Multiple chemical sensitivity

Multiple chemical sensitivity (MCS), also known as idiopathic environmental intolerances (IEI), is an acquired, chronic, multi-system illness, in which people experience a range of symptoms in response to exposure to certain everyday chemicals.

A 2018 scientific review said MCS was "a complex syndrome that manifests as a result of exposure to a low level of various common contaminants."[1]

While a 2019 consensus paper on MCS defined the condition as an "acquired disorder, characterized by recurrent symptoms, affecting multiple organs and systems, which arise in response to a demonstrable exposure to chemicals," even at doses much lower than would cause a reaction in the general population.[2]

Common triggers for MCS symptoms include pesticides, fragranced products, petrochemicals, formaldehyde and mold.[3][4]

Signs and symptoms

There is a consensus that the symptoms of MCS affect multiple organs and body systems,[3][5][6] that symptoms range from mild to severely disabling,[3][7][8] and decrease quality of life.[6][9][8][10][11][12][13][14][15]

Symptoms of MCS can include headache, migraine, neurocognitive deficits, dizziness, fatigue, cardiac arrhythmia, tachycardia, hypotension, hypertension (high blood pressure), gastrointestinal problems, nausea, vomiting, muscle and joint pain, skin rashes, hives, visual disturbances, seizures, and asthma.[3][7][16][8][9][17][18][19] And a 2010 review of MCS research said that the following symptoms, in this order, were the most reported in MCS: headache, fatigue, confusion, depression, shortness of breath, arthralgia, myalgia, nausea, dizziness, memory problems, gastrointestinal symptoms, respiratory symptoms.[7]

A 2017 review of MCS studies said: “MCS is a syndrome that progresses to increasingly serious stages, with the gradual onset of multiple pathologies."[1] It can be associated with very high levels of disability.

Chemicals that trigger symptoms

The following substances are common triggers for adverse symptoms in people with MCS:

- pesticides (insecticides and herbicides), biocides and fungicides

- agricultural chemicals, notably fertilizers

- mold and mycotoxins

- synthetic fragrances and products containing fragrance (e.g. fragranced deodorant)

- laundry detergents and fabric softeners

- cigarette smoke and woodfire smoke

- petrochemical solvents and plastics

- formaldehyde

- some building materials

- preservatives, food colorings and additives (e.g. tartrazine)

- some medications and anesthetics

- air pollution (e.g. black carbon, nitrogen oxide, ozone)

- natural essential oils.[1][3][7][5][9][22][16]:17[23][24]

Diagnosis and diagnostic criteria

Research papers have concluded that knowledge and education about MCS among health professionals is lacking and that this commonly results in delays in the diagnosis and poor management of the condition.[14][7][8]

International Consensus Criteria 1999

The 1999 international consensus on MCS is the most commonly used diagnostic criteria for MCS. The consensus is based on the Cullen criteria plus a ten-year study by an international multidisciplinary team of 89 clinicians and researchers with different points of view about MCS.[3][5] MCS is defined as:

- a chronic condition,

- with symptoms that recur reproducibly

- in response to low levels of exposure

- to multiple and unrelated chemicals,

- which improve or resolve when triggers are removed, and

- with symptoms which occur in multiple organ systems.[5][3][25]

Lacour criteria 2005

- symptom duration of at least 6 months

- symptoms in response to at least 2 of 11 categories of chemical exposures

- at least one central nervous system symptom is present (eg fatigue, headaches or neurocognitive deficits, and one symptom from another organ system

- symptoms causing adjustments of personal lifestyle, or of social or occupational life

- symptoms occurring when exposed and improving or resolving when exposures are removed

- symptoms are triggered by exposure levels that do not induce symptoms in other individuals who are exposed to the same levels[26][27][28]

Diagnostic tools

The Quick Environmental Exposure and Sensitivity Inventory (QEESI) is a diagnostic tool that is often used to assess a patient for these criteria.[3]

Differential diagnosis

A series of tests are needed to identify other potential causes of the symptoms. Particularly important to rule out are:

- Porphyrias

- Mastocytosis including systematic mastocytosis[28]

Prevalence

While prevalence rates for MCS vary according to the diagnostic criteria used,[2][7] the condition is reported across industrialized countries and the data suggests it affects women more than men.[8]:37[29][30][31][32][16]:2,39[33][1]

The most extensive epidemiological study into MCS in the U.S. was in 2005.[2] It found that the national prevalence rate for MCS diagnosed by a doctor was 2.5% and self-reported MCS was 11.2%.[2][34][35]

In 2018, the same researchers reported that the prevalence rate of diagnosed MCS had increased by more than 300% and self-reported chemical sensitivity by more than 200% in the previous decade. They found that 12.8% of those surveyed reported medically diagnosed MCS and 25.9% reported having chemical sensitivities.[9]

In Denmark, the Ministry of the Environment estimated in 2004 that 10% of the population was sensitive to certain everyday chemicals and that 1% of the population had MCS to a level that was disabling.[36][37]

A 2014 study by the Canadian Ministry of Health estimated, based on its survey, that 0.9% of Canadian males and 3.3% of Canadian females had a diagnosis of MCS by a health professional.[8]:37[38]

While a 2018 study at the University of Melbourne found that 1 million Australians (6.5% of adults) reported having a medical diagnosis of MCS and that 18.9% reported having adverse reactions to multiple chemicals.[2][24][39] The study also found that for 55.4% of those with MCS, the symptoms triggered by chemical exposures could be disabling.[9][39]

Recognition

In 1996, an expert panel at WHO/ICPS (International Classification for Patient Safety) was set up to examine MCS.[40] The panel:

- "accepted the existence of a disease of unclear pathogenesis",

- proposed that the disease was acquired, that its symptoms were "in close relationship to multiple environmental influences, which are well tolerated by the majority of the population," and that it "could not be explained by a known clinical or psychic disorder,"

- suggested that the broader term "idiopathic environmental intolerances" (IEI) be adopted instead of MCS, to incorporate MCS and several other conditions under a single umbrella term.[40]

MCS is not included as a separate, discrete disease by the World Health Organization's (WHO) index of diseases (ICD-11). However, existing disease codes in the ICD-10 can be used for MCS, including:

- J68.9: unspecified respiratory conditions due to inhalation of fumes, gas, and chemical vapors; and

- T78.4: unspecified allergies (allergic reaction Nitrous Oxide System (NOS)-hypersensitivity NOS-idiosyncrasy NOS)."[1]:139

In the ICD-10-DM and ICD-10-SGB-V, Germany's adaptions of the ICD-10, multiple chemical sensitivity is recognized as a chemical hypersensitivity or intolerance (Chemical-Sensitivity[MCS]-Syndrom, Multiple-) under the code T78.4; this is also in use in Austria.[41][1] Japan also recognizes MCS as a separate disease.[1]:139[42][7] And in some countries, like Sweden, chemical sensitivities are classified as a form of sensory hyperreactivity (CSS-SHR).[9] In 2012, Denmark introduced code DR688A1 for Symptoms related to chemicals and scents (Symptomer relateret til dufte og kemiske stoffer fra SKS), in the Medically Unexplained Symptoms, under R68.8 Other specified general symptoms and signs.[37]

And as mentioned above, chemical sensitivities are recognized symptoms of ME/CFS. In 2018, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said that ME/CFS patients can have sensitivities to chemicals.[43]

Treatment

There is no clinically proven cure for MCS.[8][42] There is also no scientific consensus on supportive therapies, "but the literature agrees on the need for patients with MCS to avoid the specific substances that trigger reactions for them and also on the avoidance of xenobiotics in general, to prevent further sensitization."[7][8][16][23][42]

A study, which surveyed more than 900 people with MCS about their experiences managing the condition, found that 95% of respondents thought that "creating a chemical-free living space and chemical avoidance" had been the best strategy out of any management or treatment option they had tried.[7][46]

There is also consensus that a multidisciplinary approach is required for adequately managing the health of someone with MCS.[6][42]

There is evidence that some patients with MCS might have poor tissue oxygenation when exposed to triggers,[45] perhaps because of oxidative stress or because neural inflammation has reduced blood flow.[45][47][48][49] Breathing medical oxygen following accidental chemical exposures helps some people.[45] The 2019 consensus and clinical guidelines on MCS said that people with MCS "must be guaranteed, according to their individual needs and level of disability" medical oxygen and the necessary equipment to use it (that is, tubing and a mask from non-triggering materials).[44]

The other aids the 2019 consensus said were necessary for patients with MCS to manage the functional impacts of their condition were:

- face masks (with HEPA and VOC filters)

- portable air purifiers for the home and for inside vehicles (made of metal, with HEPA and activated carbon filters), and

- water purifiers.[44]

Accessibility needs

People with MCS typically experience significant access barriers to society and accessing services. They are also commonly subject to stigma and lack of understanding, perhaps because the condition is poorly understood. Nevertheless, it is recognised as a disability. For example, "a growing number of people report being affected by sensitivity to chemicals used in the building, maintenance and operation of premises," according to the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. "This can mean that premises are effectively inaccessible to people with chemical sensitivity.”[50]

Various organisations and workplaces have policies which cite chemical or fragrance sensitivities as a disability access or occupational health and safety issue.[8][20][51][39][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62] The most influential of these may be the indoor air quality policy of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which says:

- "Scented or fragranced products are prohibited at all times in all interior space owned, rented, or leased by CDC;"[21]

- "CDC encourages employees to be as fragrance-free as possible when they arrive in the workplace...Employees should avoid using scented detergents and fabric softeners on clothes worn to the office. Many fragrance-free personal care and laundry products are easily available and provide safer alternatives;" and

- "Fragrance is not appropriate for a professional work environment, and the use of some products with fragrance may be detrimental to the health of workers with chemical sensitivities, allergies, asthma, and chronic headaches/migraines."[21]

Common ingredients in synthetic fragrance are recognized as irritants for a range of respiratory conditions.[63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75] The American Lung Association lists fragrance on their list of "indoor air pollutants" and recommends that healthy workplaces establish fragrance-free policies for employees and visitors."[20]:30 With this in mind, some have called for fragrance-free policies in hospitals and healthcare settings.

