Herpesviruses

Herpesviruses are a family of DNA viruses, with the eight herpesviruses having very high prevalence rates in humans being known as human herpesviruses.[1] Once someone is infected with a herpesvirus, the infection is life-long; many herpesviruses have treatments that can suppress any symptoms but there is no cure.[2] While generally, immunocompetent hosts are able to keep the virus in a latent state and remain asymptomatic, human herpesviruses can cause symptoms if they reactivate. They can also increase the risk of autoimmune disease and cancer.[1][3]

Types[edit | edit source]

Viruses in the herpesvirus family that can infect humans include:

Alphaherpesviruses[edit | edit source]

- latent Herpes simplex virus#HSV-1 (HSV-1 or HHV1)

- Herpes simplex virus#HSV-2 (HSV-2 or HHV2)

- Varicella zoster virus (VZV or HHV3), which causes chickenpox and may reactivate to cause shingles

Betaherpesviruses[edit | edit source]

- Human herpesvirus 6 viruses including (HHV-6a and HHV-6b)

- Human herpesvirus 7 (HHV7)

- human cytomegalovirus (CMV, HCMB or HHV-5)

- Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV or HHV8)

Gammaherpesviruses[edit | edit source]

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV or HHV4), which causes mononucleosis.[4][5]

More than 90% of adults have been infected with at least one herpesvirus.

Latency[edit | edit source]

After the initial infection, herpesvirus usually remain latent for life (they are not curable), and may be reactivated later.[6]

Reactivation[edit | edit source]

Reactivation of herpesviruses do not usually cause disease,[7] although some may cause disease,[4] for example:

- reactivation of latent varicella-zoster virus may cause shingles (varicella zoster), typically in adults, with the virus typically being caught in childhood and resulting in chickenpox before becoming latent, and

- CMV pneumonia may be caused by CMV reactivation, which is most likely in immunosuppressed people, especially bone marrow transplant recipients and people with HIV.[4]

- HSV-1 has been implicated in Alzheimer's, although this does not mean it is the only cause.[8]

Several of the herpesviruses have transactivating potential, that is, they can cause the increased rate of gene expression of other viruses.[6]

Chronic fatigue syndrome[edit | edit source]

It is unclear whether herpesviruses associated with Chronic fatigue syndrome play an etiological role or are "bystanders" – opportunistic reactivations under a state of immune dysregulation. In the 1984 Incline Village chronic fatigue syndrome outbreak, Gary Holmes found that patients with what his team hypothesized was chronic Epstein-Barr had elevated antibody titers to Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex and measles viruses than age-matched controls.[9] However, the study cohort was defined as patients who had experienced excessive fatigue between January 1 and September 15.

A prospective study of 250 primary care patients revealed a higher prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome after infectious mononucleosis (glandular fever) when compared to an ordinary upper respiratory tract infection.[10] Anti-early antigen titers to Epstein-Barr virus were elevated in CFS patients and associated with worse symptoms.[11]

[edit | edit source]

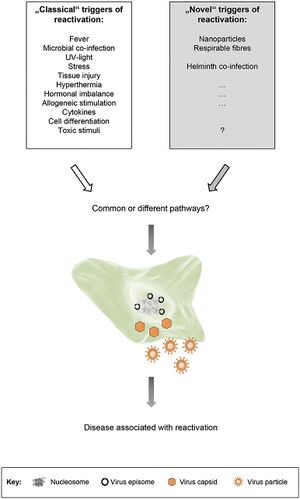

- 2019, "Novel" Triggers of Herpesvirus Reactivation and Their Potential Health Relevance[7] - (Full text)

- opinion article

"In this review, we provide evidence from animal and human studies of the Epstein-Barr virus as a prototype, supporting the notion that herpesviruses dUTPases are a family of proteins with unique immunoregulatory functions that can alter the inflammatory microenvironment and thus exacerbate the immune pathology of herpesvirus-related diseases including myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, autoimmune diseases, and cancer...[we] approached the possibility that two or more herpesviruses may act synergistically and that virus-encoded proteins, rather than the viruses themselves, may act as drivers of or contribute to the pathophysiological alterations observed in a subset of patients with ME/CFS."[12]

See also[edit | edit source]

- Human herpesvirus 6

- List of herpesvirus infection studies

- Valaciclovir

- Abortive infection theory of ME/CFS (Dr Lerner's theory that abortive herpesviruses cause ME/CFS)

Learn more[edit | edit source]

- 2018, A Common Virus May Play Role in Alzheimer’s Disease, Study Finds by Pam Belluck via NY Times

- 2018, Could Crippled Herpesviruses Be Contributing to Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) and Other Diseases? by Cort Johnson for Simmaron Research

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 White, Douglas W.; Beard, R. Suzanne; Barton, Erik S. (January 2012). "Immune Modulation During Latent Herpesvirus Infection". Immunological reviews. 245 (1): 189–208. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01074.x. ISSN 0105-2896. PMC 3243940. PMID 22168421.

- ↑ Dong, Haisi; Wang, Zeyu; Zhao, Daqing; Leng, Xiangyang; Zhao, Yicheng (September 1, 2021). "Antiviral strategies targeting herpesviruses". Journal of Virus Eradication. 7 (3): 100047. doi:10.1016/j.jve.2021.100047. ISSN 2055-6640. PMC 8187247. PMID 34141443.

- ↑ "Viruses that can lead to cancer". cancer.org. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Template:Cite boom

- ↑ Davison, Andrew J. (2007). "1 Overview of classification". In Arvin, Ann; Campadelli-Fiume, Gabriella; Mocarski, Edward; Moore, Patrick S.; Roizman, Bernard; Whitley, Richard; Yamanishi, Koichi (eds.). Overview of classification. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82714-0. PMID 21348096.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 De Bolle, Leen; Naesens, Lieve (January 2005), "Update on Human Herpesvirus 6 Biology, Clinical Features, and Therapy", Clin Microbiol Rev, 8 (1): 217–245, doi:10.1128/CMR.18.1.217-245.200

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Stoeger, Tobias; Adler, Heiko (2019). ""Novel" Triggers of Herpesvirus Reactivation and Their Potential Health Relevance". Frontiers in Microbiology. 9. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.03207. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 6330347. PMID 30666238.

- ↑ Experts Say There’s a Herpes-Alzheimer’s Link, Time, March 10, 2016

- ↑ Homes, Gary P (May 1, 1987). "A Cluster of Patients With a Chronic Mononucleosis-like Syndrome Is Epstein-Barr Virus the Cause?". Journal of the American Medical Association. 257: 2297–2302.

- ↑ White, P.D.; Thomas, J.M.; Amess, J.; Crawford, D.H.; Grover, S.A.; Kangro, H.O.; Clare, A.W. (December 1998). "Incidence, risk and prognosis of acute and chronic fatigue syndromes and psychiatric disorders after glandular fever". The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science. 173: 475–481. ISSN 0007-1250. PMID 9926075.

- ↑ Schmaling, K.B.; Jones, J.F. (January 1996). "MMPI profiles of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome". Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 40 (1): 67–74. ISSN 0022-3999. PMID 8730646.

- ↑ Williams, Marshall V.; Cox, Brandon; Ariza, Maria Eugenia (2017), "Herpesviruses dUTPases: A New Family of Pathogen-Associated Molecular Pattern (PAMP) Proteins with Implications for Human Disease", Pathogens, 6 (1): 2, doi:10.3390/pathogens6010002