International Consensus Criteria

The Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) International Consensus Criteria (ICC)[1] is a medical case definition that can accurately diagnose myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), is a chronic, inflammatory, physically and neurologically disabling disease. For pediatric and adult cases a diagnosis should be made immediately; there is no need to wait up to 6 months.

Authors

Bruce Carruthers, Marjorie van de Sande, Kenny de Meirleir, Nancy Klimas, Gordon Broderick, Terry Mitchell, Donald Staines, A C Peter Powles, Nigel Speight, Rosamund Vallings, Lucinda Bateman, Barbara Baumgarten-Austrheim, David Bell, Nicoletta Carlo-Stella, John Chia, Austin Darragh, Daehyun Jo, Donald Lewis, Alan Light, Sonya Marshall-Gradisnik, Ismael Mena, Judy Mikovits, Kunihisa Miwa, Modra Murovska, Martin Pall, and Staci Stevens[1]

Criteria

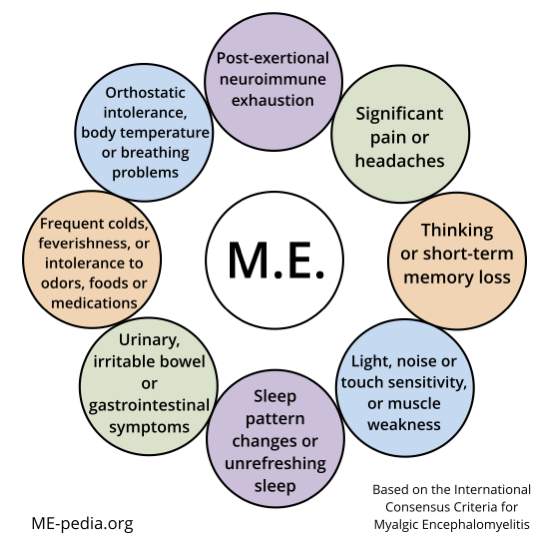

A patient will meet the criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis if they have:

A - Postexertional neuroimmune exhaustion

B - at least ONE neurological impairment symptom from THREE categories:

- Neurocognitive Impairments

- Pain

- Sleep Disturbance

- Neurosensory, Perceptual and Motor Disturbances

C - at least ONE immune/gastro-intestinal/genitourinary impairment from THREE categories:

- Flu-like symptoms may be recurrent or chronic and typically activate or worsen with exertion

- Susceptibility to viral infections with prolonged recovery periods

- Gastro-intestinal tract disturbances

- Genitourinary disturbances

- Sensitivities to food, medications, odors or chemicals, and

D - at least ONE energy metabolism/ion transport impairment symptom.

Postexertional neuroimmune exhaustion (PENE pen’-e): Compulsory | |

| A. |

This cardinal feature is a pathological inability to produce sufficient energy on demand with prominent symptoms primarily in the neuroimmune regions. Characteristics are as follows:

Operational notes: For a diagnosis of ME, symptom severity must result in a significant reduction of a patient's premorbid activity level. Mild (an approximate 50% reduction in pre-illness activity level), moderate (mostly housebound), severe (mostly bedridden) or very severe (totally bedridden and need help with basic functions). There may be marked fluctuation of symptom severity and hierarchy from day to day or hour to hour. Consider activity, context and interactive effects. Recovery time: e.g. Regardless of a patient’s recovery time from reading for ½ hour, it will take much longer to recover from grocery shopping for ½ hour and even longer if repeated the next day – if able. Those who rest before an activity or have adjusted their activity level to their limited energy may have shorter recovery periods than those who do not pace their activities adequately. Impact: e.g. An outstanding athlete could have a 50% reduction in his/her pre-illness activity level and is still more active than a sedentary person. |

Neurological impairments | |

| B. |

At least one symptom from three of the following four symptom categories 1. Neurocognitive impairments

2. Pain

3. Sleep disturbance

4. Neurosensory, perceptual and motor disturbances

Notes: Neurocognitive impairments, reported or observed, become more pronounced with fatigue. Overload phenomena may be evident when two tasks are performed simultaneously. Abnormal accommodation responses of the pupils are common. Sleep disturbances are typically expressed by prolonged sleep, sometimes extreme, in the acute phase and often evolve into marked sleep reversal in the chronic stage. Motor disturbances may not be evident in mild or moderate cases but abnormal tandem gait and positive Romberg test may be observed in severe cases. |