There is anecdotal evidence of people with MCS facing significantly higher levels of disability as a direct result of certain Covid-19 policies. This is said to be "due to greater exposure to disinfectants and fragranced products as well as increased barriers to essential needs such as food and healthcare."[76]

Hospital care

Hospitals with fragrance-free policies are common in Canada and Sweden.[39][20][8][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62] Canadian examples include:

- Mount Sinai Hospital has a fragrance-free policy, which says the hospital "is committed to providing a safe and inclusive environment for all and will strive to eliminate the use of products with scents and fragrances to prevent any adverse reactions in patients, staff and other people working and/or visiting the hospital premises."[53]

- Kingston General Hospital is fragrance free "for the safety and comfort of those with allergies and sensitivities," and its web site says "other items that you should not use or bring when you visit the hospital include: perfumes and colognes, scented fabric softeners, stain removers and laundry detergents, scented soaps and deodorant, scented shampoos and hair products, scented body powders and lotions."[54]

As well as fragrance-free policies, to prevent adverse reactions and improve health outcomes in hospital settings, patients with MCS often require adjustments in chemical use, medications and anesthetics.[77][78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86]

Some states and regions have specific policies for the hospital care of patients with MCS. For example, in Australia, three states and a territory have detailed hospital policies for patients with MCS.[82][81][86][85] As well, some individual hospitals have their own policies for MCS patients.[78][87]

Housing

People with MCS commonly encounter difficulties finding housing that is suitable and accessible for their condition; and as a result, homelessness is a systemic problem for those with the condition.[88][89][90][91][92][93]:12

A 2002 housing survey of people with MCS in the United States found that:

- 57% of respondents had experienced homelessness during their illness (compared to 1% of the general population reporting having experienced homeless in their lifetime)

- 25% had lived in a car (nine months average)

- 15% had lived in a tent (eight months average)

- 73% of respondents had lived in a house that made them sick

- 47% said they were spending more than they could afford on accessible housing

- 43% said their current housing was neither accessible nor permanent.[89]

While a 2019 survey in Australia found that 55.2% of respondents with chemical sensitivities reported suffering hardship accessing safe and affordable housing.[90]

A 2016 academic review about the psychosocial impacts of environmental sensitivities found that “as persons acquire sensitivities, it becomes more and more difficult [for them] to find or maintain housing that does not exacerbate the condition." It also said two-thirds of people with environmental sensitivities had reported having had to live in "unusual circumstances" as a result of their condition at some period of their illness.[91]

A 2019 report from Canada about human rights' issues faced by people with environmental illness said: “In focus groups, participants with environmental health disabilities voiced significant concerns about the barriers they experience in finding and maintaining accessible and affordable rental housing".[92] Some of these included:

- mold

- carpet

- fumes from paint

- pesticide residue

- fumes from [nearby] laundry facilities

- fumes from cleaning products in common areas and

- cigarette smoke.[92]

People with MCS suffer as a result of their lack of access to safe housing, according to a 2018 government inquiry from Ontario, Canada.[93] The inquiry concluded that in society at large, there was little recognition of how serious and severe environmental illness could be and that there was "a discouraging shortage of services and supports" for people living with conditions like MCS.[93] It also found that people with environmental illness commonly experienced stigma, including from landlords, who were "often skeptical about the severity and impact of their conditions.”[93]:7,12,19

History

In 1956, American allergist Dr. Theron G. Randolph coined the term "environmental illness," to describe symptoms and disorders he observed in some of his patients after they were exposed to various unrelated chemical compounds.[7][40]

Then in 1987, Dr. Mark R. Cullen, also an American allergist, introduced the term MCS in journals of occupational medicine. He proposed that MCS described: an acquired disorder, characterized by recurrent symptoms, affecting multiple organs and systems, which arose in response to a demonstrable exposure to chemicals, even for low doses, much lower than those causing reactions in the general population.[7][40]

Two years later, an international multidisciplinary team of 89 clinicians and researchers commenced a study into MCS, which culminated in the first real international consensus on the condition being agreed upon and published in The Archives of Environmental Health in 1999.[1][5]

In 1996, an expert panel of the World Health Organization/International Classification for Patient Safety (WHO/ICPS) accepted the existence of MCS as a health condition with a cause unknown, and suggested that it be called "idiopathic environmental intolerances"(IEI), a term that incorporates a number of conditions sharing similar symptoms.[40]

In May 2019, the Italian Workgroup on MCS, a group of physicians, research scientists and clinical staff, published a detailed, 30-page consensus paper called the Italian Consensus on MCS.[94] This document may be the most detailed scientific review of research about MCS to date. It goes into detail about ways the condition can be better managed in clinical environments, particularly in hospitals. The workgroup published their consensus in Italian and English, asking for input from MDs and other health professionals, biologists and chemists. At the time of writing, the response to the consensus had not been published.

Possible causes

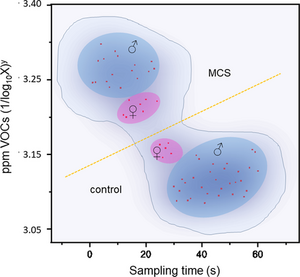

Basal exhaled VOCs data for MCS and controls, acquired with the ORT-VOC, are shown in a density plot.

Source: Mazzatenta et al. (2021). Physiological Reports, 9, e15034.[95]

In 2017, a Canadian government Task Force on Environmental Health said that there had been very little rigorous peer-reviewed research into MCS and almost a complete lack of funding for such research in North America.[8]:53 "Most recently," it said, "some peer-reviewed clinical research has emerged from centres in Italy, Denmark and Japan suggesting that there are fundamental neurobiologic, metabolic, and genetic susceptibility factors that underlie ES (Environmental Sensitivities)/MCS."[8]:53

The Italian consensus on MCS of 2019 said that the current consensus for the cause of MCS is that it likely has multiple causes: biochemical, neuro-physiological, causes related to the limbic system and perhaps also genetic predisposition.[96]

When speaking at an Australian federal parliamentary inquiry into environmental illness, in 2018, Dr Graeme Edwards, the inquiry's representative of Royal Australasian College of Physicians[97] said that there was "relatively good consensus" that causation was multifactorial. "There is no single causative factor," he said. "It is a combination of factors ... unless you have all the pieces of the puzzle lining up, you actually don't get the disease. And because we are talking about multi-dimensional triggers, any one individual, at any one point in time, may not have exposure to all of those triggers to get a pathological result. And therein lies the complexity."[98]:11

These recent statements suggest that earlier depictions of MCS as being either biologically or psychologically caused likely set up a false dichotomy or divide.

In 2021, a small study by Mazzatenta and colleagues found breath analysis of key volatile organic compounds (VOCs) differed between MCS patients and healthy controls, raising the possibility that breath analysis may be able to diagnose MCS in future. Breath analysis can already be used to aid diagnosis for some illnesses.[95]

Toxicological

It has been hypothesized that MCS is caused by exposure to particular chemicals—most commonly certain pesticides.

