PACE trial: Difference between revisions

(→List of Media & Blog Coverage: Added Guardian article) |

|||

| Line 212: | Line 212: | ||

===[[Angela Kennedy]], a sociologist of science, health, disability and medicine=== | ===[[Angela Kennedy]], a sociologist of science, health, disability and medicine=== | ||

Kennedy has made specific critiques of PACE regarding the following areas: <ref>[http://pacedocuments.blogspot.co.uk/2016/02/summary-of-my-specific-concerns-about.html Summary of my specific concerns about PACE with annotated bibliography]</ref> | |||

1. Serious risks to clinical patient safety caused by unsound claims made about the efficacy of CBT and GET following the PACE trial; | 1. Serious risks to clinical patient safety caused by unsound claims made about the efficacy of CBT and GET following the PACE trial; | ||

Revision as of 11:01, February 15, 2016

The PACE Trial (formally called "Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome (PACE): a randomised trial") was a large-scale trial to test and compare the effectiveness of four treatments for people suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), also known as myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME).

The four treatments tested were adaptive pacing therapy (APT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), Graded Exercise Therapy (GET), and standardised Specialist Medical Care (SMC).[1] The trial found that CFS/ME patients in the CBT and GET groups had greater improvement in self-reported scores when compared to adaptive pacing or specialist care. Both the trial design and the conclusions drawn from it have been heavily criticized by patients and scientists.[2][3]

The PACE trial dominates clinical policy in the United Kingdom and other countries, both government funded health care[4] and private medical insurance.[5]

Background[edit | edit source]

The protocol paper was published in BMC Neurology in 2007.[6] The main study was published in The Lancet in 2011.[7].

The principal investigators include Peter White, Trudie Chalder, and Michael Sharpe. Although not an author, Professor Simon Wessely advised the authors and provided feedback.[8]

Professor Simon Wessely stated in November 2015 that "there are also more trials in the pipeline".[9]

Findings[edit | edit source]

The PACE trial found that CFS/ME patients in the CBT and GET groups had greater improvement in self-reported scores when compared to adaptive pacing or specialist care.

Impact[edit | edit source]

The PACE trial and other Oxford studies have had major international impact on popular perceptions of ME/CFS and also on public policies toward treating and researching the disease.

Media[edit | edit source]

On February 27, 2011, upon the initial publication of the PACE trial, researchers Michael Sharpe and Trudie Chalder held a press conference[10] to discuss their findings. Chalder stated, “twice as many people on graded exercise therapy and cognitive behaviour therapy got back to normal.” That assertion has been criticized for grossly overstating the study's actual findings.[11]

The study led to press coverage around the world including The Daily Mail which stated, "Fatigued patients who go out and exercise have best hope of recovery." The New York Times declared "Psychotherapy Eases Chronic Fatigue Syndrome." According to the British Medical Journal's report on the trial, some participants were "cured."[12]

A long-term follow-up paper was then published in The Lancet Psychiatry in October 2015.[13] The Daily Telegraph, in a piece that was altered many days after publication under public pressure and without a formal retraction, ran a front page story with the headline, "Exercise and positivity ‘can overcome ME." The piece further reported that "Chronic Fatigue Syndrome is not actually a chronic illness and sufferers can overcome symptoms by increasing exercise and thinking positively, Oxford University has found" and quoted Sharpe describing ME as a “self-fulfilling prophesy” that happens when patients live within their limits.[14]

Research and treatment[edit | edit source]

The PACE trial dominates clinical policy in the United Kingdom and other countries, both government funded health care[15] and private medical insurance.[16]

In research, PACE and other Oxford studies confound the research evidence base with studies that included patients with other conditions. It is for this reason that a 2015 report by the U.S. National Institute of Health called for the Oxford definition to be retired.

PACE and other Oxford studies also have an impact on how ME/CFS patients are treated clinically through their impact on "evidence-based" clinical guidelines. For instance, in the U.K., the primary treatment recommendations are for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and graded exercise therapy (GET) based largely on the results of Oxford studies. In the U.S., a number of medical education providers, including the CDC, recommend CBT and GET and/or link poor prognosis to a belief that the disease is organic. These recommendations and findings are based on PACE or other Oxford studies.

