Enterovirus

Enterovirus is a genus of positive-sensed single-stranded RNA viruses. Viruses in the enterovirus genus include coxsackievirus A, coxsackievirus B, echovirus, poliovirus, rhinovirus, and many others.[1] Person-to-person transmission of enteroviruses occurs through fecal-oral and oral-oral routes.[2]

Enteroviruses are responsible for a range of acute infections and illnesses. They cause about 10 to 15 million infections and tens of thousands of hospitalizations each year in the United States.[3] But acute enterovirus infections can often be mild (like a common cold) or asymptomatic when contracted.[4][5]

Though normally only capable of acute infections, under certain circumstances enteroviruses can create chronic infections, and ongoing enterovirus infections have been found in ME/CFS and several other chronic illnesses in including dilated cardiomyopathy, and type 1 diabetes. Some researchers posit that such persistent enterovirus infections may be a cause of these diseases.

Enterovirus species

In the new classification system, the enterovirus genus contains 15 species of enterovirus named enterovirus A to L and rhinovirus A to C. Enterovirus A to D infect humans, and are the enterovirus species of clinical significance. The enterovirus B species contains the coxsackievirus B and echovirus serotypes which are associated with ME/CFS.

- Enterovirus A — contains some of the coxsackievirus A serotypes as well as enterovirus A71 (also written enterovirus 71).

- Enterovirus B — includes the six coxsackievirus B and 28 echovirus serotypes, as well as coxsackievirus A9.

- Enterovirus C — contains further coxsackievirus A serotypes as well as the three polioviruses.

- Enterovirus D — contains enterovirus D68, the virus recently linked to causing childhood paralysis.

- Enterovirus E to L — do not infect humans.

- Rhinovirus A to C — rhinovirus is a common cold virus.

The enterovirus genus is part of the picornavirus family (Picornaviridae).

Enterovirus serotypes

Poliovirus

Poliovirus is the cause of the paralytic disease known as poliomyelitis.[6] A study of poliovirus found that polio infection rapidly decreases cellular oxygen consumption (and thus energy production through cellular respiration) by inhibiting succinate dehydrogenase and blocking mitochondrial electron transport.[7]

Coxsackievirus

Coxsackie A virus

Coxsackie B virus

Coxsackie B (also written coxsackievirus B) is a group of six types of enterovirus, causing symptoms ranging from gastrointestinal distress to pericarditis and myocarditis. Symptoms of infection with viruses in the Coxsackie B grouping include fever, headache, sore throat, gastrointestinal distress, extreme fatigue as well as chest and muscle pain. It can also lead to muscle spasm in arms and legs. Numerous studies have found evidence of persistent infection of Coxsackie B in the blood, muscle, gut and brain in a subset of patients with diagnosed with myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15]

Echovirus

There are 32 human echoviruses. Like coxsackievirus B, these viruses can cause chronic low-level infections, and are associated with myalgic encephalomyelitis.

EV-D68

EV-D68 is a non-polio enterovirus, which has been linked to acute flaccid myelitis, a rare but serious neurological illness usually affecting children.[16]

Acute enterovirus infections

Enteroviruses can infect a wide array of organs in the body, and thus a given enterovirus serotype may cause a variety of different acute infections, and its symptoms in one person can be quite different to the symptoms it creates in the next person.

During the acute phase of infection, enteroviruses may produce one or more of the following symptoms and illnesses:[17][18][19]

- Respiratory — rhinosinusitis, pharyngitis, bronchitis, bronchiolitis, pleurisy, pneumonia.

- Gastrointestinal — vomiting, diarrhea, gastritis, terminal ileitis, colitis, hepatitis, pancreatitis, GERD, functional dyspepsia.

- Immune manifestations — prolonged Fevers (102 to 104°F, or 39 to 40°C) lasting 3 weeks, leukopenia, lymphopenia, bone marrow failure.

- Central nervous system — meningitis, encephalitis, myelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, epidemic vertigo and deafness.

- Cardiovascular — myocarditis, pericarditis, myopericarditis, endocarditis.

- Musculoskeletal — acute myositis, rhabdomyolysis, arthralgia and arthritis, pleurodynia (Bornholm disease).

- Genito-urinary tract — epididymitis, orchitis, salpingitis (fallopian tube inflammation), prostatitis.

