5=value (help) - ↑ Rattanawong, Wanakorn; Rapoport, Alan; Srikiatkhachorn, Anan (2022-08). "Neurobiology of migraine progression". Neurobiology of Pain. 12: 100094. doi:10.1016/j.ynpai.2022.100094. ISSN 2452-073X. PMC 9204797. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Goadsby, Peter; Villar-Martinez, Maria (April 15, 2024). "Vestibular migraine: an update". Current Opinion on Neurology. 37 (3): 12. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000001257. PMC 11064914. PMID 38619053.

Vestibular migraine is an underdiagnosed migraine phenotype that shares the pathophysiological mechanisms of migraine, with growing interest in recent years. A thorough anamnesis is essential to increase sensitivity in patients with unknown cause of dizziness and migraine treatment should be considered (see supplemental video-abstract).

- ↑ "Chapter 1, Episode 10: What is Abdominal Migraine? - Association of Migraine Disorders". www.migrainedisorders.org. Retrieved November 23, 2025.

- ↑ Young, W. B; Gangal, K. S; Aponte, R. J; Kaiser, R. S (June 1, 2007). "Migraine with unilateral motor symptoms: a case-control study". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 78 (6): 600–604. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2006.100214. ISSN 0022-3050. PMC 2077953.

- ↑ Turner, PhD, Dana P; Patel, MD, Twinkle (November 11, 2025). "Information-Theoretic Trigger Surprisal and Future Headache Activity". JAMA Network Open. Archived from the original on November 23, 2025. Check

|authorlink=value (help); Check|authorlink2=value (help) - ↑ Marmura, Michael J. (October 5, 2018). "Triggers, Protectors, and Predictors in Episodic Migraine". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 22 (12). doi:10.1007/s11916-018-0734-0. ISSN 1531-3433.

- ↑ "Overlapping Conditions – American ME and CFS Society". ammes.org. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Carruthers, BM; van de Sande, MI; De Meirleir, KL; Klimas, NG; Broderick, G; Mitchell, T; Staines, D; Powles, ACP; Speight, N; Vallings, R; Bateman, L; Bell, DS; Carlo-Stella, N; Chia, J; Darragh, A; Gerken, A; Jo, D; Lewis, DP; Light, AR; Light, KC; Marshall-Gradisnik, S; McLaren-Howard, J; Mena, I; Miwa, K; Murovska, M; Stevens, SR (2012), Myalgic encephalomyelitis: Adult & Paediatric: International Consensus Primer for Medical Practitioners (PDF), ISBN 978-0-9739335-3-6

- ↑ Petrarca, Kylie (May 12, 2022). "Migraine and ME/CFS". Association of Migraine Disorders. Retrieved November 23, 2025.

- ↑ "Trial Report - Fatigue, CFS and migraine: Intersecting the lines through a cross-sectional study in patients with episodic and chronic migraine, 2023, Kumar | Science for ME". www.s4me.info. Retrieved November 23, 2025.

- ↑ Kumar, Hemant; Dhamija, Kamakshi; Duggal, Ashish; Khwaja, Geeta Anjum; Roshan, Sujata (April 20, 2023). "Fatigue, chronic fatigue syndrome and migraine: Intersecting the lines through a cross-sectional study in patients with episodic and chronic migraine". Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice. 14 (3): 424–431. doi:10.25259/JNRP_63_2022. ISSN 0976-3155. PMC 10483198.

- ↑ Huang, Katherine; G. C. de Sá, Alex; Thomas, Natalie; Phair, Robert D.; Gooley, Paul R.; Ascher, David B.; Armstrong, Christopher W. (November 26, 2024). "Discriminating Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and comorbid conditions using metabolomics in UK Biobank". Communications Medicine. 4 (1). doi:10.1038/s43856-024-00669-7. ISSN 2730-664X. PMC 11599898.

- ↑ Nazia, Karsan,; J., Goadsby, Peter (June 3, 2021). "Migraine Is More Than Just Headache: Is the Link to Chronic Fatigue and Mood Disorders Simply Due to Shared Biological Systems?". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 15. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2021.646692/full. ISSN 1662-5161.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- ↑ Fall, Elizabeth A.; Chen, Yang; Lin, Jin-Mann S.; Issa, Anindita; Brimmer, Dana J.; Bateman, Lucinda; Lapp, Charles W.; Podell, Richard N.; Natelson, Benjamin H.; Kogelnik, Andreas M.; Klimas, Nancy G. (October 18, 2024). "Chronic Overlapping Pain Conditions in people with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): a sample from the Multi-site Clinical Assessment of ME/CFS (MCAM) study". BMC Neurology. 24 (1). doi:10.1186/s12883-024-03872-0. ISSN 1471-2377. PMC 11488184.