This impact of PACE and other Oxford studies on clinical guidelines is still seen even after the 2015 Institute of Medicine report on ME/CFS, which stated that the disease was not psychological and was characterized by a systemic intolerance to even trivial activity. One example is UpToDate, whose clinical guidelines recommend the IOM criteria for diagnosis and PACE style CBT and GET for treatment, even though such treatment would be inappropriate for patients diagnosed by the IOM criteria.[17]

Criticisms of the study[edit | edit source]

Patient selection[edit | edit source]

Changing recovery criteria[edit | edit source]

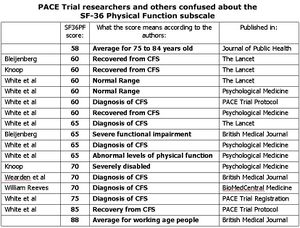

Many critics have noted that the criteria for "recovery" on the SF-36 physical function scale, by PACE's standards, were broader than the criteria for entry, meaning that one could be simultaneously sick with "chronic fatigue syndrome" and recovered as per their recovery threshold.

In the Lancet paper, the outcome thresholds for being in the "normal range" for physical function was 60 or above, lower than the threshold for disability required to be enrolled in the trial in the first place.[18] In a paper published in Psychological Medicine, the original recovery threshold was 85 but was later changed to 60 and above.[19]

Outcome measures[edit | edit source]

Two critiques of outcome measures have been made. First, that the outcome measures were changed in the middle trial. Second, that only subjective measures were reported, even though the original study protocol included a six minute walking test. Critics argue that this is particularly concerning given that the trial investigators were not blind to participants' treatment assignments.[20][21]

Conflicts of interest[edit | edit source]

Newsletter to participants[edit | edit source]

The investigators published a newsletter for participants[22] while the trial was still underway, which critics say could have influenced the self-reported outcomes. While the newsletter does not refer to the different treatment conditions by name, it includes positive testimonials by patients that suggest behavioral interventions:

- “(The therapist) is very helpful and gives me very useful advice and also motivates me.”

- “I really enjoyed being a part of the PACE Trial. It helped me to learn more about myself, especially (treatment), and control factors in my life that were damaging.

It also contained less positive assessment of research on the possibility of an infectious component, including research by Jose Montoya on herpesviruses and by John Chia on enteroviruses:

- The laboratory work looked convincing, but many patients had significant gastro-intestinal symptoms and even signs, casting some doubt on the diagnoses of CFS being the correct or sole diagnosis in these patients.

And positive assessment of CBT:

- "cognitive behaviour therapy was associated with an increase in grey matter of the brain and this increase was associated with improved cognitive function

Risks and side effects[edit | edit source]

An informal survey conducted by the ME Association in 2012 showed that 80% of patients had their symptoms worsen after a course of GET. [23]

Controversy[edit | edit source]

The PACE Trial has been heavily criticised by patient groups and some researchers and science journalists for a number of methodological problems since its publication.[24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40]

Renewed interest in the trial came in October 2015 with investigative journalist David Tuller's publication of Trial by Error, a four-part series analyzing its PACE's possible methodological weaknesses.[41]

On October 30, 2015, the PACE trial investigators' response to these criticisms was published on the Virology Blog.[42].

Open letter to the Lancet[edit | edit source]

As of November 13, 2015, a total of 41 researchers have signed an open letter to the Lancet citing major flaws in the original trial publication and asking for an independent re-analysis of the individual-level PACE trial data.[43]

The initial letter was submitted in December 2015 and included Ronald Davis, David Tuller, Vincent Racianiello, Jonathan Edwards, Leonard Jason, Bruce Levin and Arthur Reingold. The journal failed to respond.[44]

In February 2016 the open letter was re-published with 36 additional doctors and researchers including: Dharam Ablashi, Lisa Barcellos, James Baraniuk, Lucinda Bateman, David Bell, Alison Bested, Gordon Broderick, John Chia, Lily Chu, Derek Enlander, Mary Ann Fletcher, Kenneth Friedman, David Kaufman, Nancy Klimas, Charles Lapp, Susan Levine, Alan Light, Sonya Marshall-Gradisnik, Peter Medveczky, Zaher Nahle, James Oleske, Richard Podell, Charles Shepherd, Christopher Snell, Nigel Speight, Donald Staines, Philip Stark, John Swartzberg, Ronald Tompkins, Rosemary Underhill, Rosamund Vallings, Michael VanElzakker, William Weir, Marcie Zinn and Mark Zinn.[45]