- Skin — vesicles, maculopapular rash, petechiae, urticaria, vasculitis.

- Oral — enanthem (rash on the mucous membranes), herpangina, tongue and mouth ulcers.

- Other illnesses — hand, foot, and mouth disease, hemorrhagic conjunctivitis, poliomyelitis, inflammatory muscle disease.

Note that enterovirus is able to mimic a chickenpox rash: if a patient previously had chickenpox, and then develops a flu-like illness with a chickenpox-like rash, that is likely due to enterovirus. But an enterovirus rash can also look like measles, German measles (rubella) and can look like hives.[20] Enteroviruses are the only group of viruses able to routinely infect the muscles, heart and central nervous system. Other viruses can infect one or two of these organs, but not all three.[21][22]

The incubation period (time between catching the virus and the appearance of its first acute symptoms) for coxsackie viruses is three to five days,[23] and the incubation period for echovirus is two to 14 days.[24]

Coxsackievirus B (serotypes B2 to B5) and echoviruses account for more than 90% of causes of viral (aseptic) meningitis.[25] Evidence of enteroviral infection in the myocardium or endocardium tissues of the heart is detected in 40% of those who died suddenly of a heart attack, though it is not clear whether enterovirus causes these heart attacks.[26] Another study found 26% of heart attack patients had serological evidence of a very recent coxsackievirus B infection.[27]

Chronic enterovirus infections

Like most RNA viruses, enterovirus is not capable of assuming a latent state within cells, and enterovirus infections are generally considered to be acute and rapidly cleared by the host immune response.[28][29] Indeed, John Chia points out that even today, most physicians are taught that enterovirus does not form chronic infections.[30]

However, it is now understood that enterovirus B serotypes such as coxsackievirus B and echovirus are capable of mutating during the acute infection into an aberrant viral form called non-cytolytic enterovirus that can cause persistent low-level infections. These persistent non-cytolytic enterovirus infections deriving from mutated enterovirus B serotypes are found in ME/CFS and several other chronic illnesses, including chronic myocarditis, dilated cardiomyopathy, type 1 diabetes, amytrophic lateral sclerosis (motor neuron disease) and Parkinson's disease.

Non-cytolytic enterovirus consists of mutated naked viral RNA which produces persistent intracellular infections inside host cells, and does not readily kill the cells in which it resides. Although this infection replicates very slowly, it nevertheless produces all the normal viral proteins, and these proteins may have pathological disease-causing effects in the host. Persistent non-cytolytic enterovirus is resistant to immune clearance, and can thus reside inside host cells for very long periods. Non-cytolytic enterovirus infections are characterized by a decreased ratio of positive to negative strand viral RNA: whereas in normal acute enterovirus infections, this ratio is around 100:1, in persistence non-cytolytic infections, the ratio has a value closer to 1:1.

Diagnosis of chronic enterovirus infections

Dr John Chia uses the following tests to detect chronic enterovirus infection in ME/CFS patients:[31]

ARUP Lab micro-neutralization blood tests for enterovirus antibodies. Titers of 1:160 to 1:320 or higher on the ARUP Lab coxsackievirus B test and echovirus test suggest chronic active infection. These tests use the very sensitive gold standard neutralization method of measuring antibody levels. The ARUP lab test will indicate which particular enterovirus serotypes are present and active in the patient (out of coxsackievirus B1 to B6, and echovirus 6, 7, 9, 11, and 30). Other methods of antibody levels such as ELISA or IFA are less sensitive, and thus may not be reliable. The CFT method of testing for enterovirus antibodies is insensitive and useless for chronic enterovirus infection.[32]

Stomach biopsy (immunohistochemistry). This test, which requires a sample of stomach tissue obtained by an endoscope and to be sent to Dr Chia's lab for analysis, is the most sensitive for detecting a chronic enteroviral infection, although unlike the ARUP Lab blood tests, the stomach biopsy will not indicate which particular CVB and EV serotypes you have.

Note that PCR testing of the blood is not considered sensitive for chronic enterovirus infections. Since viruses are cleared quickly from the bloodstream, the chance of finding viral gene or RNA in the blood by reverse transcription-PCR technique is low in chronic infection. Dr Chia found that with special techniques and repeated testing, enterovirus RNA can be found in close to thirty percent of whole blood samples taken from chronically infected EV patients.