The Toxicant-Induced Loss of Tolerance (TILT) hypothesis proposed by Miller (1996) uses the name TILT for multiple chemical sensitivity, and describes a two-phase process. First, there is either a single major exposure to chemicals or many smaller exposures, which then result in chemical intolerance or sensitization. In the second phase, low or very low levels of exposure to chemicals cause symptoms that did not occur before sensitization.[99] According to the TILT hypothesis, food and medication intolerances frequently occur along with chemical sensitivity. Miller (2021) believes that Mast Cell Activation Syndrome may account for TILT/MCS.[100]

Professor Martin L. Pall proposed that MCS had a toxicological and biochemical cause, and that "seven individual chemicals or chemical classes—organophosphorus/carbamate, organochloride and pyrethroid pesticides, organic solvents, carbon monoxide, hydrogen sulphide and mercury/mercurial compounds—could initiate MCS through their ability to increase N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor activity."[4][7]

Pall hypothesized that overactivity of the NMDA receptors, coupled with stress-related increases in nitric oxide and the oxidative product peroxynitrite (known as the NO/ONOO cycle) caused MCS symptoms and worsened the condition.[22][101] He suggested that hypersensitivity occurred because of limbic kindling, neural sensitization, and/or neurogenic inflammation—processes which could be driven by the NO/ONOO cycle.[7]

A 2019 scientific review said that while further research was required to confirm Pall's theory, his hypothesis "had found broad consensus in the scientific community” and was compatible with previous hypotheses,[96] including Dr. Iris Bell's theory of neuronal sensitization[102][103] and William Meggs' theory of neurogenic inflammation.[104]

It also said that Pall's theory may explain the comorbidity of MCS and other pathologies hypothesized to be related to the same mechanism, including fibromyalgia (FM) and ME/CFS, and that it might be why MCS symptoms tend to lessen after exposure to inhibitors and/or antagonists of NMDA receptors.[96]The review also said that "pesticides, including herbicides, insecticides and agricultural chemicals, are among the substances most commonly implicated in the activation of MCS cases in the United States."[105]

Pall's theory has also been used to explain why Gulf War veterans, particularly those who were exposed to organophosphate pesticides, have been found to be more likely to have MCS than the general population[106][22] as well as the fact that chemical sensitivities are a known symptom reported in Gulf war syndrome or post-deployment syndrome.[107][108][109]

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs concluded that "risk factors that may be associated with predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating chronic multi system illnesses [including MCS] among veterans" included chemical exposure, and notably chemical exposure in the Gulf War, where some military personel were exposed to nerve agents (like sarin and cyclosarine) and toxic smoke.[108]

Mold and mycotoxin exposures have also been hypothesized to trigger the onset of MCS.[110][111][112][98] Exposure to mold has already been associated with initiating inflammation and higher incidences of certain chronic conditions (like asthma), which are common symptoms of MCS.[113][97][114][115][116]

Neurological

Many common symptoms of MCS are neurological[1][6][3] (for example, "dizziness, seizures, head pain, fainting, loss of coordination"[9]). And neurogenic inflammation and a central sensitization syndrome have been thought to be mechanisms involved in causing, perpetuating and worsening MCS.[3][102][103][104][27]

William Meggs said that neurogenic inflammation was a well-defined pathophysiological process, in which chemical irritants triggered nerve fibers to release inflammatory mediators, which led to disease. In a 2017 review, he said that with MCS, an initiating chemical exposure (commonly a respiratory irritant or pesticide) was usually identified in association with the onset of the disease.[104]

Iris Bell researched brain-wave patterns in people with MCS. He showed, in several studies using Electroencephalography (EEG), that people with MCS often had certain abnormal brain wave patterns.[96][117] For example, he found that women with MCS were more likely to have greater resting alpha waves than controls, which he said suggested the possibility of central nervous system hypo-activation.[118]

Multiple neuro-imaging studies have shown that people with MCS often have other neurological abnormalities, including abnormal cerebral perfusion patterns, especially in the autonomic nervous system areas.[96][119][120][121][122][123] These abnormalities have been documented both in studies using Positron emission tomography (PET) and Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scans.[96][124][125]

In addition to people with MCS having documented neurological abnormalities, neuroplasticity is thought by some researchers to be an important mechanism in the disease. In 2018, a representative of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians said: “It could be a multiple chemical sensitivity phenomenon. It could be an irritable bowel phenomenon. It could be fibromyalgia... The common unifying features in all of these conditions is related to what we do know is happening, which is neuroplasticity in the nervous system. We know that, regardless of the initiating trigger—whether it was an overwhelming infection of a mould related organism or some other viral infection—it sets up, within the biological system called the nervous system, neuroplastic changes. They can be, and have been, documented by evidence based research. We can document that there are changes in the nervous system, and that change in the nervous system results in a change in the sensitivity and responsiveness of the human being.”[98]:12[97]

Immunological

MCS is not an allergy, and subjects with MCS having adverse reactions do not routinely exhibit the immune markers associated with allergies.[7]:21 Nevertheless, certain immune irregularities have been identified in subjects with MCS in a range of studies.[1][96][7]:22

In the 1980s and 1990s, some researchers hypothesized that these immune irregularities suggested that MCS was caused by a chemically induced disturbance of the immune system, which resulted in chronic immune dysfunction.[7]:22[17] While others concluded that allergic or immunotoxicological reactions could be contributing factors in at least a subset of MCS patients.[7]:22[126][127] As more studies were conducted, however, some argued that there was no consistent pattern of immunological reactivity or abnormality in MCS.[7]:22[19][128]

More recently, a French study found that subjects with MCS had higher levels of histamine than controls.[96][129] It also identified damage to the blood-brain barrier in MCS subjects, the production of antibodies against myelin and evidence of inflammatory processes involving the limbic system and thalamus. These findings led the research team to conclude that some level of immune activation was likely occurring in the condition.[96][129]

There is also evidence that subjects with MCS are more likely than controls to have real allergies[16]:16 and autoimmune diseases. And the 2019 consensus on MCS notes an association between the condition and Hashimoto's thyroiditis, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE), psoriasis and atopic eczema.[130][131][132][133]

Psychological

It has also been hypothesized that multiple chemical sensitivity is a psychological disorder. Psychosomatic, psychiatric and psychological theories of MCS, however, have not been accepted by the most recent medical consensus document on MCS,[2] and the hypothesis that MCS has psychological causes has flaws.[8][96][17][134][135][136][9][137]

The arguments used to support the hypothesis that MCS has psychological causes have been:

- there is no certainty about biological causes of MCS, therefore it must be psychological[138][139]

- that nocebo responses may operate in MCS,[140] and

- that people with MCS are more likely than controls to have anxiety, depression and the personality trait absorption.[141][142]

The 2019 Italian consensus on MCS concluded that the studies that hypothesize that the condition has a psychological cause "have been the object of strong criticism, both for methodological deficiencies as well as for the conflict of interests of the scientists who propose this thesis."[96] It said there was consensus that MCS reactions could cause psychiatric symptoms through biological processes (e.g. neurogenic inflammation) and that symptoms of the condition should not be mistaken for the cause.[96] It also highlighted that "it was researchers at Johns Hopkins University who pointed out that it is ineffective to use personality tests such as MMP2 (i.e. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory 2) for the study of the pathogenesis of environmental diseases...concluding that the presence of psychological-psychiatric symptoms in patients with MCS was compatible with the objective limitations imposed by the disease, rather than being the cause."[96][135][137]

Other researchers have emphasized that the psychosocial impacts of the disease (especially isolation and stigmatization) are likely to have significant impacts on mental health.[8]:48[137][135][143][14][144][145] One study showed that anxiety and depression typically started in people with MCS post onset of the condition.[146]

The presence of nocebo responses in MCS does not indicate that it is the cause of the disease.[147] Nocebo responses are found in many biologically caused conditions,[148] including asthma, and they have been shown to be especially pronounced in neurological conditions (including migraine and chronic pain).[149]

It is noteworthy that psychological approaches to care in MCS patients have had “very limited success,”[8]:48 and that neither MCS, MCS/ES nor IEI have been included in any edition of the DSM (American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual[150]) nor have they been listed among somatoform disorders in the International Classification of Diseases.[151]

In Canada, in 2017, following a three-year government inquiry into environmental illness, it was recommended that a public statement be made by the health department dispelling the misperception that MCS/ES is psychological.[8]:17

Genetic

The 2019 consensus on MCS said that the condition could, at least in part, be caused by genetic alterations affecting detoxification pathways—something which in combination with toxin exposures could make some people more vulnerable to developing MCS than the rest of the population.[96]

Recent Italian studies found that compared to controls, patients with MCS had higher levels of the nitrites and nitrates that are involved in oxidative stress and inflammatory processes, including those that contribute to the oxidative damage of DNA.[96] They also found that the presence of the following genetic polymorphisms were more likely in people with MCS than controls: NOS3, NOS2 and GPX1.[96][152][153]

Other genetic markers known to affect detoxification pathways have been identified as being more common in subjects with MCS than controls,[96][152][153][154][155][156] including polymorphisms and differences in expression of the following: CYP2D6, MTHFR, NAT1, NAT2, GSTM1, and PON1 and PON2.[157][158][159]

These findings could support the hypothesis that MCS is caused by a synergy of environmental exposures to toxic substances and the impaired ability to metabolize toxic substances, due to factors related to genetic predisposition.[96]

COVID-19 and Long COVID

There have been anecdotal reports of people with Long COVID, or chronic COVID, developing new allergies, including fragrance and other chemical sensitivities.[160]

ME/CFS and multiple chemical sensitivity

MCS has been called a common comorbidity of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) by several consensus documents:[161][162][163]

- The Canadian Consensus Criteria (2003) for ME/CFS lists "new sensitivities to food, medications and/or chemicals" as a symptom and MCS as a comorbidity;

- The International Consensus Criteria (2011) for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis lists "sensitivities to food, medications, odors or chemicals" as a symptom and MCS as a comorbidity; and