Immune, gastro-intestinal and genitourinary impairments | |

| C. |

At least one symptom from three of the following five symptom categories

Notes: Sore throat, tender lymph nodes, and flu-like symptoms obviously are not specific to ME but their activation in reaction to exertion is abnormal. The throat may feel sore, dry and scratchy. Faucial injection and crimson crescents may be seen in the tonsillar fossae, which are an indication of immune activation. |

Energy production/transportation impairments: At least one symptom | |

| D. |

Notes: Orthostatic intolerance may be delayed by several minutes. Patients who have orthostatic intolerance may exhibit mottling of extremities, extreme pallor or Raynaud's Phenomenon. In the chronic phase, moons of finger nails may recede. |

Paediatric considerations | |

Symptoms may progress more slowly in children than in teenagers or adults. In addition to postexertional neuroimmune exhaustion, the most prominent symptoms tend to be neurological: headaches, cognitive impairments, and sleep disturbances.

Notes: Fluctuation and severity hierarchy of numerous prominent symptoms tend to vary more rapidly and dramatically. | |

Classification——— Myalgic encephalomyelitis ——— Atypical myalgic encephalomyelitis: | |

Exclusions | |

| As in all diagnoses, exclusion of alternate explanatory diagnoses is achieved by the patient’s history, physical examination, and laboratory/biomarker testing as indicated. It is possible to have more than one disease but it is important that each one is identified and treated. Primary psychiatric disorders, somatoform disorder and substance abuse are excluded. Paediatric: 'primary' school phobia. | |

Comorbid entities | |

| Fibromyalgia, myofascial pain syndrome, temporomandibular joint syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, prolapsed mitral valve, migraines, allergies, multiple chemical sensitivities, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, Sicca syndrome, reactive depression. Migraine and irritable bowel syndrome may precede ME but then become associated with it. Fibromyalgia overlaps. | |

Background and purpose

The 2012 ICC is very clear on the topic of names:

Problem

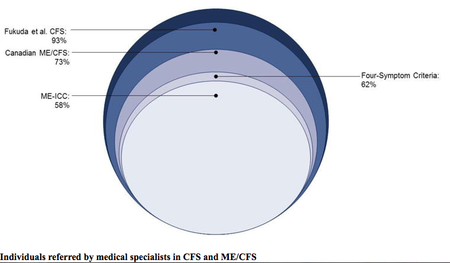

The label ‘chronic fatigue syndrome’ (CFS), coined in the 1980s, has persisted due to lack of knowledge of its etiologic agents and pathophysiology. Misperceptions have arisen because the name ‘CFS’ and its hybrids ME/CFS, CFS/ME and CFS/CF have been used for widely diverse conditions. Patient sets can include those who are seriously ill with ME, many bedridden and unable to care for themselves, to those who have general fatigue or, under the Reeves criteria, patients are not required to have any physical symptoms. There is a poignant need to untangle the web of confusion caused by mixing diverse and often overly inclusive patient populations in one heterogeneous, multi-rubric pot called ‘chronic fatigue syndrome’. We believe this is the foremost cause of diluted and inconsistent research findings, which hinders progress, fosters scepticism, and wastes limited research monies.

Solution

The rationale for the development of the ICC was to utilize current research knowledge to identify objective, measurable and reproducible abnormalities that directly reflect the interactive, regulatory components of the underlying pathophysiology of ME. Specifically, the ICC select patients who exhibit explicit multi-systemic neuropathology, and have a pathological low threshold of physical and mental fatigability in response to exertion. Cardiopulmonary exercise test- retest studies have confirmed many post-exertional abnormalities. Criterial symptoms are compulsory and identify patients who have greater physical, cognitive and functional impairments. The ICC advance the successful strategy of the Canadian Consensus Criteria (CCC) of grouping coordinated patterns of symptom clusters that identify areas of pathology. The criteria are designed for both clinical and research settings.

