Nutcracker phenomenon

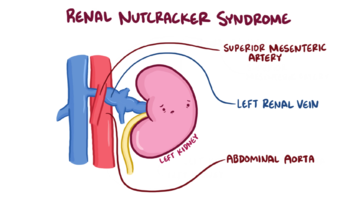

Nutcracker phenomenon, also known as left renal vein entrapment, refers to compression of the left renal vein, most commonly between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery, with impaired blood outflow often accompanied by distention of the distal portion of the vein.[1] Normally, the left renal vein brings blood out of the left kidney and into the inferior vena cava, the body’s largest vein. Compression of the left renal vein can cause blood to flow backward into other nearby veins.

The term nutcracker syndrome most often refers to the classic symptoms that can arise from the nutcracker phenomenon, e.g. hematuria, abdominal pain (classically left flank or pelvic pain) and orthostatic proteinuria.[1][2][3] Some patients with nutcracker phenomenon don't have all of these classic symptoms though (hematuria, for example, is obligatory in nutcracker syndrome[2]), but still suffers from other symptoms arising from this vein compression disorder.[2][4][5] Hence, both the terms nutcracker syndrome and nutcracker phenomenon can be used to describe symptomatic left renal vein entrapment. There's a wide spectrum of clinical presentations and diagnostic criteria are not well defined, which frequently results in delayed or incorrect diagnosis.[1]

Nutcracker phenomenon has been linked to CFS and dysautonomia in several medical journal articles, both in pediatric and adult patients. Theories regarding the various ways in which nutcracker phenomenon can cause these symptoms include:

- severe congestion in the kidney may cause the expansion of the renal venous bed, which would affect the renin-angiotensin system.[5]

- severe congestion in the adrenal medulla, which is innervated by sympathetic nerves, may disturb a complex set of central neural connections controlling the sympathoadrenal system.[5]

- overproduction or night retention of catecholamines.[5]

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms and severity of renal nutcracker phenomenon can vary from person to person.[6] Some people may not have any symptoms (especially children), while others have severe and persistent symptoms.[6] Symptoms are often worsened by physical activity.[6]

Signs and symptoms may include:[6]

- Blood in the urine (hematuria) which can occasionally cause anemia requiring blood transfusions.

- Abdominal or flank pain that may radiate to the thigh and buttock. Pain may be worsened by sitting, standing, walking, or riding in a vehicle that shakes.

- Varicocele in men - almost always occurring on the left side.

- Chronic fatigue syndrome and fatigue symptoms.

- Pelvic congestion syndrome, causing symptoms such as chronic pelvic pain, pain during intercourse, painful or difficult urination, painful menstrual cramps during periods, and polycystic ovaries.

- Orthostatic proteinuria.

- Orthostatic intolerance (feeling light-headed or having palpitations when standing upright).

- Tachycardia[7][5]

- Headache[8][4]

- Syncope[4][9]

- Nausea[4][9]

ME/CFS & dysautonomic comorbidities

Hammami et al. (2017) published a case-study of a young man with a seven-year history of chronic fatigue syndrome, chronic pelvic pain syndrome, and vague abdominal pain. He also had orthostatic hypotension, “slowed thinking”, an inability to exercise without feeling lightheaded, and he showed a possible tachycardic response during a tilt table test. He was found to have imaging characteristics consistent with nutcracker phenomenon. He underwent surgery to insert a left renal vein stent, and his symptoms resolved soon after the intervention.[10]

Takahashi, Ohta et al. (2000) describes 9 children with CFS or idiopathic chronic fatigue who were often absent from school with suspected psychosomatic disorders.[11] The children had a broad range of symptoms including chronic fatigue, headache, abdominal pain, unrefreshing sleep, muscle pain, joint pain, sore throat, low-grade fever, afebrile chills in hot summer, depression, postural tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, dizziness, lightheadedness and other autonomic dysfunction symptoms, some reported fibromyalgia-type pain, and some reported proteinuria.[12][5][11]

