Tethered cord syndrome

This article needs cleanup to meet MEpedia's guidelines. The reason given is: Image copyright issues (5 August, 2018) |

Tethered cord syndrome is a neurological disorder caused by tissue attachments that limit the movement of the spinal cord within the spinal column. It can be congenital or acquired and appear in childhood or adulthood. It is considered progressive.[1]

It causes spinal cord hypoperfusion, electrophysical changes and metabolic changes, including impaired glucose metabolism.[2][3][4]

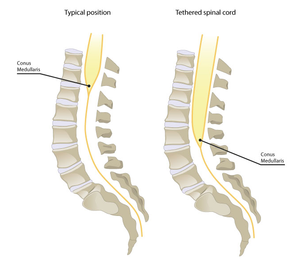

There are a range of conditions associated with tethered cord. The most dramatic is spina bifida, where the spinal cord does not complete its development and is visible on the outside of the body.[5] In a frank tethered cord, the cord is not visible on the outside of the body, but has not fully developed and is anchored to the structures inside the spinal column. (Tethered cord is analogous to a tongue tie, where a thick web attaches the tongue to the base of the mouth and impedes the free movement of the tongue.) In some cases, the base of the spinal cord, the conus, is much lower than it should be and is below the level of the first lumbar vertebra; this is how neurosurgeons typically diagnose tethered cord. However, the cord can still be tethered without this radiological finding - this is referred to as an occult or hidden tethered cord, or a tight filum.[6]

As with craniocervical instability, there have also been anecdotal reports of patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) who were later diagnosed with tethered cord, although no scientific publication on this subject exists.[7][8][9]

Onset[edit | edit source]

Some researchers, noting that less severe spinal cord traction may remain asymptomatic in childhood[10], hypothesize that the age of symptom onset is related to the amount of cord stretch. Factors in adult onset tethered cord syndrome include: transient stretching of the spine, mechanical constriction/narrowing of the spinal canal, and spinal trauma, all in the presence of an already tightly tethered conus medullaris, such as might occur during natural childbirth or in an automobile accident.[10]

Signs and Symptoms[edit | edit source]

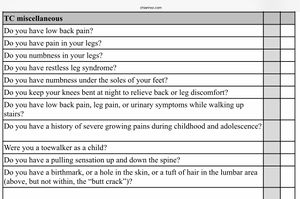

Symptoms[6][11][12][13][14][15][16] of tethered cord syndrome may include:

- Leg pain (often migratory/traveling), weakness, and/or numbness

- Neck pain

- Suboccipital pain/pressure

- Lower back pain

- Pulling sensation (on brain or upper spine, from below)

- Neck or spine stiffness

- Restless legs

- Rectal pain

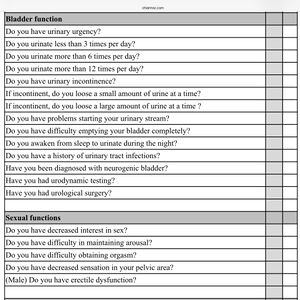

- Urinary urgency or incontinence

- Frequent urination (*most people urinate 6-7 times in a 24 hour period)

- Urinary retention / difficulty emptying bladder completely

- Bowel dysfunction

- Constipation

- Numbness under soles of feet

- Falling/tripping/clumsiness

- Decreased sensation or and/or hypersensitivity in feet

- Decreased sensation and/or hypersensitivity in genitals

- Decreased interest in sex

- Difficulty maintaining arousal or achieving orgasm

- Seizure

- Tinnitus

Signs of tethered cord syndrome may include:

- Sacral dimple (see 10A.2)

- Birthmark, hole in skin, or tuft of hair in lumbar area

- Scoliosis

- Kyphosis

- Hip/knee subluxations

- Sacral pain

- Foot/ankle deformities

- Asymmetry in neurological deficits

- Hyperreflexia/clonus

- Tremors

- Light touch deficit

- Curling toes

Symptoms tend to increase when:

- Walking or running

- Walking on heels

- Walking up stairs

- Laying completely flat

Symptoms tend to decrease when:

- Walking on toes

- Laying with knees bent

- Avoiding walking long distances

- Avoiding standing still

Childhood indictors (relevant for children as well as adults who may have mild and largely assymptomatic prior to illness onset):

- Cutaneous signs at birth, e.g., sacral dimple, birth mark, hole, tuft of hair in lumbar area

- Late bedwetting

- Growing pains

- Walking on toes as a child (and/or prefering high heels or wedge shoes as an adult)

- Difficulty running

- ”Clumsiness”