1. Name: Myalgic encephalomyelitis, a name that originated in the 1950s, is the most accurate and appropriate name because it reflects the underlying multi-system pathophysiology of the disease. Our panel strongly recommends that only the name ‘myalgic encephalomyelitis’ be used to identify patients meeting the ICC because a distinctive disease entity should have one name. Patients diagnosed using broader or other criteria for CFS or its hybrids (Oxford, Reeves, London, Fukuda, CCC, etc.) should be reassessed with the ICC. Those who fulfill the criteria have ME; those who do not would remain in the more encompassing CFS classification. (bold emphasis mine)

2. Remove patients who satisfy the ICC from the broader category of CFS. The purpose of diagnosis is to provide clarity. The criterial symptoms, such as the distinctive abnormal responses to exertion can differentiate ME patients from those who are depressed or have other fatiguing conditions. Not only is it common sense to extricate ME patients from the assortment of conditions assembled under the CFS umbrella, it is compliant with the WHO classification rule that a disease cannot be classified under more than one rubric. The panel is not dismissing the broad components of fatiguing illnesses, but rather the ICC are a refinement of patient stratification. As other identifiable patient sets are identified and supported by research, they would then be removed from the broad CFS/CF category.

Research on ME: The logical way to advance science is to select a relatively homogeneous patient set that can be studied to identify biopathological mechanisms, biomarkers and disease process specific to that patient set, as well as comparing it to other patient sets. It is counterproductive to use inconsistent and overly inclusive criteria to glean insight into the pathophysiology of ME if up to 90% of the research patient sets may not meet its criteria (Jason 2009). Research on other fatiguing illnesses, such as cancer and multiple sclerosis (MS), is done on patients who have those diseases. There is a current, urgent need for ME research using patients who actually have ME. (bold emphasis mine)

4. Research confirmation: When research is applied to patients satisfying the ICC, previous findings based on broader criteria will be confirmed or refuted. Validation of ME being a differential diagnosis, as is multiple sclerosis (MS), or a subgroup of chronic fatigue syndrome, will then be verified.

5. Focus on treatment efficacy: With enhanced understanding of biopathological mechanisms, biomarkers and other components of pathophysiology specific to ME, more focus and research emphasis can target expanding and augmenting treatment efficacy.

International Consensus Primer (ICP)

Problem

Overly inclusive criteria have created misperceptions, fostered cynicism and have had a major negative impact on how ME is viewed by the medical community, patients, their families, as well as the general public. Some medical schools do not include ME in their curriculum with the result that very significant scientific advances and appropriate diagnostic and treatment protocols have not reached many busy medical practitioners. Some doctors may be unaware of the complexity and serious nature of ME. Patients may go undiagnosed and untreated; they may be shunned or isolated.[2]

World Health Organisation

The World Health Organisation (WHO) lists ME and post viral fatigue syndrome under neurological conditions. The diagnostic code is G93.3[3] Importantly, it doesn’t include chronic fatigue syndrome there, or ME/CFS or CFS/ME. Fatigue syndromes are listed in "Other neurotic disorders."[4]

Comparison with other criteria

- Norwegian researchers compare the main criteria (Oxford criteria, Fukuda criteria, Canadian Consensus Criteria, International Consensus Criteria and SEID). They say "it is important to distinguish between myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome” to improve understanding of the disease, treatment and patients’ lives, as using incorrect criteria can lead to incorrect treatment.[5]

- 'Scientists must agree on classifying patients’ Leonard Jason[6]

- Frank Twisk explains that ME and CFS are "distinct, partially overlapping, clinical entities such as ME and CFS" Frank Twisk 2016[7]

Diagram of ME ICC symptoms

Tool to determine if you meet ICC criteria

The following online questionnaire was developed by Schweizerische Gesellschaft für ME & CFS, a patient association in Switzerland, to help you determine whether the diagnosis of ME (Myalgic Encephalomyelitis) according to the International Consensus Criteria (ICC) is applicable to you. English and Dutch versions are available.[8]

See also

- Definitions of ME and CFS

- Canadian Consensus Criteria

- List of symptoms in ME/CFS

- Common symptoms

- Differential diagnosis

Generally accepted criteria for diagnosing ME and ME/CFS

- Canadian Consensus Criteria (CCC)[9] A diagnosis of moderate and severe forms of ME/CFS are accurately made using this criterion. Adults can be diagnosed at 6 months while pediatric cases are diagnosed at three months.