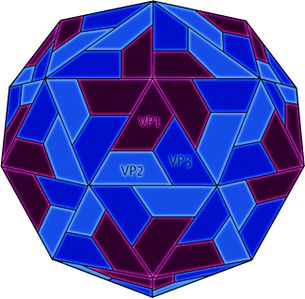

Dr Chia says that a fairly reliable sign of chronic enterovirus infection of the abdomen in ME/CFS patients is abdominal tenderness or pain in the epigastric area, in the right lower quadrant, and in the left lower quadrant (see the three X's in the abdomen picture). Epigastric pain or tenderness indicates enterovirus infection of the stomach. Right lower quadrant pain or tenderness suggests enterovirus infection of the terminal ileum. Left lower quadrant pain or tenderness suggests enterovirus infection in the small bowel or colon.[33][34]

Enterovirus in myalgic encephalomyelitis

Ever since the historic outbreaks of ME/CFS in the 1930s-1970s, enteroviruses, especially Coxsackie B viruses, have been posited as a key etiological factor in myalgic encephalomyelitis. These frequently coincided with outbreaks of polio, another enterovirus. Findings in several outbreaks seemed to suggest that symptoms were caused by a virus distinct from but related to polio including findings of mild, diffuse peripheral nervous system damage in monkeys infected with the virus; a stronger response to polio vaccination in children who had been in epidemic areas; and seasonal patterns of infection resembling polio.[35]

In addition to data from ME/CFS outbreaks, there have been over 30 studies on enterovirus infections in ME/CFS (see list of enterovirus infection studies), and most studies have found enterovirus present in ME/CFS patients' muscle tissues, stomach tissues, brain tissues and blood cells (though a few studies have failed to find enterovirus in ME/CFS). The chronic enterovirus infections found in ME/CFS have been shown to be of the non-cytolytic form (a reduced ratio of positive to negative strand viral RNA is found in the infections in ME/CFS patients' tissues, which is a signature of non-cytolytic infection).[36]

Evidence for enterovirus infection in ME/CFS

Antibody testing

Elevated Coxsackie B antibodies have been found in patients in at least two ME outbreaks.[37][38] In a retrospective cohort study[39] by Melvin Ramsay and Elizabeth Dowsett, 31% of the patients were found to have elevated enteroviral IgM antibody levels. Sixteen of these patients were retested annually over three years and all showed persistently elevated Coxsackie B neutralizing antibody levels and intermittently positive enteroviral IgM, suggesting a persistent infection was present.

Similarly, a study of of 76 patients with postviral fatigue syndrome (PVFS) found that 76% had detectible IgM responses to enteroviruses. 22% had positive cultures (compared to 7% controls) and VP1 antigen was detected in 51%, all pointing to a chronic infection in many post-viral patients.[40] However, a larger study in Scotland of 243 PVFS patients and matched controls found no difference in IgM and IgG positivity between patients and controls.[41]

Through antibody testing, Dr John Chia observes that the coxsackievirus B (CVB) and echovirus (EV) serotypes most often found in ME/CFS are:

- CVB3 and CVB4 first and foremost

- Then CVB2, EV6, EV7 and EV9

- And then much less EV11

Dr Chia finds that ME/CFS patients have antibody titers for the above enterovirus serotypes at significantly levels higher than those found in healthy controls, which is suggestive of chronic active infection. But Dr Chia points out that ME/CFS patients may have chronic infections with enteroviruses that cannot be detected and typed by antibody blood tests (but which are detectable by stomach tissue biopsy).

Polymerase chain reaction

In a study of serum samples from 100 CFS patients and 100 healthy controls, 42% of patients were positive for Coxsackie B sequences by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), compared to only 9% of the comparison group.[42]

Also using PCR, a study of 236 patients by John Chia found enteroviral RNA in 48% of patients as compared to 8% of controls.To date, Chia reports finding enteroviral RNA in 35% of 518 patients.[43]

Muscle biopsy

Several muscle biopsy studies have also found the presence of Coxsackie B RNA sequences in CFS patients as compared to controls. A study of 60 PVFS patients found 53% had enteroviral RNA in muscle compared to 15% of controls.[44] However, a follow-up study comparing CFS patients to patients with other neuromuscular disorders failed to find a statistically significant difference.[45]

Gut biopsy

Research by John Chia and his son, Andrew Chia has looked for enteroviruses in gut biopsies. Eighty-two percent of samples were positive for viral capsid protein 1 (VP1), compared to 20% of controls. Enteroviral RNA was detected in 37% of biopsy samples, compared to 4.7% of controls. They posit that a subset of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) patients have a chronic enteroviral infection.[46]

Brain autopsy

Three post-mortem studies have found enterovirus infections in the brains of ME/CFS patients.