Petitions[edit | edit source]

On November 24, 2015, MEAction launched a petition to the Lancet and Psychological Medicine calling for an independent analysis and the retraction of some of the PACE trial's conclusions. The petition was closed in February 2016, having gathered 11,897 signatures from sixty-four countries.[46]

A US petition to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Centers for Disease Control was also launched, asking government agencies to remove guidelines and recommendations based on PACE and other studies using the Oxford definition.[47]

Calls to release data[edit | edit source]

Freedom of Information requests[edit | edit source]

There have been a number of Freedom of Information requests in relation to the PACE trial made under British freedom of information laws asking that anonymized PACE trial data be released.[48] The PACE trial investigators dismissed at least three of these claims as "vexatious" [49][50]

A ruling by the UK government body the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) on 27 October 2015 compelled Queen Mary University of London (home of the PACE trial's lead investigator Peter White to release the trial data, subject to appeal within 28 days.[51] Three freedom of information requests from 2012 and 2013 were included in the ICO decision.[52][53][54]

The patient consent form was also released through a Freedom of Information request.[55]

The investigators have claimed they have received 150 freedom of information requests in relation to the PACE trial, but they are counting each piece of data requested as a request. The total number of FOI requests is 34.[56]

Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet, stated on 18 April 2011 in an Australian radio interview "The freedom of information requests and the legal fees that have been wracked up over the years because of these vexatious claims has added another £750,000 of taxpayers’ money to the conduct of this study".[57]

Requests from scientists[edit | edit source]

Professor Coyne has publicly called for the trial data to be released and made a request to the PACE authors in late 2015 to release the data related to the cost-effectiveness follow-up paper published in PLOS One in 2012, as required by the terms of journal. Professor Coyne has repeatedly criticized the PACE investigators and supporters for failing to abide by modern expectations of open-data.[58][59][60][61]

Professor Coyne's request for the data was refused. The investigators deemed his request "vexatious" and accused him of "improper motive".[62]

Ronald Davis, David Tuller, Bruce Levin, and Vincent Racaniello requested the PACE trial data in December 2015.[63] Their request was rejected by the trial investigators.[64]

Other calls for data release[edit | edit source]

- 2016, the British charity Action for ME has called for the trial to be released.[65]

- 2016, the British charity Invest in ME has called for the trial data to be released.[66]

- 2016, The British ME Association has called for the trial data to be released.[67]

- 2015, Professor Andrew Gelman, a statistician at Columbia University, says "when researchers refuse to share data, and how they came up with it, they lose the right to call what they do science".[68]

- 2015, Richard Smith, former editor of The BMJ, called for the PACE trial data to be released.[69]

Allegations of harassment[edit | edit source]

Criticism by patients of the trial has been rebuffed by the investigators, who have accused patents of harassment. Investigators and Professor Simon Wessely have publicly claimed they have been harassed and subjected to death threats.[70][71][72][73][74][75]

Some accuse the investigators of a campaign against patients, labelling them as harassers to deflect attention, including Angela Kennedy[76] and journalist David Tuller[77]

Patient Data Breaches[edit | edit source]

In 2006 confidential PACE trial patient data was stolen from an unlocked drawer at Kings College London.[78]

Malcolm Hooper documents in Magical Medicine how in 2005 confidential patient data was erroneously released by PACE author Professor Michael Sharpe[79] in relation to another study.

Quotes by PACE trial critics[edit | edit source]

Professor Ronald Davis, Stanford University[edit | edit source]

“I’m shocked that the Lancet published it…The PACE study has so many flaws and there are so many questions you’d want to ask about it that I don’t understand how it got through any kind of peer review.”

Dr. Bruce Levin, Columbia University[edit | edit source]

“To let participants know that interventions have been selected by a government committee ‘based on the best available evidence’ strikes me as the height of clinical trial amateurism.”