- ↑ Kim, Joonho; Chu, Min Kyung (June 30, 2025). "Genetic Architecture of Migraine: From Broad Insights to East Asian Perspectives". Headache and Pain Research. 26 (2): 116–129. doi:10.62087/hpr.2025.0003 Check

|doi=value (help). ISSN 3022-9057. - ↑ Bourke, Julius H.; Wodehouse, Theresa; Clark, Lucy V.; Constantinou, Elena; Kidd, Bruce L.; Langford, Richard; Mehta, Vivek; White, Peter D. (2021-11). "Central sensitisation in chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia; a case control study". Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 150: 110624. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110624. ISSN 0022-3999. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Migraine Guide: Causes, Symptoms and Treatment Options". Drugs.com. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Negro, Andrea; Martelletti, Paolo (June 2019). "Gepants for the treatment of migraine". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 28 (6): 555–567. doi:10.1080/13543784.2019.1618830. ISSN 1744-7658. PMID 31081399.

- ↑ Cocores, Alexandra N.; Smirnoff, Liza; Greco, Guy; Herrera, Ricardo; Monteith, Teshamae S. (February 15, 2025). "Update on Neuromodulation for Migraine and Other Primary Headache Disorders: Recent Advances and New Indications". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 29 (1). doi:10.1007/s11916-024-01314-7. ISSN 1531-3433. PMC 11829934.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 "Migraine - Prevention". National Health Service. October 23, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ↑ "Chapter 5, Episode 4: Nerve Blocks for Migraine Disease - Association of Migraine Disorders". www.migrainedisorders.org. Retrieved November 23, 2025.

- ↑ Paudel, Prayash; Sah, Asutosh (2025-06). "Efficacy of biofeedback for migraine: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 90: 103153. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2025.103153. ISSN 0965-2299. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Reyes, Nicholas; Huang, Jaxon J.; Choudhury, Anjalee; Pondelis, Nicholas; Locatelli, Elyana V.T.; Hollinger, Ruby; Felix, Elizabeth R.; Pattany, Pradip M.; Galor, Anat; Moulton, Eric A. (2024-03). "FL-41 Tint Reduces Activation of Neural Pathways of Photophobia in Patients with Chronic Ocular Pain". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 259: 172–184. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2023.12.004. ISSN 0002-9394. PMC 10939838. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Sun-Edelstein, Christina; Mauskop, Alexander (March 2011). "Alternative Headache Treatments: Nutraceuticals, Behavioral and Physical Treatments: March 2011". Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 51 (3): 469–483. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01846.x.

- ↑ Barmherzig, Rebecca; Rajapakse, Thilinie (May 10, 2021). "Nutraceuticals and Behavioral Therapy for Headache". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 21 (7): 33. doi:10.1007/s11910-021-01120-3. ISSN 1534-6293.

- ↑ Sun-Edelstein, Christina; Mauskop, Alexander (June 2009). "Foods and Supplements in the Management of Migraine Headaches". The Clinical Journal of Pain. 25 (5): 446–452. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e31819a6f65. ISSN 0749-8047.

- ↑ "Dietary Supplements for Headaches: What the Science Says". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ↑ Cascio Rizzo, Angelo; Paolucci, Matteo; Altavilla, Riccardo; Brunelli, Nicoletta; Assenza, Federica; Altamura, Claudia; Vernieri, Fabrizio (2017). "Daith Piercing in a Case of Chronic Migraine: A Possible Vagal Modulation". Frontiers in Neurology. 8. doi:10.3389/fneur.2017.00624. ISSN 1664-2295. PMC 5711775. PMID 29230190.

- ↑ Rayhan, Rakib U.; Ravindran, Murugan K.; Baraniuk, James N. (2013). "Migraine in gulf war illness and chronic fatigue syndrome: prevalence, potential mechanisms, and evaluation". Frontiers in Physiology. 4: 181. doi:10.3389/fphys.2013.00181. ISSN 1664-042X. PMID 23898301.

- ↑ Gonzalez, Antonio; Hyde, Embriette; Sangwan, Naseer; Gilbert, Jack A.; Virre, Erik; Knight, Rob (October 18, 2016). "Migraines Are Correlated with Higher Levels of Nitrate-, Nitrite-, and Nitric Oxide-Reducing Oral Microbes in the American Gut Project Cohort" (PDF). American Society for Microbiology. 1 (5).

- ↑ Johnson, Cort (May 19, 2018). "The Migraine Drug Explosion Begins: Could Fibromyalgia and ME/CFS Benefit? - Health Rising". Health Rising. Retrieved August 11, 2018.