- Thoracic kyphosis (hunched shoulders) after puberty/with growth in height

- Scoliosis

Other possible indicators:

- Frequent urinary tract infections

- Interstitial cystisis

- Pelvic floor dysfunction

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Imaging[edit | edit source]

If a tethered cord is suspected, one or more tests may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. The most common is a lumbar MRI, but a myleogram, CT scan, or ultrasound may also aid in diagnosis[17]

Occult tethered cord syndrome[edit | edit source]

Occult tethered cord syndrome describes patients with the signs and symptoms of tethered cord syndrome but who have normal neuroimaging. These cases are often diagnosed via a urodynamics study, which can reveal neurogenic bladder.[18]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

There is no standard technique in the surgical treatment of TCS. Generally, the lamina is removed, anywhere from L2 to S1, a durotomy is made, and electrical stimulation is used to confirm the absence of any nerve roots which may be associated with the filum. Finally, a microsurgical resection of the filum terminale (usually a 10 mm segment for pathology) is performed. The filum tends to be taut, and to briskly retract upon sectioning. However, findings are variable, and there is no evidence to suggest that the intraoperative findings predict or correlate with the surgical outcome and severity of the TCS. In some cases, it may be necessary to perform a lumbar stabilization across the motion segment in which the filum was sectioned. The resected filum should be sent for histopathological evaluation.[19]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Metabolism[edit | edit source]

Tethered cord, a form of mechanical neural strain, is associated with impaired glucose metabolism in spinal cord tissue,[2] changes in the reduction/oxidation ratio of cytochrome oxidase.[20] and reduced ATP production.[21] Energy loss due to neural membrane stretching contributes to leakage of sodium, potassium and calcium.[22]

A study of energy cost of walking in adolescents with tethered cord, as measured by oxygen uptake, found that “energy cost per metre during walking at preferred speed and physical strain were higher than in peers without disability.”[23]

Blood flow[edit | edit source]

People with tethered cord syndrome have reduced blood flow to the spinal cord.[2]

“Traction on the caudal cord results in decreased blood flow causing metabolic derangements that culminate in motor, sensory, and urinary neurological deficits. The untethering operation restores blood flow and reverses the clinical picture in most symptomatic cases.”[24]

In a study of five children undergoing surgery for tethered cord syndrome group, spinal cord blood flow prior to untethering was a mean of 12.6 ml/min per 100 g of tissue. It increased in all cases after release to a mean of 29.4 ml/min per 100 g of tissue.[25]

Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

See also[edit | edit source]

Learn more[edit | edit source]

- “Tethered Cord Syndrome,” Journal of Neurosurgery, 2009.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ "Tethered Spinal Cord Syndrome Information Page | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". ninds.nih.gov. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Colohan, Austin R. T.; Zouros, Alexander; Siddiqi, Javed; Yamada, Shoko M.; Yamada, Brian S.; Pezeshkpour, Gholam; Won, Daniel J.; Yamada, Shokei (August 1, 2007). "Pathophysiology of tethered cord syndrome and similar complex disorders". Neurosurgical Focus. 23 (2): 1–10. doi:10.3171/FOC-07/08/E6. ISSN 1092-0684.

- ↑ Colohan, Austin R. T.; Yamada, Shokei (January 1, 2009). "Tethered Cord Syndrome". Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine. 10 (1): 79–80. doi:10.3171/2008.10.SPI15714L.

- ↑ Sullivan, Stephen; Park, Paul; Stetler, William R. (July 1, 2010). "Pathophysiology of adult tethered cord syndrome: review of the literature". Neurosurgical Focus. 29 (1): E2. doi:10.3171/2010.3.FOCUS1080. ISSN 1092-0684.

- ↑ "Spina Bifida Fact Sheet | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". ninds.nih.gov. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "3rd CSF Disorders Symposium: The Occult Tethered Cord Syndrome | CSF". csfinfo.org. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- ↑ "Have you ruled out Chiari as a cause of your CFS". Phoenix Rising.

- ↑ Brea, Jennifer (June 6, 2019). "CCI + Tethered cord series". Medium. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ↑ "Craniocervical instability, Atlantoaxial Instability, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, ME, CFS". MEchanical Basis. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Wilberger, James E.; Pang, Dachling (July 1, 1982). "Tethered cord syndrome in adults". Journal of Neurosurgery. 57 (1): 32–47. doi:10.3171/jns.1982.57.1.0032.

- ↑ Wilberger, James E.; Pang, Dachling (July 1, 1982). "Tethered cord syndrome in adults". Journal of Neurosurgery. 57 (1): 32–47. doi:10.3171/jns.1982.57.1.0032.