Dr. Arthur Reingold, University of California, Berkeley[edit | edit source]

- “Under the circumstances, an independent review of the trial conducted by experts not involved in the design or conduct of the study would seem to be very much in order.”[80]

Dr. Jonathan Edwards, University College London[edit | edit source]

“It’s a mass of un-interpretability to me…All the issues with the trial are extremely worrying, making interpretation of the clinical significance of the findings more or less impossible.”

Dr. Leonard Jason, DePaul University[edit | edit source]

“The PACE authors should have reduced the kind of blatant methodological lapses that can impugn the credibility of the research, such as having overlapping recovery and entry/disability criteria.”

Professor James Coyne, University Medical Center, Groningen[edit | edit source]

- "The data presented are uninterpretable. We can temporarily suspend critical thinking and some basic rules for conducting randomized trials (RCTs), follow-up studies, and analyzing the subsequent data. Even if we do, we should reject some of the interpretations offered by the PACE investigators as unfairly spun to fit what has already a distorted positive interpretation of the results."

- "The self-report measures do not necessarily capture subjective experience, only forced choice responses to a limited set of statements."

- "One of the two outcome measures, the physical health scale of the SF-36 requires forced choice responses to a limited set of statements selected for general utility across all mental and physical conditions."

- "Despite its wide use, the SF-36 suffers from problems in internal consistency and confounding with mental health variables. Anyone inclined to get excited about it should examine its items and response options closely. Ask yourself, do differences in scores reliably capture clinically and personally significant changes in the experience and functioning associated with the full range of symptoms of CHF?"

- "The validity other primary outcome measure, the Chalder Fatigue Scale depends heavily on research conducted by this investigator group and has inadequate validation of its sensitivity to change in objective measures of functioning."

- "Such self-report measures are inexorably confounded with morale and nonspecific mental health symptoms with large, unwanted correlation tendency to endorse negative self-statements that is not necessarily correlated with objective measures."

Professor Coyne spoke critically about the PACE trial at Edinburgh University in November 2015.[81][82][83][84][85][86]

He spoke again about the PACE study in Belfast in February 2016 where he described it as "A wasteful trainwreck of a study".</ref>The scandal of the £5m PACE chronic fatigue trial</ref>

Professor Coyne has questioned whether the PACE trial paper could ever have been properly peer-reviewed.[87]

James Coyne & Keith Laws[edit | edit source]

Coyne and Laws have criticised the 2015 long-term follow-up PACE trial.[88]

- " the overall mean short-form 36 (SF-63) physical functioning score is less than 60. It is useful to put this number in context. 77% of the PACE trial participants were women, and the mean age of the trial population was 38 years, with no other disabling medical conditions. Patients with lupus have a mean physical functioning score of 63,2 patients with class II congestive heart failure have a mean score lower than 60,3 and normal controls with no long-term health problems have a mean score of 93."

Charles Shepherd[edit | edit source]

Dr Shepherd, medical advisor to the ME Association has criticised the trial long-term follow-up.[89]

- "Without robust objective evidence relating to improvement and recovery, the ME patient community will continue to regard the PACE trial as a tremendous waste of research funding money"

David Tuller, Public health journalist, University of California, Berkeley[edit | edit source]

- "The study included a bizarre paradox: participants’ baseline scores for the two primary outcomes of physical function and fatigue could qualify them simultaneously as disabled enough to get into the trial but already “recovered” on those indicators–even before any treatment. In fact, 13 percent of the study sample was already “recovered” on one of these two measures at the start of the study."

- "In the middle of the study, the PACE team published a newsletter for participants that included glowing testimonials from earlier trial subjects about how much the “therapy” and “treatment” helped them. The newsletter also included an article informing participants that the two interventions pioneered by the investigators and being tested for efficacy in the trial, graded exercise therapy and cognitive behavior therapy, had been recommended as treatments by a U.K. government committee “based on the best available evidence.” The newsletter article did not mention that a key PACE investigator was also serving on the U.K. government committee that endorsed the PACE therapies."