Other conditions

Type 1 Diabetes

Several studies have suggested a relationship between Coxsackie B4 and the onset of type 1 diabetes.[47][48][49]

A study of patients with Type 1 Diabetes found that Coxsackie B4 was found to infect the β cells in the pancreatic islets of the pancreas and cause inflammation mediated by natural killer cells (NKC).[50]

Gastroparesis

A very small observational study found that nine out of ten patients with symptoms of gastroparesis had positive gastric biopsies for enterovirus.[51]

Treatment

There are no FDA approved treatments for enteroviruses. The drug Pleconaril has been shown to have activity against a number of enteroviruses[52][53][54][55][56] but has not been approved by the FDA.

Treatment usually involves supporting the immune response particularly in those with documented immune dysfunction. Dr. Chia treats his patients with enteroviral infection with Equilibrant, gammaglobulin and interferon.[57]

Talks and interviews

Learn more

- Enteroviruses: Health, Learn, Live

- Enterovirus Foundation: Signs and Symptoms

- Enteroviruses (Medscape article)

- Non-Polio Enterovirus (CDC article)

- Dr John Chia, International Symposium on Viruses In CFS 2008, The Role of Enterovirus in ME/CFS

- Dr John Chia, State of Knowledge Workshop on ME/CFS Research 2011 (Day 1) Part 1

- Dr John Chia, State of Knowledge Workshop on ME/CFS Research 2011 (Day 1) Part 2

- Dr John Chia, Invest in ME International ME Conference, London 2009: Diagnosis and Treatment of ME/CFS Associated With Chronic Enterovirus Infection

- Dr John Chia, Invest in ME International ME Conference, London 2010: Enterovirus Infection in ME/CFS

- Dr John Chia, Invest in ME International ME Conference, London 2011: Clinical and Research Experience of Enteroviral Involvement in ME/CFS

- Dr John Chia, Invest in ME International ME Conference, London 2015: Enteroviruses and ME/CFS: An Update on Pathogenesis

- ME/CFS and Polio, chapter from book "ME: The New Plague", Jane Colby.[58]

- The Enterovirus Theory of Disease Etiology in ME/CFS: A Critical Review, paper by Adam O'Neal and Maureen R. Hanson, 2021.

- The viral origin of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, paper by Maureen R. Hanson, 2023.

See also

- Coxsackie B

- Enteroviral infection hypothesis

- Viral testing in ME/CFS

- Irving Spurr

- James Mowbray

- John Chia

- John Richardson

- List of enterovirus infection studies

- Non-cytolytic enterovirus

- Post-mortem brain studies

References

- ↑ Yin-Murphy, Marguerite; Almond, Jeffrey W. (1996). Baron, Samuel (ed.). Picornaviruses. Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. PMID 21413259.

- ↑ Alsina-Gibert, Mercè. "Dermatologic Manifestations of Enteroviral Infections (Medscape article)". Medscape.

Enteroviruses spread from person to person by either oral-oral or fecal-oral routes.

- ↑ "Non-Polio Enterovirus". CDC Website.

Non-Polio Enterovirus. Non-polio enteroviruses are very common. They cause about 10 to 15 million infections and tens of thousands of hospitalizations each year in the United States. Most people who get infected with these viruses do not get sick or they only have mild illness, like the common cold.

- ↑ Schwartz, Robert A. "Enteroviruses (Medscape article)". Medscape.

More than 90% of infections caused by nonpolio entero viruses are asymptomatic or result only in an undifferentiated febrile illness.

- ↑ Choudhary, Madhu Chhanda. "Echovirus Infection". Medscape.

More than 90% of echoviral infections are asymptomatic.

- ↑ Poliovirus - Virology Blog

- ↑ Koundouris, A (May 2000). "Poliovirus Induces an Early Impairment of Mitochondrial Function by Inhibiting Succinate Dehydrogenase Activity". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 271: 610–4.

- ↑ Landay, AL (September 1991). "Chronic fatigue syndrome: clinical condition associated with immune activation". Lancet.