- ↑ "Tethered Spinal Cord". Seattle Children’s Hospital. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- ↑ Gupta, S. K; Khosla, V. K; Sharma, B. S; Mathuriya, S. N; Pathak, A; Tewari, M. K (October 1, 1999). "Tethered cord syndrome in adults". Surgical Neurology. 52 (4): 362–370. doi:10.1016/S0090-3019(99)00121-4. ISSN 0090-3019.

- ↑ Saita, Kazuo; Yamaguchi, Takehiko; Chikuda, Hirotaka; Akiyama, Toru; Kanda, Shotaro (2015). "An Unusual Presentation of Adult Tethered Cord Syndrome Associated with Severe Chest and Upper Back Pain". Case Reports in Orthopedics. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- ↑ "Tethered Spinal Cord Syndrome – Causes, Diagnosis and Treatments". aans.org. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- ↑ 2019 ASAP Conference: Tethered Cord Syndrome, P Klinge, MD, PhD, retrieved August 11, 2021

- ↑ "Tethered Spinal Cord Syndrome – Causes, Diagnosis and Treatments". aans.org. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- ↑ Metcalfe, P. D.; Luerssen, T.G.; King, S.J.; Kaefer, M.; Meldrum, K.K.; Cain, M.P.; Rink, R.C.; Casale, A.J. (October 2006). "Treatment of the occult tethered spinal cord for neuropathic bladder: results of sectioning the filum terminale". The Journal of Urology. 176 (4 Pt 2): 1826–1829, discussion 1830. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2006.04.090. ISSN 0022-5347. PMID 16945660.

- ↑ Henderson, Fraser C.; Austin, Claudiu; Benzel, Edward; Bolognese, Paolo; Ellenbogen, Richard; Francomano, Clair A.; Ireton, Candace; Klinge, Petra; Koby, Myles (2017). "Neurological and spinal manifestations of the Ehlers–Danlos syndromes". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics. 175 (1): 195–211. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31549. ISSN 1552-4876.

- ↑ Yamada, Shoko M.; Won, Daniel J.; Yamada, Shokei (February 1, 2004). "Pathophysiology of tethered cord syndrome: correlation with symptomatology". Neurosurgical Focus. 16 (2): 1–5. doi:10.3171/foc.2004.16.2.7. ISSN 1092-0684.

- ↑ Sullivan, Stephen; Park, Paul; Stetler, William R. (July 1, 2010). "Pathophysiology of adult tethered cord syndrome: review of the literature". Neurosurgical Focus. 29 (1): E2. doi:10.3171/2010.3.FOCUS1080. ISSN 1092-0684.

- ↑ Yamada, Shokei; Iacono, Robert P.; Andrade, Terry; Mandybur, George; Yamada, Brian S. (April 1, 1995). "Pathophysiology of Tethered Cord Syndrome". Neurosurgery Clinics of North America. Spinal Dysraphism. 6 (2): 311–323. doi:10.1016/S1042-3680(18)30465-0. ISSN 1042-3680.

- ↑ Bruinings, A. L.; Berg‐Emons, H. J. G. Van Den; Buffart, L.M.; Heijden‐Maessen, H. C.M. Van Der; Roebroeck, M.E.; Stam, H.J. (2007). "Energy cost and physical strain of daily activities in adolescents and young adults with myelomeningocele". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 49 (9): 672–677. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00672.x. ISSN 1469-8749.

- ↑ Rekate, Harold L.; Theodore, Nicholas; Kalani, M. Yashar; Filippidis, Aristotelis S. (July 1, 2010). "Spinal cord traction, vascular compromise, hypoxia, and metabolic derangements in the pathophysiology of tethered cord syndrome". Neurosurgical Focus. 29 (1): E9. doi:10.3171/2010.3.FOCUS1085. ISSN 1092-0684.

- ↑ Danto, Joseph; Greenberg, Burt M.; Rosenthal, Alan D.; Schneider, Steven J. (February 1, 1993). "A Preliminary Report on the Use of Laser-Doppler Flowmetry during Tethered Spinal Cord Release". Neurosurgery. 32 (2): 214–218. doi:10.1227/00006123-199302000-00010. ISSN 0148-396X.

- ↑ Mantia, Roberto; Di Gesù, Marco; Vetro, Angelo; Mantia, Fabrizio; Palma, Sebastiano; Iovane, Angelo (March 27, 2015). "Shortness of filum terminale represents an anatomical specific feature in fibromyalgia: a nuclear magnetic resonance and clinical study". Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. 5 (1): 33–37. ISSN 2240-4554. PMC 4396674. PMID 25878985.