1953 Maryland outbreak

1953 Maryland outbreak: In July, 1953, a sudden outbreak of a polio-like infection occurred in the student nurses at Chestnut Lodge Hospital, a private, psychiatric hospital in Rockville, Maryland, near Washington, DC.[1]

The Montgomery County Health Department, the Maryland State Health Department, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Georgetown University School of Medicine were involved in deciphering the outbreak.

Symptoms

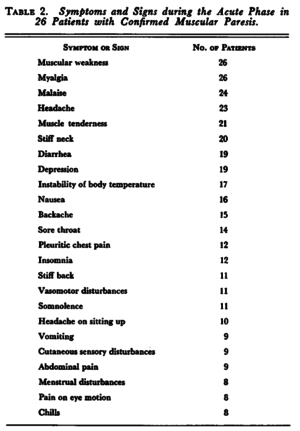

The investigators authored an article for the New England Journal of Medicine and noted the following core symptoms[1]:

- localized muscular weakness (paresis)

- stiffness of the neck and back

- headache

- diarrhea

- temperature elevation and instability of body temperature

The outbreak was deemed to resemble other outbreaks of poliomyelitis-like illnesses in hospitals around the same time, including the Los Angeles County Hospital in 1934. Epidemic neuromyasthenia became the final diagnosis.[1]

Often a minor illness characterized by flu-like malaise, achiness and low-grade fever proceeded by several days to up to two weeks the development of a full-blown symptom complex (i.e., involving muscle weakness and partial paralysis). If the prodromal period persisted, symptoms might include diarrhea, nausea and vomiting and in some cases, severe respiratory illnesses.[1]

Additional symptoms included sore throat, postural headache, abdominal pain, menstrual irregularities, and pain on eye motion.[1]

Findings

- Lumbar punctures were done on 25 of the cases and all 25 were negative for cerebrospinal fluid involvement. Eight lumbar punctures were repeated and all of those were negative, also.[2]

- Muscle weakness was confirmed in half of cases via quantitative muscular-testing procedures[1]

- From several of the patients, the Bethesda-Ballerup paracolon organism was isolated. It was believed that this organism may have triggered the disease in the same manner as an infection of poliomyelitis virus precipitated other early epidemics.[3]

- Hemoglobin determinations, erythrocyte counts, sedimentation rates and urinalyses were within normal limits

- Tendency toward lymphocytosis in the acute phase

- All infectious disease testing (including tests for a range of enteroviruses) was negative

Epidemiology

Fifty cases were documented: 48 females and 2 males, of which 47 of the cases were in the student nurse population.[2] A second outbreak occurred two and a half months after the first major group of cases, during which 7 cases appeared in a newly introduced student-nurse population. No toxic agent was found.

Course & prognosis

Patients often experienced an "early and misleading improvement"[1] only to enter a chronic state of "prolonged debility," suffering relapses with exertion, damp and cold weather or onset of menstrual periods.

Controversy

In 1970, this outbreak was one of fifteen mentioned in a paper by psychiatrists Colin McEvedy and A. W. Beard, who wanted to rename all fifteen outbreaks as mass hysteria or myalgia nervosa.[2] The psychiatrists were criticized by patients and researchers, such as Dr. Melvin Ramsay who was directly involved in the 1955 Royal Free Hospital outbreak. McEvedy admitted to Dr. Byron Hyde, when invited to discuss his theory, that he did not examine any patients and undertook only the most cursory examination of medical records.[4]

In 1994, Nathaniel C. Briggs and Paul H. Levine, from the Viral Epidemiology Branch, Epidemiology and Biostatistics Program of the National Institutes of Health, wrote a review comparing twelve outbreaks referred to as chronic fatigue syndrome, epidemic neuromyasthenia, and myalgic encephalomyelitis. They grouped the outbreaks into four levels of increasing neurological involvement, ranked I-IV. The 1953 Maryland outbreak was rated as level III, which meant that they found "objective paresis with cutaneous sensory as well as affective and cognitive neuropsychological changes." The researchers noted that: "'unusual fatigability' was a cardinal symptom. Twelve (46%) of 26 patients reexamined 3-5 months after onset were symptomatic and 'several had to be on part-time duty with periods of daytime bed rest'" and patients experienced "frequent recrudescensces [increased severity of a disease after a remission] particularly associated with exertion."[5]

See also

- Epidemic myalgic encephalomyelitis

- List of myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome outbreaks

Learn more

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Shelokov, Alexis; Habel, Karl; Verder, Elizabeth; Welsh, William (August 1957). "Epidemic Neuromyasthenia — An Outbreak of Poliomyelitis-like Illness in Student Nurses". New England Journal of Medicine (257): 345-355. doi:10.1056/NEJM195708222570801.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 McEvedy, Colin; Beard, A.W. (1970). "Concept of Benign Myalgic Encephalomyelitis". British Medical Journal. 1970 (1): 11-15. PMID 5411596.

- ↑ Parish, J.G. (November 1978). "Early outbreaks of 'epidemic neuromyasthenia'". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 54 (637): 711-717. PMID 370810.

- ↑ Hooper, Malcolm (May 2007). "Myalgic encephalomyelitis: a review with emphasis on key findings in biomedical research". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 60 (5): 466–471. doi:10.1136/jcp.2006.042408.

- ↑ Briggs, Nathaniel C.; Levine, Paul H. (1994). "A Comparative Review of Systemic and Neurological Symptomatology in 12 Outbreaks Collectively Described as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Epidemic Neuromyasthenia, and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1994 (Suppl 1): S32-42. doi:10.1093/clinids/18.Supplement_1.S32. PMID 8148451.