- "The PACE team changed all the methods outlined in its protocol for assessing the primary outcomes of physical function and fatigue, but did not take necessary steps to demonstrate that the revised methods and findings were robust, such as including sensitivity analyses. The researchers also relaxed all four of the criteria outlined in the protocol for defining “recovery.” They have rejected requests from patients for the findings as originally promised in the protocol as “vexatious.” "

- "The PACE claims of successful treatment and “recovery” were based solely on subjective outcomes. All the objective measures from the trial—a walking test, a step test, and data on employment and the receipt of financial information—failed to provide any evidence to support such claims. Afterwards, the PACE authors dismissed their own main objective measures as non-objective, irrelevant, or unreliable."

- "In seeking informed consent, the PACE authors violated their own protocol, which included an explicit commitment to tell prospective participants about any possible conflicts of interest. The main investigators have had longstanding financial and consulting ties with disability insurance companies, having advised them for years that cognitive behavior therapy and graded exercise therapy could get claimants off benefits and back to work. Yet prospective participants were not told about any insurance industry links and the information was not included on consent forms. The authors did include the information in the “conflicts of interest” sections of the published papers."

- "The Lancet Psychiatry follow-up had null findings: Two years or more after randomization, there were no differences in reported levels of fatigue and physical function between those assigned to any of the groups.... Yet the authors, once again, attempted to spin this mess as a success."[90]

David Tuller & Julie Rehmeyer[edit | edit source]

Tuller & Rehmeyer have written critically about PACE claims regarding the safety of Graded exercise therapy.[91]

- "The study’s primary case definition for identifying participants, called the Oxford criteria, was extremely broad; it required only six months of medically unexplained fatigue, with no other symptoms necessary. Indeed, 16% of the participants didn’t even have exercise intolerance—now recognized as the primary symptom of ME/CFS"

- "After the trial began, the researchers tightened their definition of harms, just as they had relaxed their methods of assessing improvement."

- "the study was unblinded, so both participants and therapists knew the treatment being administered. Many participants were probably aware that the researchers themselves favored graded exercise therapy and another treatment, cognitive behavior therapy, which also involved increasing activity levels. Such information has been shown in other studies to lead to efforts to cooperate, which in this case could lead to lowered reporting of harms."

Tom Kindlon[edit | edit source]

Mr Kindlon is a patient who has published extensive criticism of the PACE trial. In 2011 he published a paper on harms associated with Graded exercise therapy.[92]

Dr Ellen Goudsmit[edit | edit source]

"The PACE trial was scientifically extremely poor"[93]

Frank Twisk[edit | edit source]

Twisk has criticised the PACE trial.[94]

- "The PACE trial investigated the effects of CBT and GET in chronic fatigue, as defined by the Oxford criteria, not in chronic fatigue syndrome, let alone myalgic encephalomyelitis"

- "the positive effect of CBT and GET in subjective measures, fatigue and physical functioning, cannot be qualified as sufficient. Mean short form-36 physical functioning scores in the CBT group (62·2) and the GET group (59·8) at follow-up were below the inclusion cutoff score for the PACE trial (≤65)3 and far below the objective for recovery as defined in the PACE protocol (≥85)"

- "The vast majority of patients improved subjectively by specialist medical care and APT to the same level as by CBT and GET, without any additional therapies, including CBT and GET, or by other therapies"

- "looking at subjective outcomes at follow-up1 and objective outcomes in earlier studies, such as physical fitness,2 return to employment,3 social welfare benefits,3 and health-care usage,3 CBT and GET, like specialist medical care and APT, cannot be qualified as effective"

Robert Courtney[edit | edit source]

- "Chalder and colleagues acknowledge that the trial outcomes do not support the hypothetical deconditioning model of GET for chronic fatigue syndrome"[95]

Angela Kennedy, a sociologist of science, health, disability and medicine[edit | edit source]

Kennedy has made specific critiques of PACE regarding the following areas: [96]

1. Serious risks to clinical patient safety caused by unsound claims made about the efficacy of CBT and GET following the PACE trial;

2. Gross discrepancies between research and clinical cohorts, and how clinical patients (and the physiological dysfunction associated with them) appear to have been actively excluded from PACE and other research by the research group involved in PACE, which has, ironically, caused serious resulting risks to clinical patient safety in the UK in particular;