- ↑ Chia, John (November 2005). "The role of enterovirus in chronic fatigue syndrome". Journal of Clinical Pathology.

- ↑ Fegan, KG; Behan, PO; Bell, EJ (June 1, 1983), "Myalgic encephalomyelitis — report of an epidemic", J R Coll Gen Pract, 33 (251): 335–337, PMID 6310104

- ↑ Calder, BD; Warnock, PJ (January 1984), "Coxsackie B infection in a Scottish general practice", Jrnl Royal Coll Gen Pract, 34 (258): 15–19, PMID 6319691

- ↑ Yousef, G.E. (January 1988). "Chronic Enterovirus Infection In Patients With Postviral Fatigue Synfrome". The Lancet.

- ↑ Nairn, C (August 1995). "Comparison of coxsackie B neutralisation and enteroviral PCR in chronic fatigue patients". Journal of Medical Virology.

- ↑ Chia, John (November 2005). "The role of enterovirus in chronic fatigue syndrome". Journal of Clinical Pathology.

- ↑ Gow, JW. "Enteroviral RNA sequences detected by polymerase chain reaction in muscle of patients with postviral fatigue syndrome". British Medical Journal.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control (August 12, 2020). "Non-Polio Enterovirus | About EV-D68 | Enterovirus D68". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ↑ Chia, John (2015). "Enteroviruses and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis / Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: An Update on Pathogenesis. Presentation at the Invest in ME International ME Conference, London 2015". 1:24.

- ↑ "Symptoms and Signs of an Enterovirus Infection". Enterovirus Foundation.

- ↑ "Non-Polio Enterovirus: Symptoms". CDC Website.

- ↑ Chia, John (2010). "Enterovirus Infection in ME/CFS. Presentation at the Invest in ME International ME Conference, London 2010".

Enterovirus is the greatest mimicker of chickenpox. If the patient already had chickenpox before and they then develop flu-like illness with chickenpox-like rashes that's enterovirus until proven otherwise. But the rash could look like measles, German measles, it could look like hives.

- ↑ Chia, John (2011). "Clinical and Research Experience of Enteroviral Involvement in ME/CFS. Presentation at the Invest in ME International ME Conference, London 2011".

Only one group of viruses that routinely will go to the muscles heart and the brain, and that's enteroviruses.

- ↑ Chia, John (2015). "Enteroviruses and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis / Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: An Update on Pathogenesis. Presentation at the Invest in ME International ME Conference, London 2015".

These viruses can then spread to the central nervous system, the heart, and also muscles. As a group these are viruses are actually the only virus that can actually to go to all three sites, OK. The other viruses can go to one or two and others.

- ↑ "Coxsackievirus — Material Safety Data Sheet - Infectious Substances".

- ↑ "Pathogen Safety Data Sheets: Infectious Substances – Echovirus".

- ↑ Muller, Martha L. "Coxsackieviruses Clinical Presentation (Medscape article)". Medscape.

Coxsackievirus B (serotypes 2-5) and echoviruses account for more than 90% of viral causes of aseptic meningitis.

- ↑ Andréoletti, Laurent; Ventéo, Lydie; Douche-Aourik, Fatima; Canas, Frédéric; Lorin de la Grandmaison, Geoffroy; Jacques, Jérôme; Moret, Hélène; Jovenin, Nicolas; Mosnier, Jean-François (December 4, 2007). "Active Coxsackieviral B infection is associated with disruption of dystrophin in endomyocardial tissue of patients who died suddenly of acute myocardial infarction". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 50 (23): 2207–2214. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.080. ISSN 1558-3597. PMID 18061067.

- ↑ Nicholls, A.C.; Thomas, M. (April 23, 1977). "Coxsackie virus infection in acute myocardial infarction". Lancet (London, England). 1 (8017): 883–884. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 67289.

- ↑ Kim, K.-S.; Tracy, S.; Tapprich, W.; Bailey, J.; Lee, C.-K.; Kim, K.; Barry, W.H.; Chapman, N.M. (June 2005). "5'-Terminal deletions occur in coxsackievirus B3 during replication in murine hearts and cardiac myocyte cultures and correlate with encapsidation of negative-strand viral RNA". Journal of Virology. 79 (11): 7024–7041. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.11.7024-7041.2005. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 1112132. PMID 15890942.