- The U.S. ME/CFS Clinician Coalition publication Diagnosing and Treating Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) (2020) lists "chemical sensitivity" as a symptom of ME/CFS, and MCS as a comorbidity.[164]

ME/CFS patients who also have MCS are more likely to face difficulties and complexities associated with accessing healthcare, supportive services and accommodation than those who don't. As well, if they have problems tolerating medications, this could complicate the management of their ME/CFS symptoms

Controversy

MCS sufferers and the physicians treating them have been subject to campaigns aimed at undermining the reality of the illness.[165] This has played out in academia and in the media—and, perhaps with the greatest impact on sufferers, on Wikipedia.[166][167][168][169][170][171][172][173] These efforts have created a perception that MCS is a controversial or disputed condition,[9][174] which is not supported by recent academic reviews of MCS research.[3][8][1][6][154]

Some say chemical industry interest groups have funded these efforts, and indeed some of the most vocal writers with anti-MCS stances have also been industry-paid expert witnesses in legal cases involving alleged chemical injuries.[175]

The blogs Quackwatch and Science-Based Medicine (SBM)—related blogs dominated by the same brand of skepticism—are two groups known to have repeatedly published criticism about MCS's recognition as a medical condition, claiming MCS was a "bogus", "fad" or "spurious" diagnosis.[169][176][177][178][179][180][181] Quackwatch's founder, retired psychiatrist Stephen Barrett, has personally written prolifically on the subject of MCS.[182][183][184][185][186][187][188][189][190][191][177][174]

Important contexts for these efforts are that: (1) legal actions—including defamation suits in the U.S.—have alleged that Quackwatch and Barrett have been actively and knowingly promoting inaccurate information on a range of medical conditions on Wikipedia[192][170][193] (of note, in 2003, a California Appeals Court, for example, found Quackwatch's founder “to be biased and unworthy of credibility”[194][193]); and (2) in academia, a 2019 consensus on MCS concluded that the studies that hypothesized MCS was a psychogenic disorder had been the object of strong criticism, in part, for "the conflict of interests of the scientists who proposed this thesis."[96]

While those who have argued that MCS isn't real or is psychologically caused have undoubtedly successfully influenced popular perceptions about the condition,[175] their commentaries are at odds with: (1) the current medical consensus about MCS,[1][5][6][8][16]:31[2][98]:11 (2) conclusions of the most recent academic reviews of MCS research in scientific journals,[1][6] and (3) the recognition of the condition by the WHO/ICPS[40] and by other national and state health agencies, physicians' organizations and hospitals.[1][7][21][16]:17[42][81][83][78][84][82][86][98]:11[50][195][196]

In the media

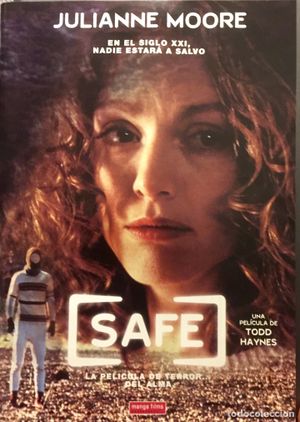

Safe (1995)

Safe is a cult horror film, by writer and director Todd Haynes, known for its depiction of MCS as a profoundly alienating and destabilizing condition.[198]

It tells the story of Carol White, played by Julianne Moore, a homemaker in Los Angeles, who suddenly develops a range of unexplained symptoms following the renovation of her home.

With severe symptoms, which doctors are unable to treat, and a largely indifferent and unsupportive community, Carol ultimately leaves her home and moves to a desert community for people with environmental illness.

“She is so excruciatingly alone,” Moore said of her character at the end of the film.[197] While Haynes said Carol’s isolation was both the answer and the problem for her.[198]

Early in the Covid-pandemic, Carol's isolation was compared to the psychosocial experience of lockdowns.[199].

Afflicted docuseries (2018)

Netflix's 2018 documentary series Afflicted features several patients with MCS.

After its release, Afflicted was accused of misrepresenting patients with chronic illnesses, with several people who featured in the series suing Neflix for defamation.[166]

An open letter to Netflix, signed by over 40 doctors, medical professionals and patient advocates, accused the media-services provider and production company of presenting flawed medical and scientific information. It also said unethical journalistic methods were used in the making of the series and called for it to be taken off Netflix.[200]

Notable studies and publications

- 1987, Cullen, M.R. The worker with multiple chemical sensitivities: An overview[201] - (Abstract)

- 1999, Multiple chemical sensitivity: a 1999 consensus[5] - (Full text)

- 2005, Multiple Chemical Sensitivity Syndrome (MCS) – suggestions for an extension of the US MCS-case definition[26] - (Abstract)

- 2014, Toxicant-Induced Loss of Tolerance: A Theory to Account for Multiple Chemical Sensitivity[99] (Full text)

- 2016, Association of Odor Thresholds and Responses in Cerebral Blood Flow of the Prefrontal Area during Olfactory Stimulation in Patients with Multiple Chemical Sensitivity[202] - (Full text)

- 2018, Multiple Chemical Sensitivity: Review of the State of the Art in Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Future Perspectives[1] - (Full text)

- 2018, Perspectives on multisensory perception disruption in idiopathic environmental intolerance: a systematic review[6] - (Abstract)

- 2019, Italian Consensus on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) -- Consensus Document and Guidelines on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS)[94] - (Full text - English)

- 2019, International prevalence of chemical sensitivity, co-prevalences with asthma and autism, and effects from fragranced consumer products[65] - (Full text)

- 2021, Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in exhaled breath as a marker of hypoxia in multiple chemical sensitivity[95] - (Full text)

- 2021, Mast cell activation may explain many cases of chemical intolerance[100] (Full text)

- 2021, Multiple Chemical Sensitivity[203] (Full text)

News articles and interviews

- 2017, The case against fragrance: The potential harm of our perfumed world - New Zealand Listener

- 2018, MCS--the condtion that affects one million Australia - SBS television, Australia (Video)

- 2019, Fragrance sensitivity: why perfumed products can cause profound health problems - The Guardian

- 2020, Common chemical products making Australians sick, study finds - Melbourne University Press

- 2020, Are scented cleaning products making you sick? - Stuff NZ

- 2021, The unusual headaches that upended this man's life began with a new car - The Washington Post

- 2021, Experts ‘disturbed’ over toxic discovery in popular makeup products[204] - Sydney Morning Herald

See also

- Toxicant-induced loss of tolerance (TILT)

- Mast cell activation syndrome

- Sick building syndrome

- Mold illness

- Gulf War Illness

- New allergies and intolerances

- Psychologization

Learn more

- Multiple Chemical Sensitivity[25] (book chapter) - Malcolm Hooper

- 2010, Allergies and Multiple Chemical Sensitivity in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome[205] - Margaret Williams

- 2019, Italian Consensus on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (English translation)

- Idiopathic environmental intolerance - MSD Manuals

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 Rossi, Sabrina; Pitidis, Alessio (February 2018). "Multiple Chemical Sensitivity: Review of the State of the Art in Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Future Perspectives". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 60 (2): 138–146. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001215. ISSN 1076-2752. PMC 5794238. PMID 29111991.

...some countries, such as Germany and Austria, and some agencies and provisions in the United States, such as the Environmental protection Agency (EPA) and the American Disability Act (ADA), have recognized this pathology.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Grouppo di Italiano Studio MCS (May 23, 2019). "2. Epidemiologia" [2. Epidemiology] (PDF). Consenso Italiano sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS). Documento di consenso e linee guida sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS) del Gruppo di Studio Italiano sulla MCS [Italian Consensus on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) -- Consensus Document and Guidelines on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) by the Italian Workgroup on MCS]. Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 Grouppo di Italiano Studio MCS (May 23, 2019). "1. Sensibilitá Chimica Multipla (MCS): Definizione di Caso" [1. Clinical features of the disease]. Consenso Italiano sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS). Documento di consenso e linee guida sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS) del Gruppo di Studio Italiano sulla MCS [Italian Consensus on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) -- Consensus Document and Guidelines on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) by the Italian Workgroup on MCS] (PDF). Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Grouppo di Italiano Studio MCS (May 23, 2019), "1.2 Scatenamento della MCS" [1.2 Triggering of MCS], Consenso Italiano sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS). Documento di consenso e linee guida sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS) del Gruppo di Studio Italiano sulla MCS [Italian Consensus on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) -- Consensus Document and Guidelines on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) by the Italian Workgroup on MCS] (PDF), Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 "Multiple chemical sensitivity: a 1999 consensus". Arch. Environ. Health. 54 (3): 147–9. 1999. doi:10.1080/00039899909602251. PMID 10444033.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 Viziano, A.; Micarelli, A.; Pasquantonio, G.; Della-Morte, D.; Alessandrini, M. (November 2018). "Perspectives on multisensory perception disruption in idiopathic environmental intolerance: a systematic review". Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 91 (8): 923–935. doi:10.1007/s00420-018-1346-z. PMID 30088144.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 National Industrial Chemicals Notification and Assessment Scheme; Office of Chemical Safety and Environmental Health (2010). A Scientific Review of Multiple Chemical Sensitivity: Identifying Key Research Needs. Canberra, Australia. ISBN 978-0-9807221-4-7. Archived from the original on November 2010.