Takahashi, Ohta et al. investigated the cause of the orthostatic proteinuria and found that the children had severe nutcracker phenomenon (NC). Further investigation revealed that nutcracker phenomenon was present in all 9 children with CFS, including those without orthostatic proteinuria.[11] They concluded:

- "Their symptoms filled the criteria of chronic fatigue syndrome or idiopathic chronic fatigue (CFS/CF). An association between severe NC and autonomic dysfunction symptoms in children with CFS/CF has been presented."[11]

Takahashi, Ohta et al. point out that in their experience the classic symptom of renal bleeding (presenting as micro or macro-hematuria) was not present in children with CFS-associated nutcracker phenomenon.[5][11] Takahashi, Ohta et al. suggested possible ways in which nutcracker phenomenon might affect autonomic function:

- severe congestion in the kidney may cause the expansion of the renal venous bed, which would affect the renin-angiotensin system.

- severe congestion in the adrenal medulla, which is innervated by sympathetic nerves, may disturb a complex set of central neural connections controlling the sympathoadrenal system.

- alternatively, overproduction or night retention of catecholamines might be responsible for the various symptoms of pediatric chronic fatigue syndrome.[11][12][5]

Takahashi et al. (2000) describes a 13-year-old girl who suffered from orthostatic hypotension, tachycardia and chronic fatigue syndrome.[7] The patient was also diagnosed with nutcracker phenomenon, and was successfully treated with transluminal balloon angioplasty of the compressed left renal vein between the aorta and superior mesenteric artery. Both her dysautonomia and CFS improved after the intervention.[12][7]

Dysautonomia

Takahashi et al. (2005) tested 93 pediatric patients for nutcracker phenomenon (56 with idiopathic renal bleeding, 14 with massive orthostatic proteinuria and 23 with severe orthostatic intolerance). Left renal vein occlusion (nutcracker phenomenon) was observed in 70% of the patients with severe orthostatic intolerance, and in contrast in 18% and 14% for idiopathic renal bleeding and massive orthostatic proteinuria, respectively.[13]

Takemura et al. (2000) published a paper describing four adolescents diagnosed with nutcracker syndrome. Three of these patients had previously been diagnosed with orthostatic disturbance and suffered from various symptoms including fainting, tachycardia, headache and abdominal pain.[8]

A case-report from Daily et al. (2012) describes a 19-year-old woman diagnosed with nutcracker syndrome. She suffered from syncope, sometimes multiple episodes in one day. Her other symptoms included unilateral hematuria, nausea, lower abdominal pain and weight loss. After she was treated with stenting of her left renal vein, her symptoms improved drastically and she had no episodes of syncope and her blood pressure normalized.[9]

Koshimichi et al. (2012) [4] reported that of 53 pediatric patients diagnosed with left renal vein entrapment syndrom (another term for nutcracker phenomenon), 22 patients (42%) suffered from orthostatic disturbance. Of these 22 patients:

- 68% had general malaise and fatigue

- 64% had palpitation or shortness of breath

- 45% had severe abdominal pain

- 9% had increased pulse (21 beats per minute or more) on standing

There was an absence of micro/macro-hematuria in half of the patients. Proteinuria was absent in 59% of the patients. 18% of the patients had neither micro/macro-hematuria or proteinuria. Treatment with midodrine significantly decreased orthostasis scores. The most severe patients (6 of 22) had either low urinary cortisol or plasma cortisol, persistent in some and intermittent in some. These patients improved after being given a low oral dose of fludrocortisone acetate to maintain sufficient blood cortisol.

Epidemiology

Nutcracker syndrome/phenomenon is often described as "rare" in the medical literature, even though there's research indicating that it's a severely under-diagnosed condition.[1][2][6][3]

Varicocele is a known complication of nutcracker phenomenon.[1] Between 9.5%[1] and 15%[14] of all men globally are affected by varicocele. According to two separate studies, 30%[15] to 100%[16] of varicocele patients have nutcracker phenomenon. If one extrapolates these numbers, between 2.9-15% of all men suffer from nutcracker phenomenon. A minuscule percentage of these patients are ever diagnosed with nutcracker phenomenon.