Picornavirus infections are generally considered to be acute and cleared rapidly by the host adaptive immune response.

- ↑ Flynn, Claudia T.; Kimura, Taishi; Frimpong-Boateng, Kwesi; Harkins, Stephanie; Whitton, J. Lindsay (December 2017). "Immunological and pathological consequences of coxsackievirus RNA persistence in the heart". Virology. 512: 104–112. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2017.09.017. ISSN 0042-6822. PMC 5653433. PMID 28950225.

until relatively recently, enteroviruses were thought to cause only acute infections, and to be completely eradicated with ~ 2 weeks of the primary infection.

- ↑ Chia, John (2015). "Enteroviruses and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis / Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: An Update on Pathogenesis. Presentation at the Invest in ME International ME Conference, London 2015".

- ↑ "Enterovirus Foundation — Diagnose & Treat".

- ↑ Chia, John (2009). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis / Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Associated with Chronic Enterovirus Infection. Presentation at the Invest in ME International ME Conference, London 2009".

The typical antibody that the laboratory would do is called the complement fixation test, which is neither sensitive nor specific. That means if you get a positive test, it's worthless. And if you get a negative test, it's worthless. Well that's wonderful.

- ↑ Chia, John. "Dr John Chia: Enterovirus Infection in ME/CFS. Presentation at the Invest in ME International ME Conference, London 2010".

Here is a young lady's abdomen: you can notice that there's some viral distention, the patient consistently complaining of epigastric pain, nausea, right lower quadrant pain, and left lower quadrant pain. And when I pushed on it, on these X's, can definitely tell me, the tenderness. This is actually a fairly reliable sign to detect enterovirus infection of the abdomen.

- ↑ Chia, John. "Clinical and Research Experience of Enteroviral Involvement in ME/CFS. Presentation at the Invest in ME International ME Conference, London 2011".

This is actually a very helpful clinical finding. As you know in the definition of ME/CFS, there is sore throat, and ... ... ok, but there is very little attention to the abdominal symptoms, which most patients actually have. Patients often complain of pain up here, here's the rib cage, end of the rib cage, this is where the stomach is. They oftentimes have pain in the right lower quadrant, roughly where the appendix is, and that's the end of the terminal ileum, as I have shown you in the case before. They oftentimes have tenderness in the left lower quadrant, that either the small bowel here, or the colon, which we are actually able to show proteins or viral RNA in these areas.

- ↑ Parish, JG (1978). "Early outbreaks of 'epidemic neuromyasthenia'". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 54: 711–7.

- ↑ Cunningham, L.; Bowles, N.E.; Lane, R.J.; Dubowitz, V.; Archard, L.C. (June 1990). "Persistence of enteroviral RNA in chronic fatigue syndrome is associated with the abnormal production of equal amounts of positive and negative strands of enteroviral RNA". The Journal of General Virology. 71 (Pt 6): 1399–1402. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-71-6-1399. ISSN 0022-1317. PMID 2161907.

- ↑ Fegan, KG; Behan, PO; Bell, EJ (June 1, 1983), "Myalgic encephalomyelitis — report of an epidemic", J R Coll Gen Pract, 33 (251): 335–337, PMID 6310104

- ↑ Calder, BD; Warnock, PJ (January 1984), "Coxsackie B infection in a Scottish general practice", Jrnl Royal Coll Gen Pract, 34 (258): 15–19, PMID 6319691

- ↑ Dowsett, EG; Ramsay, AM; McCartney, RA; Bell, EJ (July 1, 1990), "Myalgic encephalomyelitis--a persistent enteroviral infection?", Postgraduate Medical Journal, 66 (777): 526–530, doi:10.1136/pgmj.66.777.526, PMID 2170962

- ↑ Yousef, G.E. (January 1988). "CHRONIC ENTEROVIRUS INFECTION IN PATIENTS WITH POSTVIRAL FATIGUE SYNDROME". The Lancet.

- ↑ Miller, N A (1991). "Antibody to Coxsackie B virus in diagnosing postviral fatigue syndrome". The British Medical Journal.

- ↑ Nairn, C (August 1995). "Comparison of coxsackie B neutralisation and enteroviral PCR in chronic fatigue patients". Journal of Medical Virology.

- ↑ Chia, John (November 2005). "The role of enterovirus in chronic fatigue syndrome". Journal of Clinical Pathology.