3. Related to the above, gross discrepancies in how various sets of patient criteria were used (and/or rejected), including but not limited to a changing of the London criteria by PACE authors from its original state, a set of criteria which was already controversial and problematic to start with for a number of reasons;

4. Failure of the PACE trial authors to acknowledge the range and depth of scientific literature documenting serious physiological dysfunction in patients given diagnoses of ME or CFS, and how CBT and GET approaches may endanger patients in this context;

5. The inclusion of major mental illnesses in the research cohort;

6. The distortion by PACE trial researchers of 'pacing' from an autonomous flexible management strategy for patients into a therapist led Graded Activity approach;

7. The post hoc dismissal of adverse outcomes as irrelevant to the trial, in direct contradiction to what is scientifically known about the physiological dysfunctions of people given diagnoses of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome ;

8. The instability of 'specialist medical care' as a treatment category, and the lack of any sound category of 'control' group.

Analysis by Patient "Citizen-Scientists"[edit | edit source]

Graham McPhee, Tom Kindlon and others collaborated to take the results of their analyses of the PACE trial and create a set of explanatory videos to communicate the flaws that they had found.

Graham McPhee and Janelle Wiley also collaborated with others to create a web site summarising their critical findings.

Tom Kindlon has also has also written a larger number of e-letters and comments in response to the published papers.

MEAction has published an overview of PACE and its flaws.[97]

A patient pointed out the significant inconsistency between SF-36 function scores for entry and recovery across various studies.[98]

Investigators[edit | edit source]

- Peter White

- KA Goldsmith

- AL Johnson

- L Potts

- R Walwyn

- JC DeCesare

- HL Baber

- M Burgess

- LV Clark

- DL Cox

- Jessica Bavinton

- BJ Angus

- Gabrielle Murphy

- M Murphy

- H O'Dowd

- D Wilks

- P McCrone

- Trudie Chalder

- Michael Sharpe

List of PACE trial publications[edit | edit source]

2012 Cost-effectiveness Paper[edit | edit source]

A 2012 PACE paper was published in PLOS One on cost-effectiveness.[99]

2013 "Recovery" Paper[edit | edit source]

A PACE Trial "recovery" paper was published in Psychological Medicine in 2013.[100] The Science Media Centre issued an "expert opinion" about the study.[101]

Patient Graham McPhee and others created a video animation examining the results of the paper: How's that recovery?.

2013 Statistical Analysis Paper[edit | edit source]

This 2013 paper published in Trials Journal further examined the PACE data.[102]

2014 Adverse Effects Paper[edit | edit source]

This 2014 paper published in the Journal of Psychosomatic Research examined adverse effects and deterioration.[103]

2015 Secondary Mediation Analysis[edit | edit source]

This 2015 paper was published in The Lancet Psychiatry. Rehabilitative therapies for chronic fatigue syndrome: a secondary mediation analysis of the PACE trial (Trudie Chalder, Goldsmith KA, Peter White, Michael Sharpe, Pickles AR)

The paper has been criticised by Byron Hyde.[104]

2015 Long-term Follow-up Paper[edit | edit source]

A long-term follow-up paper was then published in The Lancet Psychiatry in October 2015.[105] The Science Media Centre published expert opinion on the paper.[106]

2015 Longitudinal Mediation Paper[edit | edit source]

This short paper published in Trials Journal on 16 November 2015 concludes "Approximately half of the effect of each of CBT and GET were on physical function was mediated through reducing avoidance of fearful situations".[107]

Other Publications[edit | edit source]

- 2014, Pain in chronic fatigue syndrome: response to rehabilitative treatments in the PACE trial

- 2013, The planning, implementation and publication of a complex intervention trial for chronic fatigue syndrome: the PACE trial

- 2013, Cognitions, behaviours and co-morbid psychiatric diagnoses in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome

- 2013, Training, Supervision & Therapists' Adherence to Manual Based Therapies

- 2011, Measuring disability in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: reliability and validity of the Work and Social Adjustment Scale

- 2010, Psychiatric misdiagnoses in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome

List of Media & Blog Coverage[edit | edit source]

- 2016, ‘It was like being buried alive’: battle to recover from chronic fatigue syndrome

- 2016, PACE trial and other clinical data sharing: patient privacy concerns and parasite paranoia

- 2016, TULLER: PACE AUTHORS “WRAPPING THEMSELVES IN VICTIMHOOD”

- 2016, PACE trial's forbidden fruit - is the data really poisonous?

