Epidemiology of myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome

Incidence[edit | edit source]

Estimates of the prevalence vary widely, owing in part to the variety of definitions used. Estimates range from 0.025%[1] to 0.3% of the population.

In the US, it affects 836,000 to 2.5 million people.[2]

In Australia, up to 242,000 people have CFS (including 94,000 with ME which is a narrower definition).[3]

Severity[edit | edit source]

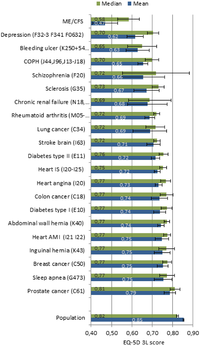

People with ME/CFS are more disabled and socially marginalized than for most other chronic illnesses.[4]

Around 25 per cent of people with ME/CFS will have a mild form and be able to get to school or work either part-time or full-time, while reducing other activities. About 50 per cent will have a moderate to severe form of ME/CFS and not be able to get to school or work. Another 25 per cent will experience severe ME/CFS and have to stay at home or in bed.[5]

In the US, 50-75% of patients with ME/CFS cannot work.[6]

Demographic factors[edit | edit source]

Gender[edit | edit source]

Various studies have estimated that 70-80% are women.[7]

Naviaux found women with ME/CFS, but not men, generally had disturbed fatty acid and endocannabinoid metabolism. Men, but not women, generally showed increased serine and threonine concentrations. [8]

Age[edit | edit source]

A study in Norway found two age peaks, one between 10 and 19 years and a second peak between 30 and 39 years.[9]

Race[edit | edit source]

Risk factors[edit | edit source]

Genetics[edit | edit source]

See also: genetics

5% of children of mothers with ME/CFS later developed the illness.[10]

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

On average, many people with ME/CFS will improve in the first five years, but others may mainly stay at home or in bed, or may suffer relapses throughout their lives.[11]

Mortality[edit | edit source]

One study found no increased risk of all cause mortality or mortality from cancer but an increased risk of suicide. Suicide risk was increased 6.85 compared to the general population.[12] It was based on a cohort that used multiple clinical criteria, including the Oxford criteria.[13] A Spanish study found a suicide risk of 12.75% versus 2.3% in the general population.[14]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Two age peaks in the incidence of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a population-based registry study from Norway 2008-2012

- ↑ Reference needed

- ↑ Emerge Quarterly Journal, AUTUMN 2016 - Vol 36 - No 1, page 14, Mar 2016

- ↑ Falk Hvidberg et al, The Health-Related Quality of Life for Patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis / Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS), PLOS One, 5 Jul 2015.

- ↑ reference needed

- ↑ Beth Unger, CDC grand rounds – references needed

- ↑ Two age peaks in the incidence of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a population-based registry study from Norway 2008-2012

- ↑ http://www.meaction.net/2016/08/30/naviauxs-metabolism-paper-is-about-as-big-as-you-think/

- ↑ Two age peaks in the incidence of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a population-based registry study from Norway 2008-2012

- ↑ http://www.njcfsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/Pregnancy-in-Women-with-ME-CFS.pdf

- ↑ reference needed

- ↑ Mortality of people with chronic fatigue syndrome: a retrospective cohort study in England and Wales from the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust Biomedical Research Centre (SLaM BRC) Clinical Record Interactive Search (CRIS) Register

- ↑ Interpretive jiggery-pokery in The Lancet A tale of a convenience sample with inconvenient serious limitations. Quick Thoughts, a blog by James Coyne, February 16, 2016

- ↑ https://afectadasporlosrecortessanitarios.wordpress.com/2016/05/11/risk-of-suicide-due-to-neglect-amongst-pwme/