- ↑ Gow, JW. "Enteroviral RNA sequences detected by polymerase chain reaction in muscle of patients with postviral fatigue syndrome". British Medical Journal.

- ↑ Gow, JW (1994). "Studies on enterovirus in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome". Clin Infect Dis. 18: S126-9.

- ↑ Chia, JKS; Chia, AY (January 1, 2008), "Chronic fatigue syndrome is associated with chronic enterovirus infection of the stomach", Journal of Clinical Pathology, 61 (1): 43–48, doi:10.1136/jcp.2007.050054, PMID 17872383

- ↑ Gamble, D.R.; Taylor, K.W.; Cumming, H. (November 3, 1973). "Coxsackie Viruses and Diabetes Mellitus". British Medical Journal. 4 (5887): 260–262. ISSN 0007-1447. PMC 1587352. PMID 4753237.

- ↑ Ylipaasto, P.; Klingel, K.; Lindberg, A.M.; Otonkoski, T.; Kandolf, R.; Hovi, T.; Roivainen, M. (February 1, 2004). "Enterovirus infection in human pancreatic islet cells, islet tropism in vivo and receptor involvement in cultured islet beta cells". Diabetologia. 47 (2): 225–239. doi:10.1007/s00125-003-1297-z. ISSN 0012-186X.

- ↑ Bason, Caterina; Lorini, Renata; Lunardi, Claudio; Dolcino, Marzia; Giannattasio, Alessandro; d’Annunzio, Giuseppe; Rigo, Antonella; Pedemonte, Nicoletta; Corrocher, Roberto (February 28, 2013). "In Type 1 Diabetes a Subset of Anti-Coxsackievirus B4 Antibodies Recognize Autoantigens and Induce Apoptosis of Pancreatic Beta Cells". PLOS ONE. 8 (2): e57729. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057729. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3585221. PMID 23469060.

- ↑ http://www.pnas.org/content/104/12/5115.full

- ↑ Barkin, JA; Czul, F; Barkin, JS; Klimas, NG; Rey, IR; Moshiree, B (2016), "Gastric Enterovirus Infection: A Possible Causative Etiology of Gastroparesis", Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 61 (8): 2344-50, doi:10.1007/s10620-016-4227-x, PMID 27344315

- ↑ Rotbart, HA; Webster, AD (January 15, 2001), "Treatment of Potentially Life-Threatening Enterovirus Infections with Pleconaril", Clinical Infectious Diseases, 32 (2): 228–235, doi:10.1086/318452, PMID 11170912

- ↑ Pevear, Daniel C; Tull, Tina M; Seipel, Martin E; Groarke, James M (September 1, 1999), "Activity of Pleconaril against Enteroviruses", Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 43 (9): 2109–2115, PMID 10471549

- ↑ Bauer, Sofia; Gottesman, Giora; Sirota, Lea; Litmanovitz, Ita; Ashkenazi, Shay; Levi, Itzhak (July 23, 2002), "Severe Coxsackie virus B infection in preterm newborns treated with pleconaril", European Journal of Pediatrics, 161 (9): 491–493, doi:10.1007/s00431-002-0929-5

- ↑ Groarke, James M; Pevear, Daniel C (June 1, 1999), "Attenuated Virulence of Pleconaril-Resistant Coxsackievirus B3 Variants", Journal of Infectious Diseases, 179 (6): 1538–1541, doi:10.1086/314758, PMID 10228078

- ↑ Abzug, Mark J; Michaels, Marian G; Wald, Ellen; Jacobs, Richard F; Romero, José R; Sánchez, Pablo J; Wilson, Gregory; Krogstad, Paul; Storch, Gregory A; Lawrence, Robert; Shelton, Mark; Palmer, April; Robinson, Joan; Dennehy, Penelope; Sood, Sunil K; Cloud, Gretchen; Jester, Penelope; Acosta, Edward P; Whitley, Richard; Kimberlin, David; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Collaborative Antiviral Study Group (March 2016), "A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Pleconaril for the Treatment of Neonates With Enterovirus Sepsis", Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, 5 (1): 53–62, doi:10.1093/jpids/piv015, PMID 26407253

- ↑ "Treatments for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome", EvMed Research (webpage)

- ↑ Colby, Jane (1996). "Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A polio by another name". ME: The New Plague.