There might be several reasons behind this under-diagnosing, including:

- wide spectrum of symptoms,[1][2][4][10][11][7][13][8] many of which are not well known in the medical community to be linked to nutcracker phenomenon.

- not all patients experience classic nutcracker syndrome symptoms like hematuria, abdominal pain, proteinuria[4][7][11]

- diagnostic criteria are not well defined[1]

- nutcracker phenomenon is not easily detectable using conventional means.[17][1] Standard CT is for example insufficient to diagnose nutcracker phenomenon.[1]

Diagnosis

This quote is from Dysautonomia Information Network's website,[5] where Dr. Takahashi (the author of some of the studies linking nutcracker phenomenon to CFS & orthostatic intolerance) explains the methods used to diagnose nutcracker phenomenon:

"The methods used to diagnose nutcracker phenomenon include Doppler US, MRI and three-dimensional helical computed tomography. Dr. Takahashi (personal communication, September 8, 2002) explains the procedures for testing as follows: Conventional ultrasound requires patients to be examined for left renal vein obstruction in 4 positions: supine, semisitting, upright and prone. Nonvisualization of the left renal vein lumen or absence of the left renal vein wall between the aorta and superior mesenteric artery is regarded as signifying left renal vein obstruction. Doppler color flow imaging can be used to locate a blue-colored blood stream flowing to the dorsal direction. This is a collateral vein flowing from the left renal vein into the paravertebral vein. With MRI, oblique coronal images along the left renal vein, and also axial images, are recommended to visualize the collateral veins around the left renal vein."

Notable studies

- 2000, Does severe nutcracker phenomenon cause pediatric chronic fatigue?[11]

- 2000, An effective "transluminal balloon angioplasty" therapy for pediatric chronic fatigue syndrome with nutcracker phenomenon[7] - (Abstract)

- 2000, Clinical and radiological features in four adolescents with nutcracker syndrome[8] - (Abstract)

- 2005, An ultrasonographic classification for diverse clinical symptoms of pediatric nutcracker phenomenon[13]

- 2012, Nutcracker syndrome: symptoms of syncope and hypotension improved following endovascular stenting[9]

- 2012, Newly-identified symptoms of left renal vein entrapment syndrome mimicking orthostatic disturbance[4]

- 2017, A Tough Nut to Crack: Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Abdominal Pain Attributed to Nutcracker Syndrome[10] - (Full text)

See also

Learn more

- Renal nutcracker syndrome - Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center