Recognition of MCS as a disease and disability...In Germany, MCS is included in the alphabetical index of the German version of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10-SGB-V), first published in November 2000 by the German Institute of Medical Documentation and Information (DIMDI). At this stage, Austria has adopted the German ICD-10 for its use and therefore MCS is included also in the Austrian ICD-10

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 8.16 8.17 Task Force on Environmental Health (2017), Time for leadership: recognizing and improving care for those with ME/CFS, FM and ES/MCS. Phase 1 report. (PDF), Toronto, Ontario: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 Steinemann, Anne (March 2018). "National Prevalence and Effects of Multiple Chemical Sensitivities". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 60 (3): e152–e156. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001272. ISSN 1076-2752. PMC 5865484. PMID 29329146.

- ↑ Loria-Kohen, Viviana; Marcos-Pasero, Helena; de la Iglesia, Rocío; Aguilar-Aguilar, Elena; Espinosa-Salinas, Isabel; Herranz, Jesús; Ramírez de Molina, Ana; Reglero, Guillermo (August 22, 2017). "Multiple chemical sensitivity: Genotypic characterization, nutritional status and quality of life in 52 patients". Medicina Clinica. 149 (4): 141–146. doi:10.1016/j.medcli.2017.01.022. ISSN 1578-8989. PMID 28283271.

- ↑ Gibson, Pamela Reed; Leaf, Britney; Komisarcik, Victoria (January 12, 2016). "Unmet medical care needs in persons with multiple chemical sensitivity: A grounded theory of contested illness". Journal of Nursing Education and Practice. 6 (5): 75. doi:10.5430/jnep.v6n5p75. ISSN 1925-4059.

- ↑ García-Sierra, Rosa; Álvarez-Moleiro, María (July 1, 2014). "Evaluation of suffering in individuals with multiple chemical sensitivity". Clínica y Salud. 25 (2): 95–103. doi:10.1016/j.clysa.2014.06.006. ISSN 1130-5274.

- ↑ Alobid, Isam; Nogué, Santiago; Izquierdo-Dominguez, Adriana; Centellas, Silvia; Bernal-Sprekelsen, Manuel; Mullol, Joaquim (December 1, 2014). "Multiple chemical sensitivity worsens quality of life and cognitive and sensorial features of sense of smell". European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 271 (12): 3203–3208. doi:10.1007/s00405-014-3015-5. ISSN 1434-4726.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Gibson, PR; Vogel, VM (January 2009). "Sickness-related dysfunction in persons with self-reported multiple chemical sensitivity at four levels of severity". J Clin Nurs. 18 (1): 72–81. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02439.x.

- ↑ Koch, Lynn; Vierstra, Courtney; Penix, Ken (September 1, 2006). "A Qualitative Investigation of the Psychosocial Impact of Multiple Chemical Sensitivity". Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling. 37 (3): 33–40. doi:10.1891/0047-2220.37.3.33. ISSN 0047-2220.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 Valderrama Rodríguez, M; Revilla López, MC; Blas Diez, MP; Vázquez Fernández del Pozo, S; Martín Sánchez, Jl (2015). Actualización de la Evidencia Científica sobre Sensibilidad Química Múltiple (SQM) [Review of the scientific evidence on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity] (PDF). Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Instituto Aragonés de Ciencias de la Salud. Informes de Evaluación de Tecnologías Sanitarias (IACS).

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Genuis, SJ; Ross, PM; Whysner, J; Covello, VT; Kuschner, M; Rifkind, AB; Sedler, MJ; Trichopoulos, D (May 2013). "Chemical sensitivity: pathophysiology or pathopsychology? Is multiple chemical sensitivity a mental illness?". Clinical Therapeutics (Review). 35 (5): 572–7. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.04.003. PMID 23642291.

The emerging problem of ubiquitous adverse toxicant exposures in modern society has resulted in escalating numbers of individuals developing a CS disorder. As usual in medical history, iconoclastic ideas and emerging evidence regarding novel disease mechanisms, such as the pathogenesis of CS, have been met with controversy, resistance, and sluggish knowledge translation.

- ↑ Ross PM, Whysner J, Covello VT, Kuschner M, Rifkind AB, Sedler MJ, Trichopoulos D, Williams GM (1999). "Olfaction and Symptoms in the Multiple Chemical Sensitivities Syndrome". Preventive Medicine. 28 (5): 467–480. doi:10.1006/pmed.1998.0469. PMID 10329337.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Graveling RA, Pilkington A, George JP, Butler MP, Tannahill SN (1999). "A review of multiple chemical sensitivity". Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 56 (2): 73–85. doi:10.1136/oem.56.2.73. PMC 1757696. PMID 10448311.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Grenville, Kate (2017). The case against fragrance (1st ed.). Melbourne, Australia: The text publishing company. ISBN 9781925355956.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Centers for Disease Control Office of Health and Safety (2009), Indoor Environment Quality Policy (PDF), United States, p. 9

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Pall, Martin L. (2007). Explaining "Unexplained illnesses": Disease Paradigm for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Multiple Chemical Sensitivity, Fibromyalgia, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Gulf War Syndrome and Others. New York: Routledge & Harrington Park Press. ISBN 978-0789023896.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Ziem, Grace E. (April 24, 2018). "Multiple Chemical Sensitivity: Treatment and Followup with Avoidance and Control of Chemical Exposures". Toxicology and Industrial Health. doi:10.1177/074823379200800409.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Pigatto, Paolo D.; Guzzi, Gianpaolo (June 1, 2019). "Prevalence and risk factors for multiple chemical sensitivity in Australia". Preventive Medicine Reports. 14: 100856. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100856. ISSN 2211-3355.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Hooper, Malcolm (November 27, 2009). "Multiple Chemical Sensitivity" (PDF). In Puri, Bassant; Treasaden, Ian (eds.). Psychiatry: An evidence-based text. CRC Press. pp. 793–820. ISBN 978-1-4441-1326-6.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Lacour, Michael; Zunder, Thomas; Schmidtke, Klaus; Vaith, Peter; Scheidt, Carl (May 13, 2005). "Multiple Chemical Sensitivity Syndrome (MCS) – suggestions for an extension of the US MCS-case definition". International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 208 (3): 141–151. doi:10.1016/j.ijheh.2005.01.017. ISSN 1438-4639.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Tran, Marie Thi Dao; Arendt-Nielsen, Lars; Kupers, Ron; Elberling, Jesper (April 2013). "Multiple chemical sensitivity: On the scent of central sensitization" (PDF). International journal of hygiene and environmental health. 216 (2): 202–210. doi:10.1016/j.ijheh.2012.02.010. PMID 22487274.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Damiani, Giovanni; Alessandrini, Marco; Caccamo, Daniela; Cormano, Andrea; Guzzi, Gianpaolo; Mazzatenta, Andrea; Micarelli, Alessandro; Migliore, Alberto; Piroli, Alba; Bianca, Margherita; Tapparo, Ottaviano (October 27, 2021). "Italian Expert Consensus on Clinical and Therapeutic Management of Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS)". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 18 (21): 11294. doi:10.3390/ijerph182111294. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 8582949. PMID 34769816.

- ↑ Caress SM, Steinemann AC (May 2004). "Prevalence of Multiple Chemical Sensitivities: A Population-Based Study in the Southeastern United States". Am J Public Health. 94 (5): 746–747. doi:10.2105/ajph.94.5.746. PMC 1448331. PMID 15117694.

- ↑ Bloch, Richard M.; Meggs, William J. (January 1, 2007). "Comorbidity patterns of self‐reported chemical sensitivity, allergy, and other medical illnesses with anxiety and depression". Journal of Nutritional & Environmental Medicine. 16 (2): 136–148. doi:10.1080/13590840701352823. ISSN 1359-0847.

- ↑ Berg, Nikolaj Drimer; Linneberg, Allan; Dirksen, Asger; Elberling, Jesper (July 1, 2008). "Prevalence of self-reported symptoms and consequences related to inhalation of airborne chemicals in a Danish general population". International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 81 (7): 881–887. doi:10.1007/s00420-007-0282-0. ISSN 1432-1246.

- ↑ Andersson, Linus; Johansson, Åke; Millqvist, Eva; Nordin, Steven; Bende, Mats (October 1, 2008). "Prevalence and risk factors for chemical sensitivity and sensory hyperreactivity in teenagers". International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 211 (5): 690–697. doi:10.1016/j.ijheh.2008.02.002. ISSN 1438-4639.

- ↑ Gibson PR, Lockaby SD, Bryant JM (April 6, 2016). "Experiences of persons with multiple chemical sensitivity with mental health providers" (PDF). Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 9: 163–172.

- ↑ Steinemann, AC (2005). "A national population study of the prevalence of multiple chemical sensitivity". Arch Environ Health. 59 (6): 300–5.