- 2011, Radio National Australia (April 18)

- 2011, Expert Opinion (Science Media Centre, February 17)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ PACE Manual for doctors standardised specialist medical care (SSMC)

- ↑ An open letter to Dr. Richard Horton and The Lancet

- ↑ Petition: Misleading Claims Should Be Retracted

- ↑ NICE guidelines - Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy): diagnosis and management

- ↑ Managing claims for chronic fatigue the active way

- ↑ "Protocol for the PACE trial: A randomised controlled trial of adaptive pacing, cognitive behaviour therapy, and graded exercise as supplements to standardised specialist medical care versus standardised specialist medical care alone for patients with the chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis or encephalopathy"

- ↑ "Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome (PACE): a randomised trial"

- ↑ PubMed - Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome (PACE): a randomised trial

- ↑ "The PACE Trial for chronic fatigue syndrome: choppy seas but a prosperous voyage"

- ↑ Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, The Lancet TV

- ↑ http://www.virology.ws/2015/10/21/trial-by-error-i/, Virology Blog, October 21, 2015

- ↑ http://www.virology.ws/2015/10/21/trial-by-error-i/, Virology Blog, October 21, 2015

- ↑ "Rehabilitative treatments for chronic fatigue syndrome: long-term follow-up from the PACE trial"

- ↑ PACE trial controversy grows, #MEAction, October 28, 2015

- ↑ NICE guidelines - Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy): diagnosis and management

- ↑ Managing claims for chronic fatigue the active way

- ↑ UpToDate: Treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome (systemic exertion intolerance disease)

- ↑ What's Wrong in the Lancet, #MEAction

- ↑ What's Wrong in Psychological Medicine, #MEAction

- ↑ An open letter to Dr. Richard Horton and The Lancet, Virology Blog

- ↑ Prof. Jonathan Edwards: PACE trial is "valueless", #MEAction

- ↑ PACE trial participants' newsletter

- ↑ http://www.meassociation.org.uk/2015/05/23959/

- ↑ "Uninterpretable: Fatal flaws in PACE Chronic Fatigue Syndrome follow-up study"

- ↑ "James Coyne: A skeptical look at the PACE chronic fatigue trial (video talk at Edinburgh University 16 Nov 2015"

- ↑ "TRIAL BY ERROR: The Troubling Case of the PACE Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study"

- ↑ "TRIAL BY ERROR: The Troubling Case of the PACE Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study (second instalment)"

- ↑ "TRIAL BY ERROR: The Troubling Case of the PACE Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study (final instalment)"

- ↑ "David Tuller responds to the PACE Investigators"

- ↑ "Trial By Error, Continued: Did the PACE Study Really Adopt a ‘Strict Criterion’ for Recovery?"

- ↑ "Trial By Error, Continued: Why has the PACE Study’s Sister Trial been Disappeared and Forgotten?"

- ↑ "Trial by error, Continued: PACE Team’s Work for Insurance Companies Is “Not Related” to PACE. Really?"

- ↑ "PACE - Thoughts about Holes"

- ↑ "Song for Siren"

- ↑ "Hope for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome"

- ↑ "Edinburgh Skeptics in the Pub talk on PACE chronic fatigue trial"

- ↑ "Prof. Jonathan Edwards: PACE Trial is valueless"

- ↑ Invest in ME - To The Editor of the Lancet – The PACE Trial

- ↑ My thoughts about the PACE trial

- ↑ ME – the truth about exercise and therapy

- ↑ TRIAL BY ERROR: The Troubling Case of the PACE Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study, Virology Blog

- ↑ PACE trial investigators respond to David Tuller

- ↑ An open letter to Dr. Richard Horton and The Lancet

- ↑ "An open letter to Dr. Richard Horton and The Lancet"

- ↑ An open letter to the Lancet - again

- ↑ Petition: Misleading Claims Should Be Retracted

- ↑ Call for HHS to Investigate Pace

- ↑ "Search results 'pace trial'"