- Nutcracker Syndrome - Wikipedia

- Renal Vein Entrapment And Orthostatic Intolerance - DINET

- Renal Nutcracker Syndrome Support Group - Facebook

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 Kurklinsky, Andrew K.; Rooke, Thom W. (June 2010). "Nutcracker Phenomenon and Nutcracker Syndrome". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 85 (6): 552–559. doi:10.4065/mcp.2009.0586. ISSN 0025-6196. PMC 2878259. PMID 20511485.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Scholbach, Thomas (2007). "From the nutcracker-phenomenon of the left renal vein to the midline congestion syndrome as a cause of migraine, headache, back and abdominal pain and functional disorders of pelvic organs". Medical Hypotheses. 68 (6): 1318–1327. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2006.10.040. ISSN 0306-9877. PMID 17161550.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Poyraz, Ahmet K; Firdolas, Fatih; Onur, Mehmet R; Kocakoc, Ercan (March 2013). "Evaluation of left renal vein entrapment using multidetector computed tomography". Acta Radiologica. 54 (2): 144–148. doi:10.1258/ar.2012.120355. ISSN 0284-1851.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Koshimichi, Machiko; Sugimoto, Keisuke; Yanagida, Hidehiko; Fujita, Shinsuke; Miyazawa, Tomoki; Sakata, Naoki; Okada, Mitsuru; Takemura, Tsukasa (April 2012). "Newly-identified symptoms of left renal vein entrapment syndrome mimicking orthostatic disturbance". World journal of pediatrics: WJP. 8 (2): 116–122. doi:10.1007/s12519-012-0349-1. ISSN 1867-0687. PMID 22573421.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 "What Causes POTS?". Dysautonomia Information Network (DINET). Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 "Renal nutcracker syndrome | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Takahashi, Y.; Sano, A.; Matsuo, M. (January 2000). "An effective "transluminal balloon angioplasty" therapy for pediatric chronic fatigue syndrome with nutcracker phenomenon". Clinical Nephrology. 53 (1): 77–78. ISSN 0301-0430. PMID 10661488.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Takemura, T.; Iwasa, H.; Yamamoto, S.; Hino, S.; Fukushima, K.; Isokawa, S.; Okada, M.; Yoshioka, K. (September 2000). "Clinical and radiological features in four adolescents with nutcracker syndrome". Pediatric Nephrology (Berlin, Germany). 14 (10–11): 1002–1005. doi:10.1007/s004670050062. ISSN 0931-041X. PMID 10975316.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Daily, Ryan; Matteo, Jerry; Loper, Todd; Northup, Martin (December 2012). "Nutcracker syndrome: symptoms of syncope and hypotension improved following endovascular stenting". Vascular. 20 (6): 337–341. doi:10.1258/vasc.2011.cr0320. ISSN 1708-5381. PMID 22734085.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Hammami M, Bader; W Meeks, Marshall; Omran M, Louay (2017). "A Tough Nut to Crack: Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Abdominal Pain Attributed to Nutcracker Syndrome". Internal Medicine and Care. 1 (1). doi:10.15761/imc.1000101. ISSN 2515-1061.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 Takahashi, Y.; Ohta, S.; Sano, A.; Kuroda, Y.; Kaji, Y.; Matsuki, M.; Matsuo, M. (March 2000). "Does severe nutcracker phenomenon cause pediatric chronic fatigue?". Clinical Nephrology. 53 (3): 174–181. ISSN 0301-0430. PMID 10749295.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Shin, Jae Il; Lee, Jae Seung (May 2006). "Comment on Gastrointestinal Symptoms Associated with Orthostatic Intolerance". Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 42 (5): 588. doi:10.1097/01.mpg.0000215310.71040.c0. ISSN 0277-2116.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Takahashi, Y.; Sano, A.; Matsuo, M. (July 2005). "An ultrasonographic classification for diverse clinical symptoms of pediatric nutcracker phenomenon". Clinical Nephrology. 64 (1): 47–54. doi:10.5414/cnp64047. ISSN 0301-0430. PMID 16047645.

- ↑ Kupis, Łukasz; Dobroński, Piotr Artur; Radziszewski, Piotr (2015). "Varicocele as a source of male infertility – current treatment techniques". Central European Journal of Urology. 68 (3): 365–370. doi:10.5173/ceju.2015.642. ISSN 2080-4806. PMC 4643713. PMID 26568883.

- ↑ Mohamadi, Afshin; Ghasemi-Rad, Mohammad; Mladkova, Nikol; Masudi, Sima (2010). "Varicocele and Nutcracker Syndrome". Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 29 (8): 1153–1160. doi:10.7863/jum.2010.29.8.1153. ISSN 1550-9613.

- ↑ Unlu, Murat; Orguc, Sebnem; Serter, Selim; Pekindil, Gokhan; Pabuscu, Yuksel (2007). "Anatomic and hemodynamic evaluation of renal venous flow in varicocele formation using color Doppler sonography with emphasis on renal vein entrapment syndrome". Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. 41 (1): 42–46. doi:10.1080/00365590600796659. ISSN 0036-5599. PMID 17366101.

- ↑ Matsukura, Hiro; Arai, Miwako; Miyawaki, Toshio (February 2005). "Nutcracker phenomenon in two siblings of a Japanese family". Pediatric Nephrology (Berlin, Germany). 20 (2): 237–238. doi:10.1007/s00467-004-1682-y. ISSN 0931-041X. PMID 15599773.