- ↑ Caress, SM; Steinemann, AC (February 1, 2009). "Asthma and chemical hypersensitivity: prevalence, etiology, and age of onset". Toxicology and Industrial Health. 25 (1): 71–78. doi:10.1177/0748233709102713. ISSN 0748-2337.

- ↑ "Danimarca: nuovo codice per la MCS" [Denmark: A new code for MCS]. Infoamica (in italiano). October 14, 2014. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Elberling, Jesper; Bonde, Jens Peter Ellekilde; Vesterhauge, Søren; Bang, Søren; Linneberg, Allan; Zachariae, Claus; Johansen, Jeanne Duus; Blands, Jette; Skovbjerg, Sine (May 26, 2014). "Patienter med symptomer, der er relateret til dufte og kemiske stoffer, kan nu kodes specifikt med Sundhedsvæsenets Klassifikationssystem" [A new classification code is available in the Danish health-care classification system for patients with symptoms related to chemicals and scents]. Ugeskrift for Laeger (in dansk). 176 (11): V10120627. ISSN 1603-6824. PMID 25096843.

- ↑ Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) 2014, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Share File, Statistics Canada.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 Steinemann, A. (2018). "Prevalence and effects of multiple chemical sensitivities in Australia". Prev Med Rep. 10: 191–4. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.03.007. PMC 5984225. PMID 29868366.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 40.5 Schwenk, Michael (2004). "Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) - Scientific and Public-Health Aspects". GMS current topics in otorhinolaryngology, head and neck surgery. 3: Doc05. ISSN 1865-1011. PMC 3199799. PMID 22073047.

- ↑ World Health Organization; DIMDI (2011). ICD-10-GM Version 2012 : internationale statistische Klassifikation der Krankheiten und verwandter Gesundheitsprobleme (in Deutsch) (2012 ed.). Deutscher Ärzteverlag. p. 184. ISBN 978-3-7691-3481-0.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 Grouppo di Italiano Studio MCS (May 23, 2019). "4.1 "Innanzitutto, non nuocere": l'evitamento chimica ambientale" [4.1 "First, do no harm": environmental chemical avoidance]. Consenso Italiano sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS). Documento di consenso e linee guida sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS) del Gruppo di Studio Italiano sulla MCS [Italian Consensus on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) -- Consensus Document and Guidelines on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) by the Italian Workgroup on MCS] (PDF). Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy.

'Numerous legislative initiatives in the United States, Canada, Australia, Japan and Germany protect the right of MCS patients to work, education, safe housing and social participation through different protocols of environmental chemical avoidance...' [Translated from Italian]

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control (November 19, 2019). "Symptoms of ME/CFS | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Grouppo di Italiano Studio MCS (May 23, 2019). "4.2 Ausili terapeutici per soggetti con invalidità per MCS" [4.2 Therapeutic aids for subjects with disabilities for MCS]. Consenso Italiano sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS). Documento di consenso e linee guida sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS) del Gruppo di Studio Italiano sulla MCS [Italian Consensus on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) -- Consensus Document and Guidelines on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) by the Italian Workgroup on MCS] (PDF). Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 Grouppo di Italiano Studio MCS (May 23, 2019). "4.5 Terapia con ossigeno e camera iperbarica" [4.5 Oxygen therapy and hyperbaric oxygen]. Consenso Italiano sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS). Documento di consenso e linee guida sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS) del Gruppo di Studio Italiano sulla MCS [Italian Consensus on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) -- Consensus Document and Guidelines on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) by the Italian Workgroup on MCS] (PDF). Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy.

- ↑ Gibson, PR; Elms, AN; Ruding, LA (2003). "Perceived treatment efficacy for conventional and alternative therapies reported by persons with multiple chemical sensitivity". Environ Health Perspect. 111: 1498–1504.

- ↑ Horvath, I.; Loukides, S.; Wodehouse, T.; Kharitonov, S.A.; Cole, P.J.; Barnes, P.J. (October 1, 1998). "Increased levels of exhaled carbon monoxide in bronchiectasis: a new marker of oxidative stress". Thorax. 53 (10): 867–870. doi:10.1136/thx.53.10.867. ISSN 0040-6376. PMID 10193374.

- ↑ Ewing, James F.; Maines, Mahin D. (1993). "Glutathione Depletion Induces Heme Oxygenase-1 (HSP32) mRNA and Protein in Rat Brain". Journal of Neurochemistry. 60 (4): 1512–1519. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03315.x. ISSN 1471-4159.

- ↑ Gregersen, Per; Klausen, Hans; Elsnab, Charlotte Uldal (1987). "Chronic toxic encephalopathy in solvent-exposed painters in Denmark 1976–1980: Clinical cases and social consequences after a 5-year follow-up". American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 11 (4): 399–417. doi:10.1002/ajim.4700110403. ISSN 1097-0274.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (2007), Australian Human Rights Commission Access: Guidelines and information, Canberra

- ↑ "Guidelines on the Use of Perfumes and Scented Products". University of Toronto. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Flegel, Ken; Martin, James G. (November 3, 2015). "Artificial scents have no place in our hospitals". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 187 (16): 1187–1187. doi:10.1503/cmaj.151097. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 4627866. PMID 26438018.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 Scented products and fragrances policy Mount Sinai Hospital, Ontario, Canada.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Smoke Free, Scent Sensitive, Latex Sensitive. Kinston Health Sciences Centre. Canada. 2020.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Visiting the hospital. The Ottawa Hospital. Ottawa, Canada.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Souris Hospital Patient and Family Information Booklet 2017-2018 Prince Edward Island, Canada.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 St Joseph's healthcare scent free policy St Joseph's healthcare, Hamilton, Canada.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Scent free policy (2007). Markham Stouffville Hospital. Canada.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Scent-free policy. Mackenzie Health hospitals. MAD, Ontario, Canada

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Visiting CAMH Ontario, Canada.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Mission Memorial Hospital British Columbia, Canada

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Patient and Family Guide South Bruce Grey Health Center, Ontario, Canada.

- ↑ The campaign for safe cosmetics (2010). "Not so sexy. The health risks of secret ingredients in fragrance" (PDF). The Environmental Working Group. Section 1: Allergic Sensitivity to Fragrances: A Growing Health Concern.

- ↑ Steinemann, Anne; Goodman, Nigel (June 1, 2019). "Fragranced consumer products and effects on asthmatics: an international population-based study". Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health. 12 (6): 643–649. doi:10.1007/s11869-019-00693-w. ISSN 1873-9326.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Steinemann, Anne (May 1, 2019). "International prevalence of chemical sensitivity, co-prevalences with asthma and autism, and effects from fragranced consumer products". Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health. 12 (5): 519–527. doi:10.1007/s11869-019-00672-1. ISSN 1873-9326.

- ↑ Nazaroff, W.W. Welsher, C.J. Cleaning products and air fresheners: exposure to primary and secondary air pollutants. Atmos. Environ., 38 (2004), pp. 2841-2865

- ↑ Kumar, P.; Caradonna, V.M; Graham, S. Gupta, X. Cai, P.N. Rao, J. Thompson Inhalation challenge effects of perfume scent strips in patients with asthma, Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol., 75 (5) (1995), pp. 429-433

- ↑ Elberling J, Linneberg A, Mosbech H, Dirksen A, Frølund L, Madsen F, Nielsen NH, Johansen JD. 2004. A link between skin and airways regarding sensitivity to fragrance products? Br J Dermatol. 151(6): 1197-203.

- ↑ Elberling J, Lerbaek A, Kyvik KO, Hjelmborg J. A twin study of perfume related respiratory symptoms. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2009; 212(6): 670-8.

- ↑ Mendell. M.J. Indoor residential chemical emissions as risk factors for respiratory and allergic effects in children: a review. Indoor Air. 2007; 17(4):259-77.

- ↑ Schnuch A, Oppel E, Oppel T, Römmelt H, Kramer M, Riu E, Darsow U, Przybilla B, Nowak D, Jörres RA. 2010. Experimental inhalation of fragrance allergens in predisposed subjects: effects on skin and airways. Br J Dermatol.

- ↑ Neuenschwander U, Guignard F, Hermans I. 2010. Mechanism of the aerobic oxidation of alpha-pinene. ChemSusChem. 3(1): 75-84.

- ↑ Nielsen GD, Larsen ST, Hougaard KS, Hammer M, Wolkoff P, Clausen PA, Wilkins CK, Alarie Y. 2005. Mechanisms of acute inhalation effects of (+) and (-)-alpha-pinene in BALB/c mice. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 96(6):420-8.

- ↑ Rohr AC, Wilkins CK, Clausen PA, Hammer M, Nielsen GD, Wolkoff P, Spengler JD. 2002. Upper airway and pulmonary effects of oxidation products of (+)-alpha-pinene, d-limonene, and isoprene in BALB/c mice. Inhal Toxicol. 14(7): 663-84.

- ↑ Venkatachari P, Hopke PK. 2008. Characterization of products formed in the reaction of ozone with alpha-pinene: case for organic peroxides. J Environ Monit. 10(8): 966-74.