- ↑ PACE trial investigators respond to David Tuller

- ↑ James Coyne response

- ↑ "Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA) Decision notice"

- ↑ https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/pace_trial_recovery_rates_and_po_2

- ↑ https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/6min_walking_test_data_recovered

- ↑ https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/pace_trial_recovery_rates_and_po

- ↑ PACE trial protocol: Full Trial Consent Form with Missing Therapist and No Cover

- ↑ FOIA briefing note on how many PACE requests

- ↑ Professor Malcolm Hooper’s Detailed Response to Professor Peter White’s letter to Dr Richard Horton about his complaint re: the PACE Trial articles published in The Lancet

- ↑ "Why the scientific community needs the PACE trial data to be released"

- ↑ What it takes for Queen Mary to declare a request for scientific data “vexatious”

- ↑ Update on my formal request for release of the PACE trial data

- ↑ Further insights into war against data sharing: Science Media Centre’s letter writing campaign to UK Parliament

- ↑ James Coyne response

- ↑ A request for data from the PACE trial

- ↑ At least we're not vexatious

- ↑ Sharing research data: Board of Trustees states our position

- ↑ Invest in ME Letters to the Medical Research Council and Lancet

- ↑ ME Association writes in support of FoI request relating to release of PACE Trial data

- ↑ To keep science honest, study data must be shared

- ↑ Richard Smith: QMUL and King’s college should release data from the PACE trial

- ↑ Chronic fatigue syndrome researchers face death threats from militants

- ↑ Mind the gap - It’s time to stop separating psychiatry and neurology

- ↑ 'Malicious' harassment of ME researchers

- ↑ Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Death threats for scientists?

- ↑ Chronic Fatigue: Enough Energy Left for Death Threats, Anyway

- ↑ Interview with Professor Simon Wessely, The Times, 6 August 2011

- ↑ Statement re Simon Wessely and claims of harassment

- ↑ Trial By Error, Continued: A Few Words About “Harassment”

- ↑ Letter from Professor Peter White

- ↑ Twitter screenshot

- ↑ Trial By Error, Continued: More Nonsense from The Lancet Psychiatry

- ↑ "James Coyne: A skeptical look at the PACE chronic fatigue trial - Part 1"

- ↑ "James Coyne: A skeptical look at the PACE chronic fatigue trial - Part 2"

- ↑ "James Coyne: A skeptical look at the PACE chronic fatigue trial - Part 3"

- ↑ Complete talk transcript

- ↑ Summarised talk transcript

- ↑ Edited talk audio recording

- ↑ Was independent peer review of the PACE trial articles possible?

- ↑ Results of the PACE follow-up study are uninterpretable

- ↑ Patient reaction to the PACE trial

- ↑ Trial By Error, Continued: More Nonsense from The Lancet Psychiatry

- ↑ Trial By Error, Continued: Did the PACE Trial Really Prove that Graded Exercise Is Safe?

- ↑ Reporting of Harms Associated with Graded Exercise Therapy and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

- ↑ Response to article in the magazine published by the UK charity MCS-Aware

- ↑ PACE: CBT and GET are not rehabilitative therapies

- ↑ Doubts over the validity of the PACE hypothesis

- ↑ Summary of my specific concerns about PACE with annotated bibliography

- ↑ PACE Trial Overview

- ↑ PACE Trial researchers and others confused about the SF-36 Physical Function subscale

- ↑ "Adaptive Pacing, Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, Graded Exercise, and Specialist Medical Care for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis"

- ↑ "Recovery from chronic fatigue syndrome after treatments given in the PACE trial"

- ↑ expert reaction to new research into therapies for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/ME

- ↑ "A randomised trial of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome (PACE): statistical analysis plan"

- ↑ "http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022399914001883"

- ↑ Follow the money

- ↑ "Rehabilitative treatments for chronic fatigue syndrome: long-term follow-up from the PACE trial"

- ↑ expert reaction to long-term follow-up study from the PACE trial on rehabilitative treatments for CFS/ME, and accompanying comment piece

- ↑ "Longitudinal mediation in the PACE randomised clinical trial of rehabilitative treatments for chronic fatigue syndrome: modelling and design considerations"