- International Consensus Criteria (ICC)[1] This criterion will accurately diagnose myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME). There is no requirement that the individual have symptoms for a specified period of time for diagnosis, as opposed to CCC, Fukuda, and SEID, which all require 6 months in adults.

- Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease (SEID)[10] ME/CFS (SEID) is accurately diagnosed when the core symptoms are met. The Institute of Medicine report as a whole is a comprehensive review of the medical literature available at time of publication (2015). Adults can be diagnosed at 6 months while pediatric cases are diagnosed at three months.

Learn more

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Carruthers, Bruce M.; van de Sande, Marjorie I.; De Meirleir, Kenny L.; Klimas, Nancy G.; Broderick, Gordon; Mitchell, Terry; Staines, Donald; Powles, A.C. Peter; Speight, Nigel; Vallings, Rosamund; Bateman, Lucinda; Baumgarten-Austrheim, Barbara; Bell, David; Carlo-Stella, Nicoletta; Chia, John; Darragh, Austin; Jo, Daehyun; Lewis, Donald; Light, Alan; Marshall-Gradisnik, Sonya; Mena, Ismael; Mikovits, Judy; Miwa, Kunihisa; Murovska, Modra; Pall, Martin; Stevens, Staci (August 22, 2011). "Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria". Journal of Internal Medicine. 270 (4): 327–338. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02428.x. ISSN 0954-6820. PMC 3427890. PMID 21777306.

- ↑ Carruthers, BM; van de Sande, MI; De Meirleir, KL; Klimas, NG; Broderick, G; Mitchell, T; Staines, D; Powles, ACP; Speight, N; Vallings, R; Bateman, L; Bell, DS; Carlo-Stella, N; Chia, J; Darragh, A; Gerken, A; Jo, D; Lewis, DP; Light, AR; Light, KC; Marshall-Gradisnik, S; McLaren-Howard, J; Mena, I; Miwa, K; Murovska, M; Stevens, SR (2012), Myalgic encephalomyelitis: Adult & Paediatric: International Consensus Primer for Medical Practitioners (PDF), ISBN 978-0-9739335-3-6

- ↑ WHO Classifications G93.3 - 2016

- ↑ WHO Classifications F48.0 - 2016

- ↑ Egeland, T; Angelsen, A; Haug, R; Henriksen, JO; Lea, TE; Saugstad, OD (October 2015), "What exactly is myalgic encephalomyelitis?", Tidsskr Nor Legeforen (Perspectives), 2015 (135): 1756–9, doi:10.4045/tidsskr.15.0089, lay summary

- ↑ Jason, Leonard A.; McManimen, Stephanie; Sunnquist, Madison; Brown, Abigail; Furst, Jacob; Newton, Julia L.; Strand, Elin Bolle (January 2, 2016). "Case definitions integrating empiric and consensus perspectives". Fatigue: Biomedicine, Health & Behavior. 4 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1080/21641846.2015.1124520. ISSN 2164-1846. PMC 4831204. PMID 27088059.

- ↑ Twisk, Frank NM (June 26, 2015). "Accurate diagnosis of myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome based upon objective test methods for characteristic symptoms". World Journal of Methodology. 5 (2): 68–87. doi:10.5662/wjm.v5.i2.68. ISSN 2222-0682. PMC 4482824. PMID 26140274.

- ↑ "Do I Have ME?". Retrieved January 10, 2022.

- ↑ Carruthers, Bruce M.; Jain, Anil Kumar; De Meirleir, Kenny L.; Peterson, Daniel L.; Klimas, Nancy G.; Lerner, A. Martin; Bested, Alison C.; Flor-Henry, Pierre; Joshi, Pradip; Powles, AC Peter; Sherkey, Jeffrey A.; van de Sande, Marjorie I. (2003), "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Clinical Working Case Definition, Diagnostic and Treatment Protocols" (PDF), Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, 11 (2): 7–115, doi:10.1300/J092v11n01_02

- ↑ Clayton, Ellen Wright; Alegria, Margarita; Bateman, Lucinda; Chu, Lily; Cleeland, Charles; Davis, Ronald; Diamond, Betty; Ganiats, Theodore; Keller, Betsy; Klimas, Nancy; Lerner, A Martin; Mulrow, Cynthia; Natelson, Benjamin; Rowe, Peter; Shelanski, Michael (2015). "Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome - Redefining an Illness" (PDF). National Academies.