- ↑ The Environmental Health Association of Quebec (2020). "Impacts of Covid-19 Health measures on people with multiple chemical sensitivities".

- ↑ Grouppo di Italiano Studio MCS (May 23, 2019), "5. Osdepali per MCS" [5. Hospitals and MCS], [The Italian Consensus] Consenso Italiano sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS). Documento di consenso e linee guida sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS) del Gruppo di Studio Italiano sulla MCS [[Italian Consensus on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) -- Consensus Document and Guidelines on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) by the Italian Workgroup on MCS]] (PDF), Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 78.2 "Mercy Medical Center Process Standards, Multiple Chemical Sensitivity Protocol". Mercy Medical Centers New York and California. September 1999.

- ↑ Anaesthesia for patients with idiopathic environmental intolerance and chronic fatigue syndrome. Br J Anaesth 2008; 101(4): 486-91.]

- ↑ Rea, William J. (1996). "41 Surgery in the chemically sensitive". In Environmental Health Center (ed.). Chemical Sensitivity Tools of Diagnosis and Methods of Treatment. IV. Dallas, Texas: CRC Press. pp. 2803–2850. ISBN 0873719654.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 81.2 "Multiple Chemical Sensitivity -- A guide for Victoria hospitals", Victoria Department of Health, August 25, 2011

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 ACT Department of Health, Canberra, Australia (2018). "Canberra Hospital and Health Services Clinical Procedure: Multiple Chemical Sensitivities".

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 NSW Health (September 2, 2015). "Fact sheet: Multiple Chemical Sensitivity Disorder". NSW Health. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (2017). "National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards Guide for Hospitals" (PDF). Canberra, Australia: NSW health.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 "Idiopathic Environmental Intolerance or Multiple Chemical Sensitivity Policy Guideline" (PDF). South Australia Health. Adelaide, Australia. August 26, 2016.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 86.2 "Multiple Chemical Sensitivity Chemical Hypersensitivity Guideline" (PDF). Western Australia Country Health Service. September 14, 2010.

- ↑ Multiple Chemical Sensitivities. Jan 2010. QHC Healthcare, Ontario, Canada.

- ↑ Johnson, Alison (November 20, 2008). "The Elusive Search for a Place to Live" (PDF). Amputated Lives: Coping with Chemical Sensitivity (1st ed.). Parramatta, Australia: Cumberland Press. pp. 16–26.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 Environmental Health Coalition (March 11, 2002), Homelessness at critical level for Western Massachusetts chemically injured, Western Massachusetts

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 Martin, Sharyn (September 2020), Australian National Register of Environmental Sensitivities Submission to a New National Disability Strategy, p. 2

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Gibson, Pamela (January 1, 2016). "A Review of the Life Impacts of Environmental Sensitivities". Internal Medicine Review (May): 9. doi:10.18103/imr.v0i2.63.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 92.2 The Legal Rights and Challenges Faced by Persons with Chronic Disability Triggered by Environmental Factors. Report prepared by ARCH Disability Law Centre and the Canadian Environmental Law Association. September 2019

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 93.2 93.3 "An Action Plan to Improve Care for People with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS), Fibromyalgia (FM) and Environmental Sensitivities/Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (ES/MCS)" (PDF). Ottawa, Canada: Final Report of the Task Force on Environmental Health. December 2018.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 Grouppo di Italiano Studio MCS (May 23, 2019), Consenso Italiano sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS). Documento di consenso e linee guida sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS) del Gruppo di Studio Italiano sulla MCS [Italian Consensus on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) -- Consensus Document and Guidelines on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) by the Italian Workgroup on MCS] (PDF), Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 95.2 Mazzatenta, Andrea; Pokorski, Mieczyslaw; Giulio, Camillo Di (2021). "Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in exhaled breath as a marker of hypoxia in multiple chemical sensitivity". Physiological Reports. 9 (18): e15034. doi:10.14814/phy2.15034. ISSN 2051-817X. PMC 8449310. PMID 34536058.

- ↑ 96.00 96.01 96.02 96.03 96.04 96.05 96.06 96.07 96.08 96.09 96.10 96.11 96.12 96.13 96.14 96.15 96.16 96.17 96.18 96.19 Grouppo di Italiano Studio MCS (May 23, 2019), "1.4 Meccanismo proposti per la MCS" [1.4 Proposed mechanisms for MCS], Consenso Italiano sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS). Documento di consenso e linee guida sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS) del Gruppo di Studio Italiano sulla MCS [Italian Consensus on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) -- Consensus Document and Guidelines on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) by the Italian Workgroup on MCS] (PDF), Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 97.2 Royal Australasian College of Physicians' Submission to the Australian Parliament’s Health, Aged Care and Sport Committee Inquiry into Biotoxin-related Illnesses in Australia, Aug 2018. “Dr Graeme Edwards represented the RACP at this public hearing and we trust the Committee benefited from his contribution to the discussions.” p.1.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 98.2 98.3 98.4 Biotoxin related illnesses in Australia, comments by Dr Graeme Edwards, Official Committee of the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health, Aged Care and Sport, Canberra: House of Representatives, Hansard Records, August 9, 2018

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 Horowitz, Sala (April 2014). "Toxicant-Induced Loss of Tolerance: A Theory to Account for Multiple Chemical Sensitivity". Alternative and Complementary Therapies. 20 (2): 96–100. doi:10.1089/act.2014.20201. ISSN 1076-2809.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 Miller, Claudia S.; Palmer, Raymond F.; Dempsey, Tania T.; Ashford, Nicholas A.; Afrin, Lawrence B. (November 17, 2021). "Mast cell activation may explain many cases of chemical intolerance". Environmental Sciences Europe. 33 (1): 129. doi:10.1186/s12302-021-00570-3. ISSN 2190-4715.

- ↑ Pall, Martin L.; Satterlee, JD (2001). "Elevated nitric oxide/peroxynitrite mechanism for the common etiology of multiple chemical sensitivity, chronic fatigue syndrome, and Post Traumatic stress disorder". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 933 (1): 323–9. Bibcode:2001NYASA.933..323P. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05836.x. PMID 12000033.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 Bell, Iris R.; Baldwin, Carol M.; Fernandez, Mercedes; Schwartz, Gary E.R. (April 1, 1999). "Neural sensitization model for multiple chemical sensitivity: overview of theory and empirical evidence". Toxicology and Industrial Health. 15 (3–4): 295–304. doi:10.1177/074823379901500303. ISSN 0748-2337.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 Bell, IR; Rossi, J; Gilbert, ME; Kobal, G; Morrow, LA; Newlin, DB; Sorg, BA; Wood, RW (March 1, 1997). "Testing the neural sensitization and kindling hypothesis for illness from low levels of environmental chemicals". Environmental Health Perspectives. 105 (suppl 2): 539–547. doi:10.1289/ehp.97105s2539. PMC 1469815. PMID 9167993.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 104.2 Meggs, William J. (May 9, 2017). "The Role of Neurogenic Inflammation in Chemical Sensitivity". Ecopsychology. 9 (2): 83–89. doi:10.1089/eco.2016.0045.

- ↑ Grouppo di Italiano Studio MCS (May 23, 2019), "4.3" [4.3 Reduction of risk], Consenso Italiano sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS). Documento di consenso e linee guida sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS) del Gruppo di Studio Italiano sulla MCS [Italian Consensus on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) -- Consensus Document and Guidelines on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) by the Italian Workgroup on MCS] (PDF), Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy

- ↑ Reid, S; Hotopf, M; Hull, L; Ismail, K; Unwin, C; Wessely, S (2001). "Multiple Chemical Sensitivity and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome in British Gulf War Veterans". American Journal of Epidemiology. 153 (6): 604–9. doi:10.1093/aje/153.6.604. PMID 11257069.

- ↑ Gronseth, Gary S (May 1, 2005). "Gulf war syndrome: a toxic exposure? A systematic review". Neurologic clinics. 23 (2): 523–540. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2004.12.011. ISSN 1557-9875. PMID 15757795.

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense (October 2014). "Clinical practice guideline for the management of chronic multisystem illness" (PDF).

- ↑ Spelman, Juliette F.; Hunt, Stephen C.; Seal, Karen H.; Burgo-Black, A. Lucile (September 1, 2012). "Post Deployment Care for Returning Combat Veterans". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 27 (9): 1200–1209. doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2061-1. ISSN 1525-1497. PMC 3514997. PMID 22648608.

- ↑ Rea, William J. (June 1, 2018). "A Large Case-series of Successful Treatment of Patients Exposed to Mold and Mycotoxin". Clinical Therapeutics. 40 (6): 889–893. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.05.003. ISSN 0149-2918.

- ↑ Lieberman, Allan; Rea, William; Curtis, Luke (September 1, 2006). "Adverse health effects of indoor mold exposure". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 118 (3): 763. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2006.06.037. ISSN 0091-6749. PMID 16950304.

- ↑ Vojdani, Aristo; Thrasher, Jack D.; Madison, Roberta A.; Gray, Michael R.; Heuser, Gunnar; Campbell, Andrew W. (July 1, 2003). "Antibodies to Molds and Satratoxin in Individuals Exposed in Water-Damaged Buildings". Archives of Environmental Health: An International Journal. 58 (7): 421–432. doi:10.1080/00039896.2003.11879143. ISSN 0003-9896. PMID 15143855.

- ↑ Hänninen, Otto O. (2001). "World Health Organisation (WHO) Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: dampness and mold.". In Adan, Olaf C. G.; Samson, Robert A. (eds.). Fundamentals of mold growth in indoor environments and strategies for healthy living. Wageningen: Academic Publishers. pp. 277–302. doi:10.3920/978-90-8686-722-6_10. ISBN 978-90-8686-722-6.

Toxicological evidence obtained in vivo and in vitro supports these findings, showing the occurrence of diverse inflammatory and toxic responses after exposure to microorganisms – including their spores, metabolites and components isolated from damp buildings. The increasing prevalence of asthma and allergies in many countries increase the number of people susceptible to the effects of dampness and mould in buildings.

- ↑ Knibbs, Luke D.; Woldeyohannes, Solomon; Marks, Guy B.; Cowie, Christine T. (2018). "Damp housing, gas stoves, and the burden of childhood asthma in Australia". Medical Journal of Australia. 208 (7): 299–302. doi:10.5694/mja17.00469. ISSN 1326-5377.

Exposure to damp housing and gas stoves is common in Australia, and is associated with a considerable proportion of the childhood asthma burden.

- ↑ Quansah, Reginald; Jaakkola, Maritta S.; Hugg, Timo T.; Heikkinen, Sirpa A M.; Jaakkola, Jouni J.K. (November 7, 2012). "Residential Dampness and Molds and the Risk of Developing Asthma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". PLoS ONE. 7 (11): e47526. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047526. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3492391. PMID 23144822.

- ↑ Mendell, Mark J; Mirer, Anna G; Cheung, Kerry; Tong, My; Douwes, Jeroen (June 1, 2011). "Respiratory and Allergic Health Effects of Dampness, Mold, and Dampness-Related Agents: A Review of the Epidemiologic Evidence". Environmental Health Perspectives. 119 (6): 748–756. doi:10.1289/ehp.1002410. PMC 3114807. PMID 21269928.

The authors reported evidence from epidemiologic studies and meta-analyses showed indoor dampness or mould to be associated consistently with increased asthma development and exacerbation, current and ever diagnosis of asthma, dyspnoea, wheeze, cough, respiratory infections, bronchitis, allergic rhinitis, eczema, and upper respiratory tract symptoms. Associations were found in allergic and non-allergic individuals. Evidence strongly suggested causation of asthma “exacerbation” in children.

- ↑ Schwartz, G E; Bell, I R; Dikman, Z V; Fernandez, M; Kline, JP; Peterson, JM; Wright, KP (July 1, 1994). "EEG responses to low-level chemicals in normals and cacosmics". Toxicology and industrial health. 10 (4–5): 633–643. ISSN 1477-0393. PMID 7778120.

- ↑ Bell, Iris R; Schwartz, Gary E; Hardin, Elizabeth E; Baldwin, Carol M; Kline, John P (March 1, 1998). "Differential Resting Quantitative Electroencephalographic Alpha Patterns in Women with Environmental Chemical Intolerance, Depressives, and Normals". Biological Psychiatry. 43 (5): 376–388. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(97)00245-X. ISSN 0006-3223.

- ↑ Callender, Thomas James; Morrow, Lisa; Subramanian, Kodanallur (March 1, 1994). "Evaluation of chronic neurological sequelae after acute pesticide exposure using spect brain scans". Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. 41 (3): 275–284. doi:10.1080/15287399409531843. ISSN 0098-4108. PMID 8126750.

- ↑ Callender, Thomas J.; Morrow, Lisa; Subramanian, Kodanallur; Duhon, Dan; Ristovv, Mona (January 1, 1994). "Three-Dimensional Brain Metabolic Imaging in Patients with Toxic Encephalopathy. Presented at the Fourth International Symposium on Neurobehavioral Methods and Effects in Occupational and Environmental Health, July 8–11, 1991, Tokyo, Japan.". In Araki, Shunichi (ed.). Neurobehavioral Methods and Effects in Occupational and Environmental Health. Academic Press. pp. 451–475. ISBN 978-0-12-059785-7.

- ↑ Heuser, G; Mena, I; Alamos, F (July 1, 1994). "NeuroSPECT findings in patients exposed to neurotoxic chemicals". Toxicology and industrial health. 10 (4–5): 561–571. ISSN 1477-0393. PMID 7778114.

- ↑ Hillert, Lena; Musabasic, Vildana; Berglund, Hans; Ciumas, Carolina; Savic, Ivanka (2007). "Odor processing in multiple chemical sensitivity". Human Brain Mapping. 28 (3): 172–182. doi:10.1002/hbm.20266. ISSN 1097-0193. PMC 6871299. PMID 16767766.

- ↑ Ross, Gerald H.; Rea, William J.; Johnson, Alfred R.; Hickey, David C.; Simon, Theodore R. (April 1, 1999). "Neurotoxicity in single photon emission computed tomography brain scans of patients reporting chemical sensitivities†". Toxicology and Industrial Health. 15 (3–4): 415–420. doi:10.1177/074823379901500316. ISSN 0748-2337.

- ↑ Alessandrini, Marco; Micarelli, Alessandro; Chiaravalloti, Agostino; Bruno, Ernesto; Danieli, Roberta; Pierantozzi, Mariangela; Genovesi, Giuseppe; Öberg, Johanna; Pagani, Marco; Schillaci, Orazio (March 1, 2016). "Involvement of Subcortical Brain Structures During Olfactory Stimulation in Multiple Chemical Sensitivity". Brain Topography. 29 (2): 243–252. doi:10.1007/s10548-015-0453-3. ISSN 1573-6792.

- ↑ Chiaravalloti, Agostino; Pagani, Marco; Micarelli, Alessandro; Di Pietro, Barbara; Genovesi, Giuseppe; Alessandrini, Marco; Schillaci, Orazio (April 1, 2015). "Cortical activity during olfactory stimulation in multiple chemical sensitivity: a 18F-FDG PET/CT study". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 42 (5): 733–740. doi:10.1007/s00259-014-2969-2. ISSN 1619-7089.

- ↑ Albright, Joseph F.; Goldstein, Robert A. (September 1992). "Is There Evidence of an Immunologic Basis for Multiple Chemical Sensitivity?". Toxicology and Industrial Health. 8 (4): 215–219. doi:10.1177/074823379200800420. ISSN 0748-2337.

- ↑ Meggs, William J. (July 1992). "Multiple Chemical Sensitivities and the Immune System". Toxicology and Industrial Health. 8 (4): 203–214. doi:10.1177/074823379200800419. ISSN 0748-2337.

- ↑ Labarge, Andrew S.; McCaffrey, Robert J. (December 1, 2000). "Multiple Chemical Sensitivity: A Review of the Theoretical and Research Literature". Neuropsychology Review. 10 (4): 183–211. doi:10.1023/A:1026460726965. ISSN 1573-6660.

- ↑ 129.0 129.1 Belpomme, Dominique; Campagnac, Christine; Irigaray, Philippe (December 1, 2015). "Reliable disease biomarkers characterizing and identifying electrohypersensitivity and multiple chemical sensitivity as two etiopathogenic aspects of a unique pathological disorder". Reviews on Environmental Health. 30 (4): 251–271. doi:10.1515/reveh-2015-0027. ISSN 2191-0308.

- ↑ Grouppo di Italiano Studio MCS (May 23, 2019), "3.11" [3.11 Rheumatological evaluation], Consenso Italiano sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS). Documento di consenso e linee guida sulla Sensibilita Chimica Multipla (MCS) del Gruppo di Studio Italiano sulla MCS [Italian Consensus on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) -- Consensus Document and Guidelines on Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) by the Italian Workgroup on MCS] (PDF), Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy

- ↑ Hybenova, Monika; Hrda, Pavlina; Procházková, Jarmila; Stejskal, Vera; Sterzl, Ivan (2010). "The role of environmental factors in autoimmune thyroiditis". Neuro Endocrinology Letters. 31 (3): 283–289. ISSN 0172-780X. PMID 20588228.

- ↑ Ziem, G.; McTamney, J. (March 1, 1997). "Profile of patients with chemical injury and sensitivity". Environmental Health Perspectives. 105 (suppl 2): 417–436. doi:10.1289/ehp.97105s2417. PMC 1469804. PMID 9167975.

- ↑ Nogué, Santiago; Fernández-Solá, Joaquim; Rovira, Elisabet; Montori, Elisabet; Fernández-Huerta, José Manuel; Munné, Pere (June 1, 2007). "Sensibilidad química múltiple: análisis de 52 casos" [Multiple chemical sensitivity: study of 52 cases]. Medicina clinica (in español). 129 (3): 96–9. doi:10.1157/13107370. ISSN 1578-8989. PMID 17594860.